Brighton Memories Close to Henson's Heart

By

Steve Vedder

Special for MHSAA.com

November 7, 2017

Drew Henson admits he'll still sneak an occasional peak at the record book.

After 20 years and professional careers in two sports, a quick glance isn't about vanity for Henson. The former Brighton football and baseball star said he's simply curious whether his myriad records are withstanding the test of time.

"Sometimes somebody will send me (a link), and I'll look to see if anybody is getting close," Henson said. "I've got to see who is coming up."

Henson, 37, graduated from Brighton in 1998 having set 11 major hitting records, eight of which he still holds 20 years later. He's also noted among the state football record setters after throwing for 5,662 yards and 52 touchdowns during his Bulldogs career. Twice he threw for more than 2,000 yards in a season during an era right before spread offenses made doing so a much more regular occurrence. In addition, he was a standout basketball player as well at Brighton and his class’ valedictorian.

In baseball, Henson is still the all-time career leader in hits (257), doubles (68), home runs (70), grand slams (10) and RBI (290). The 70 homers is 23 more than those hit by any other Michigan high school player, including eventual major leaguers such as Nate McLouth (Whitehall), Ryan LaMarre (Jackson Lumen Christi) and Zach Putnam (Ann Arbor Pioneer). Henson drove in at least 78 runs every season sophomore through senior years. He's the state's all-time leader in RBI by 87. He also continues to hold national high school records for career RBI and grand slams.

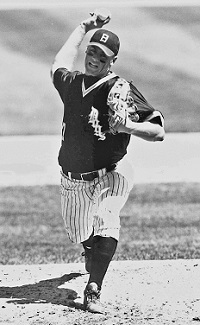

Henson's senior baseball season is unquestionably the best ever amassed by a Michigan prep player. He set single-season records with 22 homers and 83 RBI, batted .605 and went 14-2 as a pitcher, including appearing in an MHSAA tournament game in which he struck out 20 of 21 batters, allowing batters to make contact with a pitch only twice.

Now living in Tampa, Fla., Henson he still views the records the same way he did before he departed to play quarterback at University of Michigan and then eventually sign $3.5 and $17 million contracts with the Dallas Cowboys and New York Yankees, respectively. Henson, who once fielded ground balls beside Derek Jeter and battled Tom Brady for a starting job, played on four Brighton baseball teams that averaged about 30 wins per year.

Now living in Tampa, Fla., Henson he still views the records the same way he did before he departed to play quarterback at University of Michigan and then eventually sign $3.5 and $17 million contracts with the Dallas Cowboys and New York Yankees, respectively. Henson, who once fielded ground balls beside Derek Jeter and battled Tom Brady for a starting job, played on four Brighton baseball teams that averaged about 30 wins per year.

"A lot of factors created those opportunities for me. You don't set records like that without playing on a good team with good teammates," he said.

"We were a good hitting team from one through nine in the order. Our goal was to try and win state every year. I wouldn't have hit the homers or driven in the runs every year without my teammates. I have a lot of vivid memories of high school that are near and dear to my heart."

Former Brighton coach Mark Carrow said it's no surprise to him that Henson still owns the record book two decades after graduating. Carrow said Henson was the perfect blend of work ethic and natural talent.

"I coached for 34 years, and he was without question the best player I ever saw," Carrow said. "From the time he came to us as a freshman, it took one look at him throwing or one look hitting to know he was special.

"If there was a checklist for what you wanted in a baseball or football player, he checked the top of the box every time. He could throw 97, 98 (mph) and he could hit. He could dominate a game."

Carrow said the records are even more remarkable when you consider Henson every season would draw more than 40 walks, many intentional.

"Scouts used to come to the games, and I mean teams' top scouts," Carrow said. "And they'd say Drew was as good as they had ever seen."

Henson’s parents both were Division I college athletes, and his father Dan coached football at four Division I programs. Still, Drew’s dual sport professional career nearly took a different path as a youngster. While Henson started playing T-ball as a 5-year-old, his first love during his preteen years was basketball. Henson didn't play his first competitive football game until the eighth grade.

Considering he had interests in virtually every sport and at least in part because his father was a football coach, Henson thought of himself as a "gym rat" growing up. He would tag along to his father's practices, devour box scores in the paper and prop himself in front of the television on fall afternoons.

Much of high school athletics today is focused on specialization, but Henson said he never considered narrowing his sports to one. In fact, he encourages his young daughter to play as many sports as she can fit in.

"It never got dull for me," he said. "For a lot of kids today, it's too much for too long. You don't get a mental break. You can start to lose you."

While Henson's high school career was one for the record books, and he helped the Wolverines to a 9-3 record and Cotton Bowl win in 2000, his professional career never took off. He was a third-round draft pick by the Yankees (97th overall) in 1998 and sixth-round pick of the NFL's Houston Texans in 2003.

While Henson's high school career was one for the record books, and he helped the Wolverines to a 9-3 record and Cotton Bowl win in 2000, his professional career never took off. He was a third-round draft pick by the Yankees (97th overall) in 1998 and sixth-round pick of the NFL's Houston Texans in 2003.

He stalled at Triple-A in the Yankees system, but did make the major leagues in 2003, singling off the Orioles' Eric DeBose for his only big league hit. He wound up retiring from baseball following the season after hitting .248 with 67 homers and 274 RBI in 501 minor league games. He was 23 years old.

In the NFL, Henson wound up making one start for the Cowboys in 2004 and in 2008 joined the Lions for a season. Henson threw one touchdown pass as a Cowboy, to Jeff Robinson in 2004.

Henson, who in July of 2015 still rated a profile in Sports Illustrated a decade after throwing his final pass in the NFL, has been asked many times about his lack of success in professional sports. Past speculation states he was rushed through the Yankees' chain, while participation in professional baseball may have stunted his football development.

Two decades after leaving Brighton, Henson said he still answers the question of which sport was actually his favorite the same way: with diplomacy.

"I've always said nothing was more fun than to play baseball, but there is also nothing like being in the huddle on the football field," he said. "It's hard to say which I liked more. You can play baseball every day, but you can only play football once a week."

The one regret Henson may harbor has to do with patience. If he had to do it all over again, Henson said he'd force himself to slow down and enjoy the process. Henson said he often felt he had to play catch-up in both sports.

"I would tell my younger self to have more patience. There were so many opportunities after my junior year (of college) that would have still been there as a senior," he said. "Because of that I wish I would've had more patience and let the process play out."

Henson said his message to youngsters who face the same challenge is simple.

"Society is so go, go, go," he said. "You just have to learn to hit the pause button. If you're always on to the next thing, you're not embracing the moment. I wish I had done more of that.

"If you like to work and put in the time, you can be successful. All that goes into it. If you have the heart and desire and pay attention to detail, you will be successful."

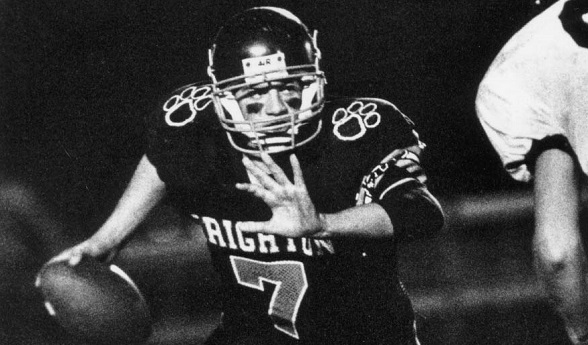

PHOTOS: (Top) Drew Henson starred during the fall at Brighton’s quarterback. (Middle) Henson struck out 20 of 21 batters he faced in a 1997 game against Walled Lake Western. (Below) Henson also was a basketball standout, averaging 22 points per game according to a Sports Illustrated profile published in 1998. (Football and basketball photos courtesy of Brighton High School).

Sontag Inspires Amid 'Miracle' Cancer Fight

January 3, 2020

By Doug Donnelly

Special for Second Half

PINCKNEY – Dave Sontag could tell something was wrong.

The gymnasium at Petersburg-Summerfield High School is bigger than most in Monroe County. But when Sontag, a veteran official, was running up and down the floor, he felt unusually tired and began feeling pain in his back.

The gymnasium at Petersburg-Summerfield High School is bigger than most in Monroe County. But when Sontag, a veteran official, was running up and down the floor, he felt unusually tired and began feeling pain in his back.

“I knew something was wrong,” Sontag said. “During a timeout, I told one of the other officials who was in the stands watching that he might have to finish the game.”

Sontag, however, pushed through and made it.

“That’s when it all began,” he said.

A few weeks later, as the Saline varsity baseball coach, Sontag was hitting fly balls to the Hornets’ outfielders.

“I was struggling,” he said. “I called the players in and told them something was wrong. I had to stop.”

Still trying to fight through whatever was wrong, Sontag was coaching third base during a Saline intra-squad scrimmage a short time later.

“I started to see white,” he said.

He had another member of the Saline coaching staff call his wife, Michelle, who came and picked him up and took him to the hospital in Chelsea.

“My blood counts were trash, just trash,” he said. “The doctors said I need to have a blood transfusion.”

He was rushed to a Detroit-area hospital for the transfusion. After tests, Sontag was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, an extremely vigorous, aggressive cancer. That was May 15, 2018.

During the 18 months since, Sontag has gone through chemotherapy and radiation treatments. He’s watched multiple communities respond with fundraisers and benefits and amazing support. He’s had more than one bone marrow transplant. He’s heard from countless friends and ex-players who have continued to lift his spirits day after day via e-mails and text messages. He’s been counted out more than once.

Yet, he’s survived.

“Every day has been a challenge,” he said.

***

Sports and Sontag have gone together from the beginning.

He is a Monroe County native who was The Monroe Evening News Player of the Year in baseball in 1978 and went on to play at the University of Toledo. He taught journalism and English at his alma mater, Monroe Jefferson, before becoming a counselor for another 12 years. He was also the Jefferson director of athletics and recreation for a time.

He coached baseball for the Bears, leading the team to nearly 400 victories and the Division 2 championship in 2002. He stepped down from coaching to follow his kids, who were playing at higher levels; Ryan Sontag played at Arizona State University and in the Chicago Cubs organization. Susan played softball at Bowling Green State University, and Brendan played ball at Indiana Tech University.

He coached baseball for the Bears, leading the team to nearly 400 victories and the Division 2 championship in 2002. He stepped down from coaching to follow his kids, who were playing at higher levels; Ryan Sontag played at Arizona State University and in the Chicago Cubs organization. Susan played softball at Bowling Green State University, and Brendan played ball at Indiana Tech University.

Still, the desire to coach never left their dad.

“After my kids were done playing, I coached freshman baseball at Jefferson,” he said. “I missed it and still wanted to be part of it.”

With his wife a principal in the Saline district, Sontag was asked by Scott Theisen, Saline’s head coach, to join his staff in 2015. He was with the Hornets when they captured the Division 1 championship in 2017, then was named head coach before the 2018 season started.

“That was the year I got sick,” he said. “I didn’t even finish the year.”

Sontag also has been a basketball official for years, getting his start in the early 1980s. He’s been a registered MHSAA high school basketball official for 40 years and has trained officials for the Monroe County Basketball Officials’ Association. He’s called four MHSAA Finals championship games.

“My first varsity game ever was when I was 21,” Sontag said. “I refereed a game at Whiteford.”

***

Sontag previously battled non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1995-1996, beating that disease after a nine-month battle.

Although this cancer battle began as he was new to the Saline community, they embraced his fight, selling “Team Tags” T-shirts and painting the youth baseball diamond with a big ribbon. His son, Ryan, was invited to throw out the first pitch before the youth baseball season started in Dave’s honor.

Back home, in Monroe County, Sontag’s school held similar fundraisers and blood drives.

“I had so much support,” he said. “It was quite amazing to see.”

He tried all sorts of treatments, ultimately boarding an airplane and heading to Seattle for a clinical trial. It didn’t work.

“At that point, I didn’t think I was going to live,” Sontag said. “They told me there was nothing more they could do. They just were giving me something to take the pain away. I was miserable.”

Still, Sontag said, he held out hope.

“I felt it wasn’t time yet,” he said. “I have three grandkids. There are things I want to do. There’s so much I haven’t accomplished yet. In Seattle, they didn’t count on me living.”

But, for a still-unexplained reason, a combination of the medicine he was given to “take the pain away,” on his flight home and a different medicine he received when he returned to Michigan, started to change the way he felt. His blood counts started getting better.

“The side effects were lousy, but, for some reason, it threw me into remission. They checked for leukemia and it was not there.

“We called it a miracle.”

***

Sontag, who lives in Pinckney now, is still dealing with the side effects of nearly two years of treatments. He has a tingling sensation in his arms and legs – the feeling people get when their hands or feet ‘fall asleep’ – and he has a weak immune system.

But he gets a little better every day.

But he gets a little better every day.

“Every day is a blessing,” he said.

In addition to the community support and constant praying, he credits his wife with guiding him through this process.

“Michelle has been a rock through all of this,” he said. “She’s been by my side every single day. Without her, I don’t know if I would have made it.”

Recently, the Monroe County Officials’ Association held a banquet during which Sontag was presented with a “Courage Award.” He isn’t sure if he’ll be able to referee again anytime soon.

“I told them that night that I’d like to do it again, somewhere,” he said. “I don’t care of it’s a seventh-grade game. I just want to get out there again.”

In addition to the outpouring of love from multiple communities, family and friends, Sontag said sports has kept him alive.

“Sports is part of my fabric,” he said. “Baseball and officiating basketball games has given me that motivation I’ve needed to fight through this. I don’t know if I will coach again or referee again. I’m definitely not going to jump into the same schedule. But there are things I would like to do.

“Will I become a head coach again? Probably not. The task of being a head coach is probably too big right now. But I’d like to be involved. I’d still like to run camps and clinics. I’d still like to officiate too. I want to be a part of it. It’s something that’s in my blood.”

His son Ryan lives in Saline and has three children. Ryan coaches his son in a youth baseball league.

“He called me the other day and asked if I’d help him out,” Dave Sontag said. “I told him I think he will get me out there at some point.”

Doug Donnelly has served as a sports and news reporter and city editor over 25 years, writing for the Daily Chief-Union in Upper Sandusky, Ohio from 1992-1995, the Monroe Evening News from 1995-2012 and the Adrian Daily Telegram since 2013. He's also written a book on high school basketball in Monroe County and compiles record books for various schools in southeast Michigan. E-mail him at [email protected] with story ideas for Jackson, Washtenaw, Hillsdale, Lenawee and Monroe counties.

Doug Donnelly has served as a sports and news reporter and city editor over 25 years, writing for the Daily Chief-Union in Upper Sandusky, Ohio from 1992-1995, the Monroe Evening News from 1995-2012 and the Adrian Daily Telegram since 2013. He's also written a book on high school basketball in Monroe County and compiles record books for various schools in southeast Michigan. E-mail him at [email protected] with story ideas for Jackson, Washtenaw, Hillsdale, Lenawee and Monroe counties.

PHOTOS: Longtime official and coach Dave Sontag – standing in front row with wife Michelle, daughter-in-law Amy and son Brendan – is presented a “Courage Award” by the Monroe County Officials Association. (Middle) Sontag, formerly baseball coach at Monroe Jefferson and Saline, mans his spot on the baseline. (Below) Sontag with officials, from left, Mike Gaynier, Mike Bitz, Mike Knabusch and Dan Jukuri. (Top and below photos courtesy of Knabusch; middle photo courtesy of the Monroe News.)