Baseball Remains Front of Tuttle's Mind, Close to Retired Coach's Heart

By

Doug Donnelly

Special for MHSAA.com

June 29, 2023

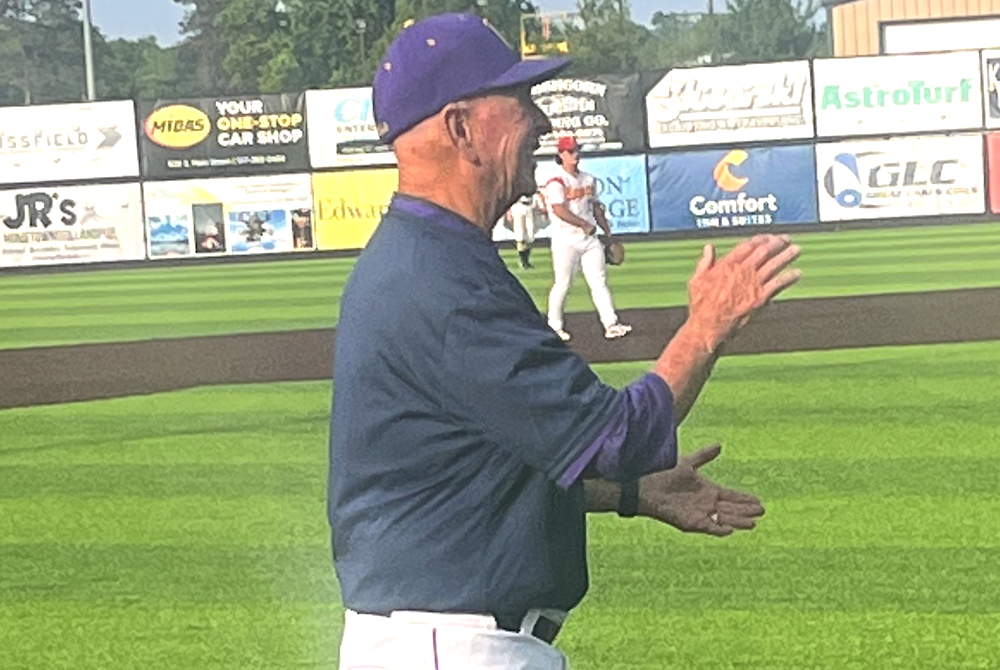

BLISSFIELD – Larry Tuttle jogged out of Tuttle Dugout onto the artificial turf at Adrian College and took his spot in the third base coach’s box, looked in at the batter as he approached the plate and clapped his hands.

It’s like he never left.

For more than 50 years, Tuttle occupied the third base coach’s box for the Blissfield Royals. He is the winningest high school baseball coach in Michigan history and one of the winningest prep baseball coaches in America. It’s been two years since Tuttle last coached the Royals, but when the Lenawee County All-Star Game came around this year, and Onsted coach Matthew Randall was named a head coach of one of the teams, one of his first calls was to Tuttle.

“To see him coach third base again for two innings of that all-star game was nothing short of amazing,” Randall said. “I love that man and everything he has taught me.”

Tuttle and Randall faced off about 40 times over the years.

“There’s a lot of respect between us,” Tuttle said. “I was happy to do it.”

Tuttle, 79, is a Morenci native who played baseball and graduated from Adrian College, coached for one year at Temperance Bedford and five decades at Blissfield. He spends a little more than half of the year in Florida these days in a house he owns in The Villages, a retirement community about an hour north of Orlando.

This past spring, Blissfield took a spring baseball trip to Florida and Tuttle was able to come out to the field and watch a few practices.

“That’s the best time,” he said. “I always enjoyed those first practices of each season. People will ask me, ‘But what about the cold? It’s always so cold in Michigan that first week.’ The first 10 days or two weeks or so inside, that’s where we formed our whole season, working on the fundaments and the strategy, getting the kids mentally ready for the season. That was a fun part of coaching.”

He returns home to Michigan each summer to spend time with his kids and grandchildren, including a freshman-aged granddaughter who is showing good things in softball. His roots are in southeast Michigan, and he has every intention of keeping it that way.

Tuttle’s career at Blissfield was nothing short of remarkable.

Tuttle’s career at Blissfield was nothing short of remarkable.

He coached Blissfield for 54 seasons. It would have been 55, but the 2020 season was canceled due to COVID. The Royals won 1,332 games during his career. They won 33 District titles, 23 Regional championships and seven Finals crowns. Blissfield also won 40 league titles, including in his final season of 2021. His No. 18 jersey was retired by the school district.

In 2015, Tuttle was an easy inaugural choice for the Michigan Baseball Hall of Fame.

This summer, Tuttle returned to Michigan in time to see Blissfield play a few regular-season games and was there when his beloved Royals played in the Division 3 District tournament. He wore his familiar Royals gear. When the Lenawee County All-Star game was played, Tuttle was in his full Blissfield uniform. It still fits perfectly.

“I still enjoy the game,” Tuttle said. “It’s my energy level that just isn’t what it used to be. That’s why I stepped down. I still love the strategy of the game.”

When he’s watching a game, he still goes through every play in his mind and what he would do if he was calling the shots.

“You’re always coaching even though you might a spectator,” he said. “It may not be the right way, but it’s my way. That’s baseball. I love thinking about what to do on this count or that count, to take a pitch or not.

“I see a lot of coaches these days who had played in college. Young coaches coach the college way, but you are dealing with high school kids who may not have a real firm understanding of the game itself. You have to teach high school baseball to college kids. You don’t teach college or pro ball to high school kids.”

Tuttle, who has battled some health issues the last couple of years, misses being in his role as coach.

“I miss the players and the relationships I had with umpires and the other coaches,” he said. “It’s hard to replace that.”

Tuttle is an icon in Lenawee County. When he goes to a game, people gather around him to talk. He still follows the area teams and has a relationship with several coaches and ex-players.

Tuttle enjoyed monumental success at Blissfield. The Royals’ last sub-.500 season was in 1971.

“I know that because I have the records,” Tuttle said. “The closest we came was we were 8-8 one year in the 1980s.”

Tuttle has been a stickler for stats his entire career. Some coaches have a hard time remembering how their team did two years ago. Tuttle knows. He kept intricate stats on every team he’s coached at Blissfield and to this day has them organized only a few steps away from his kitchen table at his home in Blissfield – which is just across the street from the high school and a long home run away from the baseball field that is named in his honor.

“I have a file cabinet full of files from each season and I have the scorebook from every year I coached at Blissfield, starting in 1968,” Tuttle said. “Stats were always important to me, not the wins, but the stats. Baseball stats tell you so much about the game.”

Since stepping aside, Tuttle has had time to reflect on his career.

“I would have never believed I would have coached that long,” Tuttle said. “Then, I sit back and think, ‘That was a lot of wins, wasn’t it?’ I don’t mean that in a bragging way. I think more about it when I go to a game.”

Randall recently announced his retirement from Onsted after 13 years as head coach. Onsted is in the same conference as Blissfield, the Lenawee County Athletic Association, so he had a close-up view of Tuttle in action.

He now has a memory of the last game he coached at the All-Star Game at Adrian College.

“I credit a lot of my coaching philosophy to this day to him,” Randall said. “Our relationship has really grown over the years. I wanted Coach Tuttle to be with me in my final game. That’s why I asked him.”

PHOTOS (Top) Retired Blissfield baseball coach Larry Tuttle coaches third base during the June 26 Lenawee County All-Star Game. (Middle) Tuttle’s jersey is retired during a 2021 ceremony. (Photos by Doug Donnelly.)

St. Francis Adds 4th 'C' to 'Character, Commitment and Compassion' - Championship

By

Dean Holzwarth

Special for MHSAA.com

June 14, 2025

EAST LANSING – Traverse City St. Francis senior Charlie Olivier threw up three fingers before heading to the outfield in the seventh inning of Saturday’s Division 3 Final.

It signified more than the three outs the Gladiators would eventually get to accomplish a feat that hadn’t occurred in 35 years.

“At St. Francis, when we arrived in middle school, there were the three Cs – character, commitment and compassion,” Olivier said after a 5-4 win over Marine City at McLane Stadium.

“And it reminded me of the three outs of the seventh inning, and I held up the three just because all we’ve been doing this year is showing character and commitment to this team and showing so much compassion for one another. I wouldn't want to do this with anyone else other than this team.”

Appearing in a Division 3 Final for the third time over the last eight years, the Gladiators (31-8-1) overcame a late rally by the Mariners to hang on and win their first championship since 1990 (in Class D).

“Winning a state title in baseball is so hard, and there are so many things that can happen to lose one baseball game – and not always does the best team win,” said St. Francis coach Tom Passinault, who’s been coaching high school baseball and football since 1993.

“We’ve had some really good teams through the years that got beat, but this team finally did it and turned the corner and made us state champs.”

The Gladiators struck first in the opening inning when junior Matthew Kane ripped an RBI single to score junior Tyler Thompson, who led off the game with a single.

St. Francis added to its lead with a three-run third inning.

Kane delivered another RBI single to make it 2-0, and then Olivier followed with a suicide squeeze to score Sam Wildfong.

Kane delivered another RBI single to make it 2-0, and then Olivier followed with a suicide squeeze to score Sam Wildfong.

After a pitching change, Braxton Lesinski knocked an RBI single past a drawn-in infield with the bases loaded and St. Francis held a 4-0 advantage.

“That was awesome,” Kane said. “I struggled a little bit in the playoffs, so to start the game out 2-for-2 with some RBIs – that was special,” Kane said. “My hard work paid off so I'm happy, and this team is so special. We didn’t lose a single guy from last year and added a freshman, and it's just a brotherhood. The coaching staff is awesome, and it’s been a full team effort. I couldn't be more proud of these guys.”

Harrison Shepherd’s sacrifice fly in the fourth inning scored Thompson to give St. Francis a 5-0 cushion, but Marine City didn’t go away quietly.

The Mariners, playing in their first Final, scored four runs with two outs in the bottom of the inning, courtesy of a hit batsman, a wild pitch and a throwing error.

“It’s kind of what they always do; they battle all the time,” Marine City coach Ryan Felax said. “We haven't been held under four or five runs the whole tournament, so I knew falling down 5-0 wasn't anything and we would be able to battle back. It just was not enough in the end, and this is a tough one to swallow. It just hurts.”

St. Francis starter Tyler Endres held the Mariners hitless through the first three innings before Lanse Vos replaced him in the fifth.

Vos settled down after the rocky end to the fifth inning and retired six of the last seven batters he faced.

“I felt really good at 5-0, and Tyler was mowing,” Passinault said. “We knew we would go with Lanse at some time, and I put him in a bad spot with coming in on a 2-0 (count), but then he had a couple clean innings.

“I’ve been around high school sports for a long time and always been envious of guys who had 30-year reunions for state championships. I’m just ecstatic.”

PHOTOS (Top) Traverse City St. Francis’ Tyler Thompson (2) eludes a tag at home to score one of his two runs during the Division 3 Final. (Middle) The Gladiators’ Tyler Endres delivers a pitch.