Coach Comes Home to Lead Central's Rise

By

Tom Markowski

Special for Second Half

September 27, 2017

DETROIT – Thirty-three years ago, Lynn Sanders graduated from Detroit Central. And before he left, he made a promise.

Last year, Sanders showed he is a man of his word.

Last year, Sanders showed he is a man of his word.

Sanders, 51, is in his second season as the head football coach at Central. Once a proud program under legendary coach Woody Thomas (who died in 2002), the program had wavered a bit. Coaches like Michael Thornhill, who took over for Thomas in 2002, Eric Smith, Robert Hunt and others have had some success. But stability within the program, especially in recent years, had been missing.

Many of the high school-age students in the neighborhood were attending schools elsewhere in the city. Now-closed Detroit Allen Academy, a charter school near Central, was one alternative. Open enrollment throughout the school district also allowed students to attend any school in Detroit, and many were taking advantage of the opportunity.

Since Sanders’ arrival, and because of his standing in the community, many of those in the neighborhood have decided to remain. Sanders and his staff have been able to make the Trailblazers relevant again, and there’s a renewed respect for the program. Central is 4-1 and 2-1 in the Detroit Public School League Black division and faces Detroit Pershing (1-4, 0-3) this week before taking on Detroit Martin Luther King (4-1, 3-0), one of the state’s elite programs, on Oct. 6.

“When I was 18, I told Coach Thomas I would replace him,” Sanders said. “It took a while.”

The rewards have come quickly.

Last fall in Sanders’ debut, and for the second time in school history, the Trailblazers won two playoff games in a season and finished 7-5. And they led Millington 20-0 in a Division 6 Regional Final before falling 22-20.

There had been success in the recent past. Central tied a school record for victories in a season with a 9-3 finish in 2010. In 2012, the Trailblazers began a run of making the playoffs in three of the next five years, each time finishing 6-4 – although the playoff appearances in 2014 and 2015 ended quickly as Central lost first-round games by a combined score of 107-14.

There had been success in the recent past. Central tied a school record for victories in a season with a 9-3 finish in 2010. In 2012, the Trailblazers began a run of making the playoffs in three of the next five years, each time finishing 6-4 – although the playoff appearances in 2014 and 2015 ended quickly as Central lost first-round games by a combined score of 107-14.

The Trailblazers took a sizable next step led by someone taking his first at the high school level. Sanders had never been a head coach, but he brought a long list of credentials while working with youth football. A 27-year veteran with the Michigan State Police, Sanders spent 10 years as the president of the Southfield Ravens, a Pop Warner program for players aged 8-11. He spent three years as a league commissioner within Pop Warner in southeastern Michigan. For two years he was a regional commissioner for American Youth Football (AYF).

Before getting the Central job, Sanders worked under coach Keith Stephens at Oak Park and then with Stephens at Southfield-Lathrup as his offensive coordinator.

Then there was a knock on the door of opportunity.

“I got a call from David Oclander, who was the (Central) principal then,” Sanders said. “We met and he told me what he was looking for. He knew of me, knew I was a Central grad, and he told me he wanted to turn things around.

“When I got here the team GPA was 1.9. The first day I called a meeting. I had all of the guys who wanted to play be there. When I gave that speech, I could tell they weren’t really happy. I was their third coach in three years, and I think they felt betrayed. They weren’t really interested. A number of them were looking at their phones, not paying attention. I told them here are my rules, my expectations and if you don’t like it you can leave. About half of them did. Fifteen stayed.”

It didn’t take long for Sanders to build upon those numbers. His association with Pop Warner and coaches in the area helped spread the word that expectations would rise.

In the meantime, Allen Academy closed following the 2015-16 school year and many of those students went to Central – including some athletes who had played on a Wildcats team that finished 5-4 in 2015.

Central didn’t have a freshmen or junior varsity team, but Sanders was able to gather 36 for the varsity. He has 32 this season.

Central didn’t have a freshmen or junior varsity team, but Sanders was able to gather 36 for the varsity. He has 32 this season.

“When I took the job I got phone calls from all over the place,” he said. “Coaches, former players, they all wanted to help. They’d do anything for me. I was well-respected, and the kids started to come. Instead of taking buses out of the neighborhood and going elsewhere, they stayed home. And they were good kids. I set some high expectations. Those that didn’t want to follow got shipped out.”

Sanders and Oclander saw eye-to-eye on many issues. The main objective was to instill discipline, and both came from a background where discipline was paramount: Sanders with the state police, Oclander as a retired lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army.

Sanders looked to improve the quality of coaching his players were to receive in two ways. The first came during the offseason. He knew his players didn’t have the finances to go to camps, even if they were close by at places like Wayne State University. Instead, Sanders brought the college coaches to Central. Staffs from Northwood University, Eastern Michigan and Wayne State all came to Central to conduct a camp.

“That had never been done before at Central,” Sanders said.

The second was to convince coaches in the area that Central was the place to be. Eighteen said yes. Do the math: That’s more than one coach for every two players. It’s safe to say that’s a unique situation – and has led to an almost unheard of type of mentoring process.

And the players are reaping the results. Eight players from last year’s team are playing college football. Five players from this year’s team have made verbal commitments to a college or university, including El Julian Jordan. Jordan, a 6-foot-2, 220-pound quarterback who played his first two years of high school football at King, has accepted a scholarship to Western Michigan.

It was a big change for Jordan to go from a program like King, with 1,400 students, to Central where the enrollment is 370.

“It was a tough transition,” he said. “The kids in school were different. This school is so small, but I like it that way. I can focus more on my grades and such.

“I look up to (Sanders). He’s molded me into a leader. I lead by example. My first impression of Coach was a positive one, and that’s good.”

Jordan has had a fine season to this point, completing 56 of 95 attempts for 1,239 yards, 13 touchdowns and with no interceptions. He’s scored three rushing touchdowns.

“He’s a special kid,” Sanders said. “I don’t think anyone has put him in the position of being a leader before. After time, he knew he could trust me. He’s a phenomenal athlete. He’s a quiet kid until you get to know him. As we made our run in the (playoffs), the different (officiating) crews would watch him warm up. He can throw the ball 70 yards. And they couldn’t wait to see him in action.”

“He’s a special kid,” Sanders said. “I don’t think anyone has put him in the position of being a leader before. After time, he knew he could trust me. He’s a phenomenal athlete. He’s a quiet kid until you get to know him. As we made our run in the (playoffs), the different (officiating) crews would watch him warm up. He can throw the ball 70 yards. And they couldn’t wait to see him in action.”

Other top players include a bevy of receivers including Jerodd Vines, TaQuan Snead and Brandon Cooper.

Central returned all five offensive linemen from a season ago including Jamauri’a Carter (5-10, 305). Carter, Snead and Jordan all played on the Eastside Raiders in the Police Athletic League (PAL) before high school.

Sanders’ stay at Central could be a brief one. He and wife, Kathy, who were high school sweethearts, have four children including three sons. One, Londale Sanders, is a junior linebacker at University of Arkansas-Pine Bluff. They recently returned on Sunday after watching their son play in last Saturday’s 34-27 overtime victory at Jackson State.

Another son, Lance Sanders, is one of the offensive line coaches at Central.

“I don’t know how long I’ll do it,” Lynn Sanders said. “I wanted to turn things around. I don’t know how long I’ll be here. I told my wife three years, tops, and see what happens. At least Central is back where parents, the people in the neighborhood are coming back. The kids are getting better. The test will be against King.”

Tom Markowski is a columnist and directs website coverage for the State Champs! Sports Network. He previously covered primarily high school sports for the The Detroit News from 1984-2014, focusing on the Detroit area and contributing to statewide coverage of football and basketball. Contact him at [email protected] with story ideas for Oakland, Macomb and Wayne counties.

Tom Markowski is a columnist and directs website coverage for the State Champs! Sports Network. He previously covered primarily high school sports for the The Detroit News from 1984-2014, focusing on the Detroit area and contributing to statewide coverage of football and basketball. Contact him at [email protected] with story ideas for Oakland, Macomb and Wayne counties.

PHOTOS: (Top) Detroit Central quarterback El Julian Jordan warms up before a game. (Middle top) Lynn Sanders, left, and offensive coordinator Kevin Rogers. (Middle below) Jordan surveys the field looking for a receiver. (Below) Sanders and wife Kathy. (Photos courtesy of Lynn Sanders and Detroit Central football.)

Culmination of Ideas, Cooperation Lead to Creation of MHSAA Football Playoffs

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

August 26, 2022

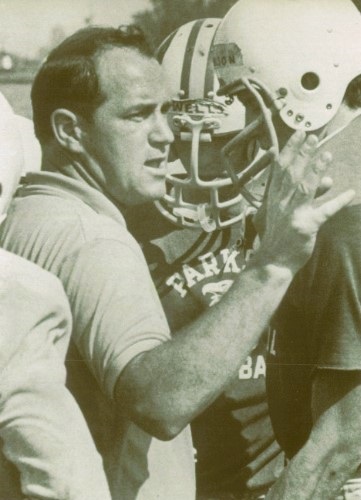

In November of 1972, Dave Driscoll, football coach at Jackson Parkside, was talking by phone with Larry Paladino of The Associated Press about the goals of the recently-formed Michigan High School Football Coaches Association (MHSFCA).

“Football has been around a long time in Michigan, and we just haven’t moved forward as other sports have. Now with an organization to speak and help us, I think we will see some real movement …”

Driscoll, president of the MHSFCA, was pitching the idea of a football postseason in Michigan – a goal of the young organization.

“It took us a couple of years to get it done,” recalled Driscoll, now age 86 and still in the Jackson area. “The first year or two was a challenge because that’s when you’re instituting something. But it has turned out to be a very progressive, positive influence in the state.”

A Postseason

Michigan was one of only 20 states that did not conduct a football playoff, and the sport was the only one sponsored by the MHSAA that did not have a tournament to determine champions. Newspaper ranking systems, in use since the early 1940s in Michigan, were the method by which football teams were awarded “state titles.” Prior to that, schools with undefeated marks against in-state opponents could make a rightful claim to a championship. Because there was no postseason system in place for teams to square off, those are referred to as “mythical” titles.

A state gridiron playoff had been discussed for many years. But, as a cold weather state, few could see a way to devise an equitable system to accomplish the task. With basketball, every high school squad qualified for the annual MHSAA Tournament. Logistically and geographically, the concept of a football postseason presented numerous challenges. Unpredictable late fall weather meant the season could be expanded by only a couple of weeks. That limited the number of teams that could be involved.

Yet Colorado and Massachusetts, both with weather that could replicate Michigan’s in late autumn, hosted football postseasons.

Yet Colorado and Massachusetts, both with weather that could replicate Michigan’s in late autumn, hosted football postseasons.

“They just extend the season by two weeks,” said Driscoll, the MHSFCA spokesperson at the time. “They divide the state by regions. If you win a region, you have a semifinal game the next week, then a final a week after that in each class.”

The MHSFCA, broken into 18 regions across the Upper and Lower Peninsulas, recognized that was far too many to work within a two-week playoff system. So, determining the teams that would participate in the tournament was a major concern.

“Ohio rates its teams by computer. Pennsylvania has a system for it. … Our association would have to investigate these and come up with the best one for our situation,” Driscoll said.

Only eight months old, the MHSFCA planned to present its research, and a possible approach, to the Michigan High School Athletic Association. Driscoll had spoken to both Allen W. Bush, MHSAA executive director, and Vern Norris, associate director, about the goal.

“They’re listening,” he told the press. “If we can come up with a feasible plan, I think they’re willing to listen. We hope to have playoffs in two or three years.”

So the MHSFCA went to work, scheduling meetings around the state – talking with, and listening to, membership.

“We’re not going to press for any certain system at this time. It will take time to work out the details. We just want to sell the idea,” Driscoll said.

The MHSFCA recognized it could take a while.

“Iowa had to present the playoff five years before it was approved,” noted Driscoll.

While the administrative wheels turned, the MHSFCA worked on developing a point system designed to reward teams based on strength of schedule. The goal was to create a test – ideally during the 1973 season – designed to prove the concept, with the hope for an actual playoff in the fall of 1974.

One thing almost certain to occur, if a system could be developed, would be a recasting of those newspaper rankings.

“Indiana had a dry run on their (proposed) playoffs last year and four of the top five teams in the football polls did not make the playoffs on a point system.”

“No matter how honestly polls are conducted,” stated Jim DeLand of the Benton Harbor Herald-Palladium in April 1973, “they inevitably favor unbeaten teams with an easier schedule over teams with a tougher schedule, and say, one loss.”

Financing the Idea

According to the coaches’ group, most football playoffs in other states had been self-supporting and profitable. “Ohio played its semifinals in a doubleheader at the Ohio State stadium last fall and drew 20-some thousand people,” noted Ike Muhlenkamp, coach at St. Joseph High School and Region 5 director of the MHSFCA, in conversation with DeLand. That additional revenue, he noted, could be used to support other things that were coming along, like girls athletics.

MHSFCA regional directors conducted meetings around the state in April 1973 to explain the proposal.

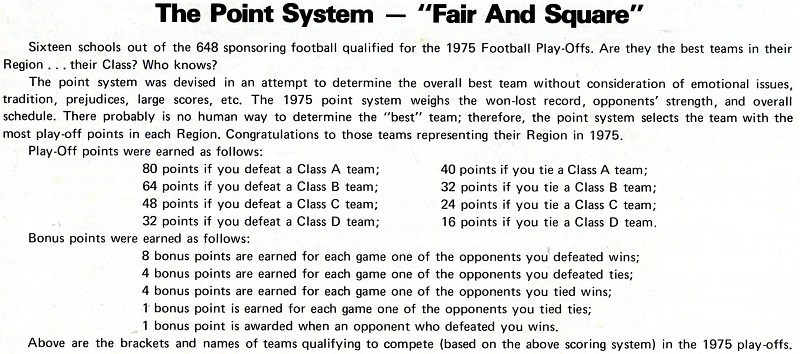

The idea was to use a point system to determine which teams would qualify for play. A school’s classification – Class A, B, C, or D – determined by enrollment size, would be used here as well. Just like basketball, four schools would emerge as champions at the end of the tournament.

“It’s complicated … complicated,” said Bush about the proposal to institute a football playoff just prior to a May pitch by the coaches to the MHSAA Representative Council. “There’s a tremendous mass of bookkeeping involved. Other states are doing it, and we can’t turn our backs on it, but I don’t anticipate it happening this year.”

The Council was receptive to the idea, but it needed examination and testing. The Council called for the assembly of a “Blue-Ribbon panel” of superintendents, principals, athletic directors and coaches from around the state to determine the potential of a football postseason and to explore and address the challenges. Harley Pierce, Sturgis football coach, was named chairman of the committee.

“We’d like to see it operate on paper first,” Driscoll told Dean Howe of the Flint Journal. “That way, we’d know approximately how the real thing would operate.”

“Right now, the Blue-Ribbon committee is studying three point systems, ones used in Ohio, Virginia, and Iowa,” noted Howe. “In Ohio, ratings are done strictly by computer. It costs $5,000 a season to use the computer system.”

In October, the Council asked that the proposed point system be refined.

A key component, as envisioned by the MHSFCA, was to create a system that factored in the quality of competition played by a team during the regular season.

“A team with an 8-1 record might be picked over a 9-0 club by season’s end if that team had played much better competition,” explained Howe.

A special questionnaire was distributed by the MHSAA in February 1974. “By almost a 5 to 1 margin, prep coaches throughout the state supported the playoff,” stated Bob Gross in the Lansing State Journal.

Under the refined system, football game results would be gathered and run through a formula that awarded points based on wins and ties constructed around enrollment classifications, and bonus points for the results of games played by your opponents. League affiliation and margin of victory held no bearing on playoff points awarded.

Under the refined system, football game results would be gathered and run through a formula that awarded points based on wins and ties constructed around enrollment classifications, and bonus points for the results of games played by your opponents. League affiliation and margin of victory held no bearing on playoff points awarded.

In May, the Representative Council, acting on the strong support by coaches for a football tournament, instructed staff at the MHSAA to conduct a sample playoff, on paper, during the 1974 season. The approach would serve as a testing ground – a place to run the idea around the track with live data.

The reality of an actual postseason was still, at minimum, a year away. If all worked as intended, the hope was for an actual tournament in 1975 and 1976, with a re-evaluation of the system to follow. But obstacles remained.

“Weather, playing conditions, sites, records of teams and you name it, we’re faced with just about everything when it comes to something like this,” said Bush. “Teams in the U.P. start the regular season two weeks early so naturally they’re finished by the time teams in the Lower Peninsula are in their sixth and seventh games.” If a U.P. team qualified for the proposed tournament, “they’d have to wait two weeks at least to prepare for a playoff.”

In the end, the idea would still need approval by the Association of Secondary School Principals, which had the “final word on all athletic policies.”

“The coaches are on one side of the fence and administrators (on) the other,” Bush continued. “(T)here’s still a lot of work to do before we actually have a playoff.”

Paper and Pencil

University of Michigan’s Bo Schembechler endorsed the idea and stated in a letter to the MHSFCA that he’d like to see the title game played at U-M. Within, he addressed a concern expressed in some administrative circles. At the time, 652 schools in Michigan played football.

“The fact is that only 16 schools will have an extended season,” stated Schembechler. “There should be little, if any, effect on the basic philosophy of scholastic emphasis.”

Michigan State football coach Denny Stolz also wrote a letter to the group stating he, too, favored the playoff system.

Labeled the “Paper Playoffs,” the proof of concept was handled in the old-fashioned manner, as according to Bush, a computer would not be used for point calculations. It would cost too much.

Instead, at schools that believed they deserved consideration, athletic directors were to fill out a rating form after the season’s sixth game with appropriate information about the results of games played. School principals were to sign the form and mail it to the MHSAA. A single MHSAA staff member each week would then manually “tabulate the results and determine the top teams in each class of four regions” and release them for publication.

The resulting rank of teams was expected to be controversial by both the MHSAA and the MHSFCA. Smaller schools beating teams above their enrollment classification would benefit from the system. Larger schools facing smaller schools would receive fewer points for a win than they would by defeating a team within their own classification. As predicted, an undefeated season was no guarantee of a place within the 16-team field of qualifiers.

“After the formula was devised, the coaches applied it to the top teams in the 1973 Class A poll,” stated Dave Matthews in a State Journal article that appeared just prior to the start of the 1974 season. Saginaw Arthur Hill – undefeated, untied, and unscored upon across nine games – had been named state champion in every state newspaper poll. The Lumberjacks had outscored their opponents, 443-0, but would have finished third in their region in the playoff rankings behind both Flint Southwestern (8-1) and East Lansing (9-0). Simply put, Arthur Hill would not have qualified for the playoffs. Based on the formula, both Southwestern and East Lansing had played more challenging schedules than Arthur Hill.

Controversy

Results needed for the first tabulation following the Week 6 games were slow in arriving. As of the Tuesday following the game, the MHSAA had received only 60 forms. With Wednesday as the cutoff date, the first round of calculations didn’t include teams – like undefeated South Haven – that appeared in the weekly newspaper polls. (South Haven’s form didn’t arrive until after the deadline). That illustrated the need for timely reporting.

Comparisons between the press polls and the “paper playoff” rankings were common, and by season’s end, they illustrated the seismic shift that was approaching – and a call for action.

“Football games aren’t won or lost on paper. Neither are state championships,” wrote Roger Neumann in the State Journal in early November as the season headed for its conclusion. “That’s why most mid-Michigan prep coaches are anxious to see the state’s experimental ‘paper playoffs’ taken a step further and put on the gridiron.”

While it appeared a large majority of coaches – and school administrators – favored moving forward, support for the proposed system certainly wasn’t unanimous.

East Lansing coach Jeff Smith questioned the approach.

‘I’m still for a playoff,’ Smith told Neumann. ‘‘But I have some reservations. I’m not sure that the No. 1 team in each region is the best team.” While Smith admitted he didn’t have an answer on how to improve upon the suggested point system in place, he offered a suggestion.

“If we’re going to do this, I think we should do it right and have eight teams in the playoffs (per classification). Eight teams would be more representative. You’d still be going with the elite of the state.”

Smith noted an expanded playoff with three rounds could still be accomplished within two weeks as the MHSAA allowed teams to play every five days.

“With or without such a change, however, Smith said he’d vote for a true playoff, adding, ‘Any playoff is better than no playoff at all. Once you’ve got it, you can always make changes later,” reported Neumann.

The final AP polls, released Tuesday, Nov. 12, showed Birmingham Brother Rice, Muskegon Catholic Central, Hudson, and Traverse City St. Francis as respective state champions in Classes A, B, C, and D, respectively. United Press International (UPI) differed in only Class C, with Battle Creek St. Philip as the top-ranked team, just five points ahead of Hudson.

According to the final “paper playoff” rankings, only Muskegon Catholic and St. Philip would have qualified for postseason play.

Approved

“It’ll be the principals who’ll really decide if there’ll be playoffs,” said Dick Comar, publicity director for the MHSFCA in late January of 1975. The principals were to receive a questionnaire within a week asking their opinion on the proposal. They had until Feb. 24 to cast their vote.

The results of the survey would be presented to the MHSAA Representative Council at its March 21 meeting in Ann Arbor (coinciding with the annual basketball championships at U-M’s Crisler Arena), with a final decision concerning the issue “at that meeting or at their meeting in May.”

On March 22, Bush announced the proposal had passed, indicating that 73 percent of high schools that had responded to the survey had voted in favor of postseason play. Michigan would have a football tournament. Sites and dates were to be determined. The Council requested that semifinal games be played on high school fields, and that, if possible, the final-round contests be played on artificial turf.

By May, the MHSAA had contracted ESR Corporation, a data processing firm in Lansing, to handle the input of weekly game results. Using the same formula developed and tested, ESR would be responsible for calculating point totals to determine the state’s best teams by Class and region.

Norris called the plan “a combination of the best features already in use in Ohio, Iowa, and West Virginia.” He credited former Alpena coach Art Gillespie with doing much of the work for “carrying the ball through the preparation stages.”

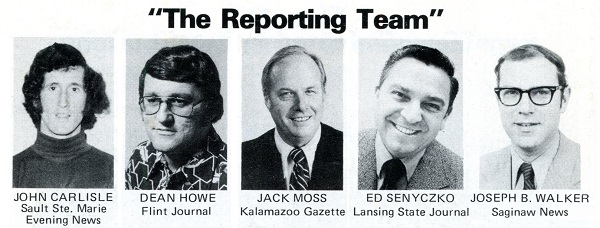

Five members of the media – Howe of the Flint Journal, Jack Moss of the Kalamazoo Gazette, Joe Walker of the Saginaw News, Ed Senyczko of the State Journal, and John Carlisle of the Sault Ste. Marie Evening News – were tasked with capturing the results of games played by 679 schools, including 28 from outside of Michigan, and mailing the results to the MHSAA.

“We’re not interested in the score,” said Bush. “We want to know if a team won, lost, tied, or did not play.”

In August, the MHSAA announced that state title games would be played at two sites on Saturday, Nov. 22. Western Michigan University would host the Class A and D games, while Class B and C were slated for Central Michigan University.

In August, the MHSAA announced that state title games would be played at two sites on Saturday, Nov. 22. Western Michigan University would host the Class A and D games, while Class B and C were slated for Central Michigan University.

The four regions used to divide up the state for the annual basketball tournament also were used as the regions for football.

In September, with the results of the season’s first games – played by the state’s Upper Peninsula teams – fed into ESR’s computers, Bush was clear that the final playoff rankings would cause controversy.

“It’s not necessarily the four best teams in the state that will compete in the semifinals,” he said, “but the best in each region.”

The result was both popular and controversial. The papers continued their weekly football polls. The first MHSAA rankings were not released until Oct 8.

UPI was unimpressed: “If the playoffs were held this weekend – which they are not – not a single one of the teams UPI has rated first in the four classes would qualify.”

Hal Schram of the Detroit Free Press expressed a similar emotion.

“The first computerized points were announced last week and there were glaring differences between the media polls and the MHSAA system,” he wrote.

“’There is no reason to attempt a state football championship, and extend the season two more weeks, when you’re inviting only four teams in each class to perform,’ said Joe Vanderhof, veteran sportswriter of the Grand Rapids Press.

Skepticism continued as the weeks went on, culminating in joy for 16 schools – but disappointment for many others – when the final MHSAA rankings were released Nov. 9.

Norway, undefeated in nine games, was the first to experience heartbreak, as U.P. teams finished their season earlier than others. Tied with Ishpeming in the Region 4 Class C rankings, the Knights lost the playoff spot by a tie-breaking formula. Since the two schools had not played each other, a second method was employed to break the deadlock. The summed win-loss percentage of each school’s opponents was compared, with Ishpeming coming out two-tenths of a percent higher. Two of Norway’s top challengers had not played a ninth game. If either had at least tied another contest, Norway would have slipped ahead in the rankings.

“We’ve been ranked … in the AP ahead of Ishpeming all year,” stated Knights coach Bob Giannunzio. “This is hard to swallow.”

Jim Crowley, coach of Jackson Lumen Christi, was also among the disappointed: “You do everything you can and still don’t make it. Undefeated, the team finished No. 1 in Class B according to UPI.”

“But had it not been Lumen Christi,” noted UPI writer Richard Shook, “then it would have been Dearborn Divine Child (missing out). They were both in the same playoff region.”

Trenton in Class A, Divine Child in Class B, Hudson in Class C and North Adams in Class D finished on top in the final AP poll. Only Trenton did not qualify for the postseason. Traverse City topped Trenton in the final UPI and Free Press polls and did qualify. Lumen Christi finished No. 1 in Class B, Hudson in Class C, and Crystal Falls Forest Park – another qualifier – finished on top in Class D in the Free Press.

“I’ve got the best football team in the state,” Trenton coach Jack Castignola told Schram. “I’ve got at least two future Big Ten players. We had three goals at the opening of practice in August, to go unbeaten, win the conference and the state. We’ve been deprived of reaching our final goal and there’s nothing we can do about it. Corrections are going to have to be made in future years.”

Flint Ainsworth, with a 7-2-0 record, ranked 14th in the UPI poll, was the only team unranked and without even honorable mention in the AP poll to qualify for the tournament.

Livonia Franklin, Divine Child, Ishpeming, and Forest Park emerged as the MHSAA’s first gridiron champions. Since that time, various alterations have been made to the football playoffs. Seasons now begin sooner, many more teams qualify for the postseason, and, beginning in 1976, championship games were moved indoors. Today, 10 teams – eight 11-player squads and two 8-player teams – will be awarded titles come November.

But it was the efforts and collaboration of many that got us here.

“There were a lot of great people involved,” said Driscoll, reflecting on those efforts some 50 years later, and emphasizing that he was only one of many individuals on the same team, uniting behind a goal. “We got great cooperation. We had some super coaches and … some administrators that were not afraid to step forward and say, ‘Hey! These are good people and I know if they do it, they’ll do it the right way.’”

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS (Top) The MHSAA program greets fans for the first Football Finals. (2) Jackson Parkside coach Dave Driscoll talks with one of his players in 1971. (3) A points system was created to determine the field for the first MHSAA Football Playoffs in 1975. (4) Media members were responsible for collecting scores for the MHSAA to tabulate playoff rankings. (Photos gathered by Ron Pesch.)