Flashback: Midland Makes '68 Title Play

August 26, 2018

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

It was a sunny, cool late August morning as high school football practice kicked off around the state. The Detroit Tigers were in the midst of a four-game losing streak, their longest to date that World Series-winning season. With 32 games to go, their lead over the Baltimore Orioles was cut to five in the race for the 1968 American League pennant.

Hal Schram, Michigan’s revered prep sports writer, kicked off the start of the season with a trip north. He was on a mission designed to tie up loose ends.

Schram had been covering high school sports in the Great Lakes State since 1941 and began his days at the Detroit Free Press in January of 1945. He had named the 1967 Bay City Central team Michigan’s top Class A squad the previous November. After posting a 9-0-0 season, the school was scheduled to receive a trophy from the newspaper signifying the achievement. However, in mid-November, Detroit’s newspapers began a 267-day strike – the longest in history at the time – that interrupted a planned presentation.

So on Monday, August 25, 16 days after the end of the strike, Schram headed to Bay City. There, he visited with coach Elmer Engel and his staff, then handed off the impressive award before a group of 220 football hopefuls who reported for practice.

“It should give us added impetus in the weeks ahead,” said the veteran coach, accepting the trophy. This wasn’t a first for Engel and his squads. Entering his 19th year as head coach at Bay City, he had turned the Wolves into a state powerhouse. Back in the days before a postseason tournament, Central had edged unbeaten Battle Creek Central and seven other unbeaten and untied teams in the annual Free Press poll for the 1965 gridiron championship. In 1958, The Associated Press had named his squad the mythical state titlist. His teams had posted 129 wins against only 29 defeats and four ties since his arrival in 1950.

“It should give us added impetus in the weeks ahead,” said the veteran coach, accepting the trophy. This wasn’t a first for Engel and his squads. Entering his 19th year as head coach at Bay City, he had turned the Wolves into a state powerhouse. Back in the days before a postseason tournament, Central had edged unbeaten Battle Creek Central and seven other unbeaten and untied teams in the annual Free Press poll for the 1965 gridiron championship. In 1958, The Associated Press had named his squad the mythical state titlist. His teams had posted 129 wins against only 29 defeats and four ties since his arrival in 1950.

At age 25, Engel had enlisted in the Marines. As a 25-year-old second lieutenant he led his troops “in one of the most desperate, and bloody, battles of World War II – Iwo Jima.” Previously, he had earned three football letters at the University of Illinois and was the team’s MVP in 1942.

In baseball circles, 1968 has been called “The Year of the Pitcher.” On September 14, Detroit’s Denny McLain became the first hurler to win 30 games since Dizzy Dean in 1938. Bob Gibson, star of the St. Louis Cardinals rotation, turned in a 1.12 earned run average, the lowest in the Major Leagues since 1914.

The year 1968 also has been called “The Year that Shattered America.” With the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in April in Memphis, riots broke out in more than 100 cities across the United States. Protests continued to rage across the country over the war in Vietnam. Demonstrations, peaceful and violent, were raised around the world in support of civil rights.

The world was changing; by year’s end, Shirley Chisholm had become the first black woman elected to U.S. Congress. At Yale, moves were made to finally admit female undergraduates. In December, three astronauts aboard Apollo 8 became the first humans to orbit the moon.

High School football season began tragically in Michigan. Only a day before prep season openers, 17-year-old senior Jerry Knight died from a brain injury suffered in a scrimmage. Jerry and his twin brother, Pat, were scheduled to start in the backfield for Grand Rapids Catholic Central. It was reported that this was the first reported football death in the city of Grand Rapids since 1926. In total, 26 football players in middle school or high school across the nation would die that season, a peak that would spur slow changes within the sport.

The reigning Class A champs began the 1968 season at No. 1 in the state’s three prep football polls, published by Schram in the Free Press and the state’s wire services, The Associated Press (AP) and United Press International (UPI) following the second game of the season.

Only days before, the Tigers had clinched the pennant. Three weeks into the high school season, Bay City Central, with victories over a pair of Flint area schools and Saginaw Arthur Hill, remained firmly planted at the top. Battle Creek Central, winner in 32 of its last 33 games, was ranked No. 2, while Detroit Denby, the 1963 Free Press champion, was ranked third.

While the Tigers and St. Louis, the National League pennant winner, were preparing for their World Series opener, Schram was dealing with an overzealous fan as prep teams readied themselves for the fourth week of the season.

“This is the week we make your ratings look sick,” said a long-distance caller from Midland. “I’m telling you we’re going to run down your No. 1 team at Bay City Central. We’ve run three-straight and you’ve never even given us a courtesy call.”

“The man’s right about one thing,” said Schram in his weekly column highlighting the top contests from around the state. “The Midland-Bay City Central game Friday night certainly rates a top berth among Top Ten Games of the Week. … While Friday’s game with the defending state champions is of primary importance, the Midland team can’t be blamed for taking a quick peak on their TV sets at the World Series. One of their former All-State quarterbacks, Larry Jaster, just might be pitching for St. Louis against the Tigers.”

“The man’s right about one thing,” said Schram in his weekly column highlighting the top contests from around the state. “The Midland-Bay City Central game Friday night certainly rates a top berth among Top Ten Games of the Week. … While Friday’s game with the defending state champions is of primary importance, the Midland team can’t be blamed for taking a quick peak on their TV sets at the World Series. One of their former All-State quarterbacks, Larry Jaster, just might be pitching for St. Louis against the Tigers.”

No doubt to the joy of the caller, Midland ruined Bay City’s homecoming with a 12-7 win before a crowd of 7,000. With the loss, the Wolves fell to seventh in Schram’s rankings while Midland’s Chemics made their first appearance, entering the Free Press list at No. 4. With Bay City’s loss, Battle Creek Central, the 1966 Class A champ, moved to the top spot across the state’s three polls.

Just a year before, Battle Creek had been in the same position. Like Bay City, the Bearcats had followed their 1966 title by opening the next season ranked No. 1. Riding a 27-game win streak dating back to November of 1964, Battle Creek saw the run end in the eighth week of the 1967 season when 6-A Conference rival Kalamazoo Central nipped the Bearcats, 7-6, on a rainy, windy night at Kalamazoo College’s Angel Field.

“We’re not a holler team,” Battle Creek Central coach Jack Finn said to the Free Press sports editor, Joe Falls, prior to that Kalamazoo game. “We try to keep our kids at an even keel. No, we try to keep the emotion out of it.”

Following the contest, “Finn was pacing the room like a grizzly bear,” wrote Falls.

“‘That’s part of growing up’ he said.

“’Look at these kids – they never lost before. They don’t know how to take it.’”

“Finn consoled one player, then walked back across the room. ‘A test for the kids?’ he said, finally managing a weak smile. ‘This is a test for me. The last time we lost I woke up in the morning and vowed I’d never coach again.’”

Both Finn and Falls knew that defeat was an integral part of kids growing up.

But with Battle Creek’s loss, Bay City moved to the top spot. A week later, the Wolves picked up their ninth win, and with it, the 1967 mythical state crown.

Finn’s 1968 Bearcats had started the season slowly, downing Benton Harbor 14-0 in the season opener and then surviving an early-season scare on the road with Ann Arbor Huron, 6-0, before knocking off conference foe Lansing Eastern in the season’s third week, 27-6. Grinding out 455 yards on the ground, the Bearcats mauled East Lansing, 41-0, in Week 4.

Finn’s 1968 Bearcats had started the season slowly, downing Benton Harbor 14-0 in the season opener and then surviving an early-season scare on the road with Ann Arbor Huron, 6-0, before knocking off conference foe Lansing Eastern in the season’s third week, 27-6. Grinding out 455 yards on the ground, the Bearcats mauled East Lansing, 41-0, in Week 4.

“We were a very balanced team with lots of very good players, but no great ones,” recalled Terry Newton, a first team all-state choice at center in 1968. “We were kind of unheralded with a very tough defense.”

“This is perhaps the best balance squad (Coach) Finn has ever led into a season,” wrote Schram at the time, announcing the change at the top of his Class A poll. “Against East Lansing, Battle Creek used eight running backs almost of equal stature. John Simms, a junior who doesn’t even start, has rushed for 233 yards in 21 carries in his last two games. He’s one of southern Michigan’s foremost breakaway runners.”

On Thursday, October 10, the Detroit Tigers clinched Game 7, 4-1, to win the World Series. The following evening beneath the lights of Memorial Stadium, the Bearcats had their hands full in a game played in Lansing.

“For at least one night, Sexton was the equal of Michigan’s No. 1 prep football team, Battle Creek Central,” wrote Dave Matthews in the Lansing State Journal. “It didn’t work out quite that way on the scoreboard, Battle Creek rallying for a 14-13 decision … but the final tally could not erase a stirring upset attempt by the Big Reds.”

Late in the contest, Battle Creek took advantage of an injury to Lansing Sexton’s all-city tackle, Tom Bush. According to the Journal, the Bearcats pounded the left side on nine out of 10 plays, driving 65 yards, with Simms scoring from two yards out with 2:01 remaining in the contest to knot the score. Ernest English kicked the extra point to give Battle Creek its first lead of the game. Prior to Bush’s departure, the Bearcats had been held to a single first down in the second half.

Late in the contest, Battle Creek took advantage of an injury to Lansing Sexton’s all-city tackle, Tom Bush. According to the Journal, the Bearcats pounded the left side on nine out of 10 plays, driving 65 yards, with Simms scoring from two yards out with 2:01 remaining in the contest to knot the score. Ernest English kicked the extra point to give Battle Creek its first lead of the game. Prior to Bush’s departure, the Bearcats had been held to a single first down in the second half.

Midland, with a convincing 48-6 triumph over Saginaw Arthur Hill, was now entrenched at No. 2 and nipping at the heels of the Bearcats in the Associated Press and United Press polls. The AP rankings were based on a “10 points for first, nine for second, eight for third, and so on” voting system by state sportswriters and sportscasters. The UPI rankings were compiled based on the votes of a panel of 17 football coaches from across the state. Schram still ranked Midland at No. 4, trailing Battle Creek, but noted that the Chemics and their coach Bob Stoppert had an outside chance at their second state title in 11 years.

“That would be nice, but we’re not ready to debate such matters,” the 51-year old Stoppert said to Schram as teams headed to Week 6 of the season. “I’m too old to be impressed by the polls. I know the fans and the kids like them, but they’re a nuisance as far as a coach is concerned. If you fellows would wait until the end of the season to rate your teams, I wouldn’t have any objections. But I know you’re not going to listen to that.”

No changes occurred that week, as the Bearcats trounced 6-A conference foe, Jackson, 56-0 and Midland rolled over Saginaw Valley Conference opponent Alpena, 38-0. A loss by Grand Rapids Union boosted the Chemics to third in Schram’s rankings.

Battle Creek squared off against Ann Arbor Pioneer, ranked No.5 in the polls by both AP and UPI in Week 7.

With Battle Creek trailing the Pioneers 7-0 at the half, Jim Roebuck nailed a 34-yard field goal in the third quarter to make it 7-3. A huge goal-line stand late in the fourth quarter by Pioneer appeared to seal an upset, but three successive stops by the Bearcats’ defense prevented Ann Arbor from running out the clock. Following the punt, Battle Creek took over on the Pioneers’ 42 with 2:30 to play. A touchdown by Simms with 1:18 left gave the Bearcats a 9-7 victory.

United Press voters were impressed with the comeback and kept Battle Creek at No. 1, rewarding the Bearcats with a widening point gap between first and second place in their poll. Midland had downed league opponent Flint Northern, 28-12, and, in the eyes of AP voters, the Bearcats and Chemics were now tied for No. 1 as the season headed for the finish line.

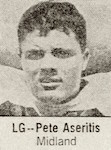

“In those days, the Saginaw Valley was considered perhaps the toughest conference in the state,” said Peter Aseritis, who captained the Chemics in 1968. “Back then, eight of our nine games were against conference opponents.”

“In those days, the Saginaw Valley was considered perhaps the toughest conference in the state,” said Peter Aseritis, who captained the Chemics in 1968. “Back then, eight of our nine games were against conference opponents.”

The Bearcats avenged the previous year’s loss to Kalamazoo Central, 31-7, while Midland downed Bay City Handy 27-7 in Week 8. While the Free Press and UPI kept Battle Creek on top, AP voters pushed the Chemics to No. 1 in their list by a single poll point.

Prior to season’s end, Schram set the stage for football fans across the state.

“While close to 7,000 fans are expected at Post Field for this (week’s) intra-city showdown (between Battle Creek Central and Battle Creek Lakeview), Midland goes after its first perfect season since 1957 at Saginaw where another crowd of 6,000-plus is anticipated. At stake will be the Saginaw Valley League title. Midland holds the No. 3 rating in the state and Saginaw is ranked No. 4.”

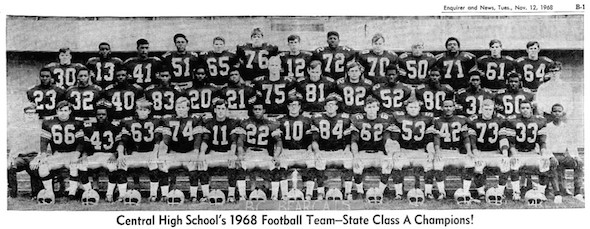

“This is the greatest gang of seniors we ever have had at Central … they never gave up … yes, I definitely feel that we are No. 1 in the state,” said Coach Finn to Bill Frank of the Battle Creek Enquirer “as he came dripping out of the shower, clothes and all” following Central’s 19-7 win over Lakeview. It was the third perfect season for the Bearcats in four years, and only the fourth perfect campaign in school history.

Midland defeated Saginaw 20-13.

“There was some violence after the game,” noted Aseritis. “Some fans were upset. Rocks were thrown at our bus; some windows were broken.”

Both the Detroit Free Press and the United Press International season-ending polls named Battle Creek at No. 1. The Associated Press saw it differently, awarding Class A’s mythical crown to Midland while placing the Bearcats tied for third with Ferndale. Unbeaten in eight games, Detroit Denby finished second in the AP rankings, compiling 131 poll points to Midland’s 135. Midland received seven first place votes to three for Denby. Battle Creek ended with 129 points and five first-place votes.

Without the structure of a playoff system, there was no chance that the two top-ranked teams would meet on the gridiron.

“There is a certain level of charm to the time of mythical state titles. Winning a conference championship was much more important back before the arrival of the playoffs and today’s focus on six wins,” said Newton, who went on become athletic director at Battle Creek St. Philip, a member of the Battle Creek Parks and Recreation department and the radio voice of prep sports in Battle Creek as host of ‘Coach’s Corner’ on WBCK for more than 25 years.

“There is a certain level of charm to the time of mythical state titles. Winning a conference championship was much more important back before the arrival of the playoffs and today’s focus on six wins,” said Newton, who went on become athletic director at Battle Creek St. Philip, a member of the Battle Creek Parks and Recreation department and the radio voice of prep sports in Battle Creek as host of ‘Coach’s Corner’ on WBCK for more than 25 years.

“It was a great time at Battle Creek Central. We had a lot of winning tradition,” continued Newton. “For five or six years, Bay City and Battle Creek dominated (Class A) football. I think that some voters fell in love with Midland that year, and that split the vote. But we were the champs according to Hal Schram. That was the big one. He really was the state’s top prep sportswriter.”

“On the weekend of October 12th and 13th back in Midland, the team will reunite to celebrate the 50th anniversary of their title. On Friday, the school plans to honor us during the game,” said Aseritis, who also earned first team all-state honors in 1968. “I won’t make it back for that. My son is a senior at Elk Rapids. He has a game and I plan to be there, but I expect to be in Midland on Saturday for our reunion. As players we got a piece of it.

“Back then, it was ground and pound; a real physical game. Today, the game is wide open and space. Of course, back then we only had to play nine games. You got to hand it to those who get to the state title game today. Now, kids have to play 14.

“We had it easy,” he added, laughing.

Fifty years down the road for both men, the camaraderie and chance to learn to work with others toward a common goal still stand out from those days.

“Yes, I recall certain days from my career,” added Aseritis, a former Marine Corps captain who traveled the world as a financial analyst and consultant. “My times playing high school football, college football and my years in the military are the days that mean the most. Those are lifetime memories.”

“Within the football program, the issues of the times never really came up,” said Newton reflecting on his days at Battle Creek Central. “The coaches never talked about it. They were focused on blocking and tackling. The players were focused on school and football. Our team came together from four different junior high schools at Central; it was a mixed community, maybe 50 percent black and 50 white.

“We had to come from behind a few times that season. That’s where you learn to work with other people; how to handle adversity and success, and deal with challenges. We had great camaraderie, and that allowed us to have the success we had.”

After stints at Dansville, Hudson and Coldwater high schools, Finn held the football reigns at Battle Creek Central for 11 years. He stepped aside following the 1968 season to take on the dual role of athletic director and head football coach at Northwood Institute in Midland. At Northwood, he helped found the Great Lakes Intercollegiate Athletic Conference. He retired as the school’s football coach following the 1986 season and as AD in 1989. He died in 2013.

Elmer Engel and his Bay City squad again would grab the Class A title in 1969 and in 1972. He retired after the 1972 season with a 165-34-8 record and five mythical state titles. In 1973, the school chose to rechristen its football stadium in his honor in recognition of his incredible success. The classic concrete structure was built in 1925. Engel died in 2006 at age 86.

Stoppert stepped aside following the 1974 season. A Flint Northern graduate, he had coached briefly at Flint Bendle and Rockford before being named head football coach at Midland in 1953. The Chemics posted 128 victories, 58 losses, six ties and two mythical gridiron championships during that span. He died in 2003.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS:

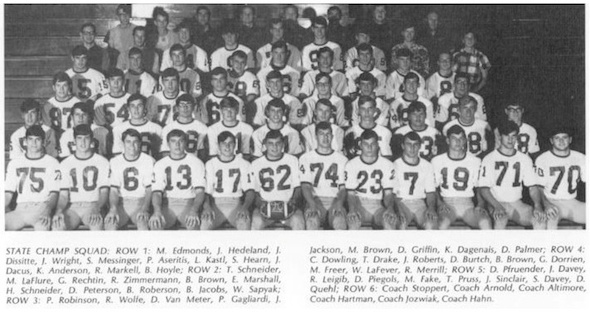

(Top) Battle Creek Central’s Terry Newton (53) and Jim Roebuck tackle Battle Creek Lakeview’s Dave Roberts during their 1968 game. (2) Hal Schram presents Bay City Central with the 1967 Detroit Free Press Class A championship trophy. (3) Bay City Central coach Elmer Engel and a player during the 1967 season. (4) Battle Creek Central coach Jack Finn. (5) Battle Creek Central’s Terry Newton. (6) Midland coach Bob Stoppert. (7) Midland’s Pete Aseritis. (8) Battle Creek Central’s 1968 championship team. (9) Midland’s 1968 championship team. (Photos gathered by Ron Pesch.)

1st & Goal: 2025 Playoffs Week 3 Review

By

Geoff Kimmerly

MHSAA.com senior editor

November 18, 2025

The third weekend of these MHSAA Football Playoffs saw plenty of headlining moments.

Three first-time Regional champions and a team advancing to a Final for the first time.

Three statewide stunners – including two in Division 4 alone.

One team accomplishing something from all of the above on what had to be the most unforgettable night in that program’s history.

Add in the usual high-level matchups to be found this time of year, and it was a wild 48 hours across both peninsulas. See below for notes on all 36 games.

8-Player Division 1

HEADLINER Blanchard Montabella 32, Norway 28 Montabella (11-1) came back from a 28-8 halftime deficit to earn its first trip to an MHSAA championship game in this sport. The defeat was the only one this season for Norway (11-1), which was playing in its first Semifinal since 2006. Click for more from the Greenville Daily News.

HEADLINER Martin 20, Kingston 8 The Clippers (12-0) also trailed at halftime before scoring 20 unanswered points to earn their third Finals trip over the last four seasons. Kingston ended 10-2, with its highest win total since 1996. Click for more from the Kalamazoo Gazette.

8-Player Division 2

HEADLINER Felch North Dickinson 44, Onekama 28 The Nordics (12-0) will play for a Finals championship for the first time since 1998 after finding their stride against an Onekama defense that otherwise gave up only 11.5 points per game this season. The Portagers finished 11-1, setting a school record for victories. Click for more from the Iron Mountain Daily News.

HEADLINER Portland St. Patrick 36, Deckerville 15 St. Patrick denied Deckerville (10-2) a return trip to Superior Dome as the Eagles sought to add to their Division 1 title won a year ago. Instead, the Shamrocks (12-0) will play in their first Final since 2020, and after holding Deckerville to its fewest points since also scoring 15 in Week 1. Click for more from WLNS.

11-Player Division 1

HEADLINER East Kentwood 52, Hudsonville 28 The Falcons (10-2) avenged a 43-42 Week 7 loss to eventual Ottawa-Kent Conference Red champion Hudsonville, in doing so handing the 2024 Division 1 runner-up Eagles (11-1) their only defeat this fall. The Regional title was East Kentwood’s first since 2014 and came in part thanks to three rushing touchdowns and two passing scores from quarterback Kayd Coffman. Click for more from the Grand Rapids Press.

Regional Roundup Detroit Cass Tech 42, Saline 28 The reigning Division 1 champion Technicians (12-0) ran their winning streak to 23 as C.J. Sadler scored four touchdowns to help end Saline’s run at 10-2. Detroit Catholic Central 42, Clarkston 13 The Shamrocks (12-0) clinched a second-straight Regional title, opening a 28-7 lead by halftime and holding Clarkston (10-2) to its fewest points this fall. Rochester Adams 29, Romeo 13 The Highlanders (10-2) also won a second-straight Regional title, adding to a 39-7 win over Romeo (8-4) in their season opener.

11-Player Division 2

HEADLINER Dexter 56, Gibraltar Carlson 42 The Dreadnaughts (11-1) won their second Regional title in four years and this time by scoring their second-most points in a game this fall. Carlson (11-1) – which set a school record for wins this season – had opened up a two-score lead during the third quarter before Dexter stormed back. Quarterback Cooper Arnedt threw for 590 yards and eight touchdowns. Click for more from the Ann Arbor News.

Regional Roundup Portage Central 24, Traverse City Central 20 A lot of Portage Central headlines have gone to the defense this fall, but the offense earned this one as the Mustangs (12-0) took the lead in the fourth quarter and held onto the ball late to deny the Trojans (7-5) one more comeback attempt. Orchard Lake St. Mary’s 42, Midland Dow 7 The reigning Division 2 champion Eaglets (9-2) hit the road and scored their most points since Week 6, while also holding Dow (10-2) to its season low. Birmingham Groves 37, St. Clair Shores Lakeview 14 After starting this season 2-3, Groves (9-3) hasn’t lost since September and added a second-straight Regional title while ending a record-setting run for Lakeview (9-3) – which made an awesome jump from 3-6 a year ago,

11-Player Division 3

HEADLINER Warren De La Salle Collegiate 38, Detroit Martin Luther King 20 The Pilots opened up a 24-6 lead by halftime and kept King (7-5) – the reigning Division 3 runner-up – from reaching the Semifinals for the first time since 2020. De La Salle (6-6) has won five of its last seven games, and this was its fifth Regional title in six seasons after last year’s run ended in this round. Click for more from the Macomb Daily.

Regional Roundup Lowell 36, Zeeland West 34 The Red Arrows (10-2) moved past the reigning Division 3 champion Dux (8-4) late, earning their first Regional title since 2016. DeWitt 70, Fenton 26 The Panthers (12-0) reached 70 points for the second time this playoffs to advance to the Semifinals for the seventh time over the last eight seasons, ending Fenton’s longest run since 2016 at 8-4. Mount Pleasant 28, East Grand Rapids 14 The Oilers (12-0) earned their first trip to the Semifinals since 2011 and ended East Grand Rapids’ winning streak at seven games and season at 9-3.

11-Player Division 4

HEADLINER Dearborn Divine Child 10, Harper Woods 6 Divine Child is 11-1, so deciding a degree of upset here is difficult – but Harper Woods (11-1) had defeated Division 1 Saline and Clarkston among others this season and was ranked No. 1 in the final coaches poll, so this made a pretty big statewide wave. The Pioneers were seeking a third-straight Regional title, and Divine Child claimed its first since 2016. Click for more from the Detroit Free Press.

Regional Roundup Vicksburg 42, Portland 41 The Bulldogs (8-4) pulled off another of the stunners of these playoffs, clinching their first Regional title in this sport with a walk-off touchdown catch to hand Portland (11-1) its only defeat of the season. Hudsonville Unity Christian 52, Big Rapids 14 Unity Christian (11-1) won its first Regional title since 2021 with its sixth 50-point game this season, and also held Big Rapids (10-2) to the Cardinals’ season low. Goodrich 41, Williamston 33 The reigning Division 4 champion Martians (12-0) won this matchup of undefeated contenders, ending the Hornets’ longest run since 2020 at 11-1.

11-Player Division 5

HEADLINER Pontiac Notre Dame Prep 42, Frankenmuth 28 This rematch of last season’s Division 5 Final was much closer, but Notre Dame Prep prevailed again as quarterback Sam Stowe through three touchdowns passes and the Fighting Irish (10-2) also returned a blocked punt for a score. Frankenmuth finished 10-2, its only other loss to still-undefeated Goodrich during Week 1. Click for more from the Oakland Press.

Regional Roundup Ogemaw Heights 34, Saginaw Swan Valley 14 Ogemaw Heights (11-1) clinched its first Regional title since 2009, holding Swan Valley (10-2) to its fewest points since also scoring 14 in its only other loss this fall in Week 2. Grand Rapids West Catholic 27, Kalamazoo United 0 The Falcons (11-1) posted their first shutout since Week 2, and scored the most points the Titans (9-3) gave up in a game this fall. Monroe Jefferson 71, Michigan Center 45 This one will make the highest-scoring games list for this season, as Jefferson (11-1) scored its most since 2010 and Michigan Center (10-2) went over 40 for the eighth time this season.

11-Player Division 6

HEADLINER Kent City 50, Montrose 20 Kent City (12-0) added a first Regional title to its first District championship won the weekend before, reaching 50 points for the third time this season and after Montrose had given up only 62 points combined over its first 11 games. The Rams completed their winningest season since 2013 at 11-1. Click for more from the Muskegon Chronicle.

Regional Roundup Almont 44, Detroit Edison 8 After edging Edison 53-46 in Week 9, Almont (12-0) pulled away this time to claim a second Regional title in three seasons. The Pioneers set a program record for wins in finishing 9-3. Jackson Lumen Christi 21, Ida 7 The reigning champion Titans (9-3) turned away their strongest challenge since the start of October, and after defeating Ida (9-3) by 21 in a District Final a year ago. Kingsley 18, Reed City 14 The Coyotes (9-3) cut the margin after Kingsley (10-2) won their season-opening meeting 24-6, but the Stags prevailed scoring the go-ahead points on a fourth-down pass.

11-Player Division 7

HEADLINER Clinton 20, Millington 18 This was another classic decided during the final minute, as Clinton (10-2) went ahead on a scoring pass to end Millington’s repeat Division 7 championship hope and season at 9-3. The Regional title was Clinton’s first since 2022. Click for more from the Adrian Daily Telegram.

Regional Roundup Menominee 43, Shelby 0 The Maroons (12-0) have been tough on defense all season, allowing just 10 points per game on average, but they threw their first shutout in ending Shelby’s longest run since 2013 at 7-5. Pewamo-Westphalia 42, Ithaca 21 The Pirates clinched their first Regional title since 2021 and improved to 11-0, running their playoff record against Ithaca (8-4) to 3-0 over the last five seasons. Schoolcraft 22, Hanover-Horton 14 Schoolcraft (10-2) scored the only points of the fourth quarter to claim a second-straight Regional title. Hanover-Horton finished 9-3, setting a program record for wins.

11-Player Division 8

HEADLINER Harbor Beach 26, Beal City 15 The Pirates (12-0) won their first Regional title since 2018 and ended the season for reigning Division 8 champion Beal City (11-1). Harbor Beach continued its impressive defensive run, with the Aggies’ 15 points the most the Pirates have given up – and with Beal City averaging nearly 46 per game entering the weekend. Click for more from the Huron Daily Tribune.

Regional Roundup Hudson 68, Springport 22 The Tigers (12-0) continued their perfect run, scoring their second-most points this fall in handing Springport (11-1) the only loss of its winningest season. Bark River-Harris 22, Maple City Glen Lake 21 The Broncos (10-1) secured their first Regional title since 2003 with a kickoff return touchdown and 2-point conversion on the final plays of the game. Glen Lake (9-2) had scored just seconds earlier to break a 14-14 tie. Allen Park Cabrini 34, Madison Heights Madison 32 The Monarchs’ first Regional title came with a go-ahead touchdown during the fourth quarter, sending Cabrini to 11-1 and ending Madison’s season at 10-2 – an incredible turnaround after the Eagles had won a combined six games over the previous five seasons.

MHSAA.com's weekly “1st & Goal” previews and reviews are powered by MI Student Aid, a division within the Department of Lifelong Education, Advancement, and Potential (MiLEAP). MI Student Aid encourages students to pursue postsecondary education by providing access to student financial resources and information. MI Student Aid administers the state’s scholarship and grant programs that help make college Accessible, Affordable and Attainable for you. Click to connect with MI Student Aid and find more information on Facebook and Twitter @mistudentaid.

PHOTOS (Top) Portland St. Patrick running back Brady Leonard (9) accelerates through a hole during the first quarter of his team’s 8-Player Semifinal win Saturday over Deckerville. (Middle) Detroit Catholic Central quarterback Duke Banta targets a receiver during his team’s Division 1 Regional Final win Friday over Clarkston. (St. Patrick/Deckerville photo by Kolleth Photo. DCC/Clarkston photo by Terry Lyons.)