Howell Names Field for Longtime Leader

August 30, 2018

By Tim Robinson

Special for Second Half

If you got the impression that John Dukes has been around Howell football forever, you wouldn’t be far off.

His association with the program began before high school.

His association with the program began before high school.

“When I was a kid, I used to live near Page Field (Howell’s former athletic complex), and I would go out and watch football practice,” Dukes said. “I was at practice all the time, and the coach said, ‘If you’re going to be here all the time, you may as well get some water for the boys while they’re practicing.’”

That was in 1963, when the Highlanders went 9-0.

A little more than 55 years later, Dukes will be honored tonight when the field at Howell’s Memorial Stadium will be named John Dukes Field.

Howell football coach Aaron Metz began the drive to name the field after Dukes when it was determined the old turf, installed in 2004, needed to be replaced.

“We have a commitment award named for John,” he said. “If you play football for four years, you get the John Dukes Commitment Award. We put a committee together with people who have been around Howell for a long time, and when you ask anybody, they say there’s not a person more deserving than John Dukes.

“So I ran it up the ladder to the athletic director and superintendent, and, to be honest, it was a pretty easy process because no one could find anything bad about John,” Metz added. “We’re excited to have the opportunity to do it.”

Dukes was a three-year varsity player at Howell and then played at Alma College, where his teams won three league championships.

With the exception of six years at Hartland coaching under his son, Marcus, John Dukes has been affiliated with Howell football for 46 years, including 25 as the head coach.

After graduating from Alma in 1972, Dukes got a teaching job at Howell and was an assistant freshman coach for a season and a varsity assistant for two before taking over as head coach at age 25.

“My philosophy at the time was I wanted to help the kids enjoy playing football and help them to be successful at it,” he recalled. “The previous three years our record wasn’t very good. That was one of my objectives, was to make it fun.”

He then talked about his first season with a little self-deprecation, a common thread in most conversations with Dukes.

“I remember my first game,” he said. “Because I played defense in college (Dukes was a linebacker), I thought we were going to be a really good defensive team. We played Fenton in my first game, and we lost 32-19, so my defensive prowess wasn’t good at the time.”

The Highlanders lost six of their first seven games that season, but won the last two and went 8-1 three seasons later.

In all, Howell had winning records in 15 of his 25 seasons, but one group of players stood out for an entirely different reason.

“We had a period of time (1989 and 1990) where we weren’t very good, and we lost 17 games in a row,” he said. “But those kids were wonderful kids to coach. They came to practice with energy all the time, and from a coaching standpoint, it was wonderful to coach them during the week. Now, Fridays were a different story, because we didn’t play very well on Fridays, ever.

“But the real thing that stands out with that group was the very last game of their senior year we beat (Waterford Kettering), and you’d have thought we’d won the Super Bowl,” Dukes continued. “Those kids who were seniors, that was their first football victory in high school. It was an amazing time. We had several teams with good players, and I really enjoyed coaching them, too, and I don’t want to leave them out. But that really stood out in my mind, in that they came out to work every day.

“But the real thing that stands out with that group was the very last game of their senior year we beat (Waterford Kettering), and you’d have thought we’d won the Super Bowl,” Dukes continued. “Those kids who were seniors, that was their first football victory in high school. It was an amazing time. We had several teams with good players, and I really enjoyed coaching them, too, and I don’t want to leave them out. But that really stood out in my mind, in that they came out to work every day.

“Over a period of time of losing that many games, sometimes, it’s not fun and it’s not fun for them or the coaches. But we had a very enjoyable time over that two-year period, regardless of the fact we didn’t win any games.”

His perspective is consistent with the principles by which he ran his program.

“These weren’t original to me,” he says, “but the three things I always told our kids was your faith should be your number one priority, your family should be your number two priority. Football, when school hadn’t started, should be number three. And when school started, school became three and football became number four. We tried to base everything we did on these priorities in our lives. Sometimes those things cross over and mix and match. When they do, then you have to step back and say what is really important here?”

Dukes resigned after the 1999 season.

“There were a lot of things and I don’t know if anything in particular,” he said of his decision. “I had been doing it for 25 years, and we had a string of years where we were 6-3. So we were OK, but I felt it was time to be done with it.”

His self-imposed exile lasted one season. He had a couple of stints as an assistant coach when he finally decided to retire for good in 2006.

“No sooner had I done that, my son (Marcus) called me up and said he just got the Hartland job,” Dukes recalled. “He said, ‘Dad, you have to come here and help.’ So I went there for six years. Then he resigned, and I thought I was going to be done again.”

After another stint as a Howell assistant, John Dukes took the last two years off before agreeing to rejoin the program as a junior varsity assistant this season, as the offensive coordinator.

As it turns out, one grandson, Jackson Dukes, plays on the Howell JV, and John Dukes also is helping coach another grandson, Colin Lassey, on his junior football team.

“When Jackson gets home, I ask him, ‘Did you get yelled at by Grandpa today?” Josh Dukes says. “And when he says yes, I say, ‘Good. You should be getting yelled at.’ So nothing has changed in the 30 years since high school.”

Josh Dukes, the oldest of John Dukes’ three children, joined Marcus in playing football for their father.

“There was never an expectation that we had to be this or that,” Josh Dukes said of himself, his brother and sister, Carrie. “Now maybe he was a little harder on me, but that’s something we were thankful for. I’d rather him be harder on me than any kid on the field, because then the other kids left me alone. They knew it was the same for everyone across the board. He wasn’t going to take it easy on me, my brother or my sister.”

John Dukes coached his daughter, Carrie, when she played middle school basketball.

“The first time he coached me, he came home to my mom and said, ‘I don’t know how people do this,’” she recalled. “‘They’re all crying, half of them don’t think I like them. I don’t know how to do this with girls. It’s a totally different ballgame.’ But he was a great coach. I know some people don’t like their parents coaching them, but I loved having him coach.”

Like her brothers, Carrie Lassey stayed involved with sports. She is now the athletic director at St. Joseph Catholic School in Howell.

“He coached my freshman team a couple of years ago,” she said. “It was third and fourth-grade girls. It’s amazing. He can coach pretty much anybody.”

Indeed, Dukes also coached baseball and wrestling at the varsity level at Howell, and, for a couple of weeks, filled in as a competitive cheer coach when the Highlanders had a temporary vacancy.

“I was more a supervisor,” he said, but serving that role illustrated his commitment to the athletic program as a whole. He was needed, and he stepped in.

Having stopped and started his career so many times, Dukes, now 68, laughs when asked about what he will do when he retires in the distant future.

Having stopped and started his career so many times, Dukes, now 68, laughs when asked about what he will do when he retires in the distant future.

“I’m sure he’ll be coaching when he’s in his 90s. Maybe triple digits,” jokes Bill Murray, the former Brighton coach who matched up with Dukes’ teams during the second half of Dukes’ Howell tenure. “The guy loves the game, he’s out there and he has a lot to offer. His teams were always well-prepared, they played great defense, were fundamentally sound and when you went nose-to-nose, they were consistent as to what they were going to do. It was a matter of whether you could stop them or not.”

Dukes still keeps up with the Howell varsity, still offers advice when asked, and still enjoys the competition.

“For me, as a head coach, it’s great having a coach (on staff) who has been there and done it to talk to and mentor, even me,” Metz said. “What makes a successful coach, I don’t think, changes, whether it’s been 50 or 100 years ago to the current day. He steered the ship to have an outstanding record (130-95) and also have a huge impact on kids in our community.”

“When people talk to me about my dad, they say he was a dad to them, or like a second dad,” Josh Dukes added. “Or, ‘I wanted to be a teacher because of him.’ These are the things that for us,” referring to his siblings, “is the most impressive part. The kids of players he’s coached, or the grandkids.”

Dukes has the unusual distinction of having coached more congressmen (Mike Rogers and Mark Schauer, who started on the offensive line for Dukes in the late 1970s) than pro football players (Jon Mack, who played for the Michigan Panthers of the USFL in 1984).

John Dukes will give a short speech before tonight’s ceremony, which will take place before Howell’s home opener against Plymouth.

“They’ve given me five minutes, but it will probably be shorter because they want to get the game started on time,” he joked.

“It’s an incredible honor,” Josh Dukes said. “Everyone in our family feels the same way. I don’t think he ever went into this with any intentions of being singled out. It’s a great lesson for our community and our athletes, to see what hard work and effort and care for your community can do, you know?”

During the ceremony, the letters “John Dukes Field,” which were sewn into the artificial turf in Howell’s Vegas Gold, will be unveiled.

“Aaron showed it to me last week when they were putting it in,” John Dukes said, then joked, “I thought (the lettering) was going to be a little trademark sign (sized), and my goodness, it’s bigger than the numbers. It’s a little bit ostentatious for me, I think; wow, that’s quite a tribute. I’m very humbled by it and honored by it and very appreciative of what people have done to make this happen.”

A few days later, Dukes posed for a picture next to his name on the field and chatted with a reporter as they left the stadium.

Then, he turned a corner to the JV football office and kept walking.

Before he became a living legend, John Dukes was a football coach, and there’s a game coming up and his team to prepare.

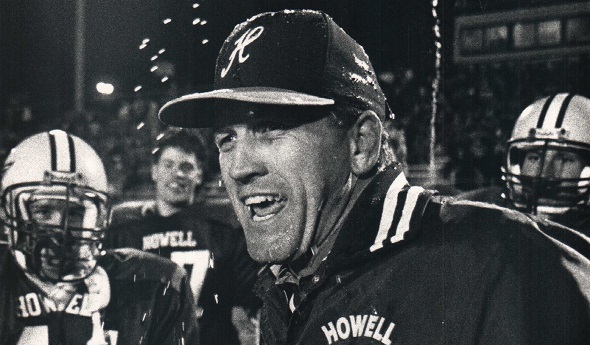

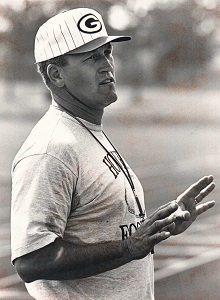

PHOTOS: (Top) Howell coach John Dukes celebrates his team’s 38-0 playoff victory over Wayne Memorial in 1992. (Middle) Dukes, during the 1991 season. (Below) Dukes stands next to the lettering that will be unveiled Thursday when the school’s field is named in his honor. (Photos taken or collected by Tim Robinson.)

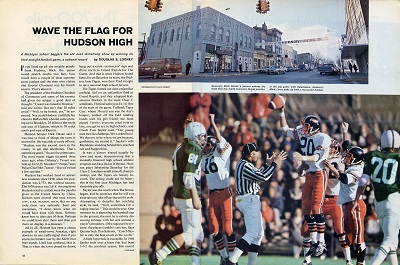

Flag Waves for Record-Setting Hudson

November 24, 2015

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

The story of little Hudson High School had captured the minds of many back in the fall of 1975, but perhaps none more so then the one belonging to filmmaker Steve Gebhardt.

The small town, located south of Jackson, boasted a population of about 2,600 at the time. Student enrollment placed its high school firmly as Class C in a four-tiered system used by the Michigan High School Athletic Association to determine placement in MHSAA postseason tournament play.

On a cold day in Mount Pleasant at Central Michigan University, Gebhardt and crew, armed with cameras, captured the action. It was the first Class C title game in the state’s long history of prep football. The game matching Hudson’s Straight T and Ishpeming’s Slot I offenses also would serve as the conclusion to something amazing.

After losing their season opener in 1968 to Blissfield, Coach Tom Saylor’s Tigers began a march unseen in state high school history. Hudson finished out that football season with eight straight victories, but could not be found among the four squads with a single defeat ranked in the Associated Press top 10 poll for Class C. That changed a year later, when Hudson posted nine straight wins. The 1969 AP poll found the Tigers in second place behind only Frankenmuth’s undefeated squad at season end.

Nine dominating wins in 1970 brought the Tigers’ win streak to 26 straight. That Hudson squad, ranked among the best in school history, allowed a mere 24 points while scoring 372. Yet, again, the team landed in second place at the end of the year according to AP’s statewide panel, comprised of five members each from newspapers and radio/TV stations. According to the AP poll, Michigan’s Class C crown was instead awarded to a stellar Galesburg-Augusta team.

Nine dominating wins in 1970 brought the Tigers’ win streak to 26 straight. That Hudson squad, ranked among the best in school history, allowed a mere 24 points while scoring 372. Yet, again, the team landed in second place at the end of the year according to AP’s statewide panel, comprised of five members each from newspapers and radio/TV stations. According to the AP poll, Michigan’s Class C crown was instead awarded to a stellar Galesburg-Augusta team.

The 1971 season saw Hudson post a third consecutive 9-0 mark, and their 35th victory in a row, but again they finished the season as bridesmaids in the rankings behind North Muskegon. Tight wins in a pair of contests – an 8-0 victory over Harper Woods Lutheran East and a 6-0 defeat of Morenci in the traditional season finale – likely gave the nod to the Norseman, who had played only eight games that season.

With no control over the press polls, the Tigers coaching staff set its sights on another target – Michigan’s consecutive win streak of 44 gridiron games.

Hudson won the 1972 season opener against Blissfield, 16-3, and then rolled through its next six contests with relative ease. Game eight was against Homer, a team ranked among the top 10 in Class C all year. Suddenly, the streak was on the media’s radar.

“Little Hudson High Eyes 43rd in a Row” was the headline in the Detroit Free Press. “Winning streaks are made to be broken,” wrote the dean of state sports writers, Hal Schram. “Where will it end for little Hudson High?”

Saylor’s team trounced Homer 42-0 to ensure that the streak didn’t stop with the article.

Fittingly, the traditional season-ending battle with Morenci offered the chance to tie the state record for consecutive wins. As chance would have it, the Bulldogs held the long-standing mark in Michigan. Between 1948 and 1953, Morenci had posted 44 straight victories. The previous mark had been a 34-game winning streak by Detroit Catholic Central between 1936 and 1939.

Memories of the tight contest from 1971 were quickly forgotten as Hudson won easily, 42-0. With the victory, the Tigers were finally named Class C champs by the AP (but were still ranked second in Class C by United Press International), and Coach Tom Saylor was named AP Prep Coach of the Year.

A graduate of Deerfield High School in 1960, Saylor enrolled at Eastern Michigan University. At age 22 he accepted a teaching job at Hudson. After a year coaching the junior high team, and another as a junior varsity assistant, Saylor, was named varsity football coach in 1966 when Tiger coach Jack Zimmerman became principal at the Miller Building – the town’s elementary school.

The team became the record holder with a season opening 30-0 victory over Blissfield in 1973. However the streak was nearly ended by Manchester, a 6-0 win, in the season’s sixth game. Fullback Dan Bellfy scored the lone touchdown on a 4-yard run with 4:50 left in the first half.

“That was all the stubborn Tiger defense needed to work with,” noted the report in the Saturday, Oct. 20 edition of the Hillsdale Daily News. “Hudson coach Tom Saylor said, ‘Our defensive ends Don Hoover and Rick Beagle, did an outstanding job of pressuring (All-State quarterback Rick) Kennedy.’ (Dan) Mullaly came up with a big play as he intercepted a Kennedy pass at midfield with less than a minute left on the clock.”

Breathing a sigh of relief, the Tigers again ended the year undefeated, extending the streak to 53 straight wins. Hudson High was named mythical Class C state champ by the AP, but again UPI downplayed the success. Undefeated St. Ignace from the Upper Peninsula was named UPI champ, with second place awarded to once beaten Kalamazoo Hackett. The panel of eight different high school coaches that voted each week in the UPI poll felt “that if there was a playoff annually and it had to meet Hackett and St. Ignace,” Hudson would fall despite its lengthy winning streak. So instead, the Tigers finished third in the UPI Class C prep rankings.

Breathing a sigh of relief, the Tigers again ended the year undefeated, extending the streak to 53 straight wins. Hudson High was named mythical Class C state champ by the AP, but again UPI downplayed the success. Undefeated St. Ignace from the Upper Peninsula was named UPI champ, with second place awarded to once beaten Kalamazoo Hackett. The panel of eight different high school coaches that voted each week in the UPI poll felt “that if there was a playoff annually and it had to meet Hackett and St. Ignace,” Hudson would fall despite its lengthy winning streak. So instead, the Tigers finished third in the UPI Class C prep rankings.

The 1974 team extended the streak to 62. Of course, with a huge target on its back, pressure mounted throughout the year.

“The much-publicized battle between the top-ranked Tigers and the fourth-ranked (Addison) Panthers was everything the 6,000 rain-drenched fans could hope for,” stated the Hillsdale Daily News. Trailing 13-0 early, and 21-20 with 10:08 left in the contest, Hudson rallied back with a touchdown by Greg Guitierrez with 4:48 left in the fourth quarter for a 26-21 victory at Hudson’s Thompson Field in week three. Schram later called the contest “Prep Game of the Year.”

Two weeks later, Mark Luma, a junior running back for the Tigers, scored on the last play of the game to give Hudson a 14-8 road win over Grass Lake to keep the streak alive.

Hudson led 16-14 at halftime of the season finale with Hillsdale, but both teams were unable to score in the final two quarters, and Hudson capped a sixth straight undefeated season with its third consecutive Class C title according to the Associated Press.

“I was born and educated in Cincinnati,” said Steve Gebhardt, discussing his interest in the high school team from southeastern Michigan. “I stumbled on an article in a Detroit newspaper talking about the Hudson streak and its potential to gain this record next year. It seemed prophetic and I bit.”

The record that caught Gebhardt’s eye was owned by Jefferson City, Missouri. Between 1958 and 1966, the Jays compiled 71 straight wins on the gridiron.

A 1955 graduate of Cincinnati’s Walnut Hills High School, Gebhardt “worked at an architectural engineering firm for three years before enrolling in the University of Cincinnati to study architecture, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1964 and a master’s degree in community planning in 1968,” recalled the New York Times. “While at school he became infatuated with film. He founded the film society, (and) began making his own experimental 16-millimeter films.”

In 1970, he was invited to New York to work for a friend, Jonas Mekas, an avant-garde cinema pioneer. By 1972, Gebhardt was working as resident filmmaker for Joko Films, owned by former Beatle John Lennon and wife Yoko Ono. It was followed by work filming the Rolling Stones in Texas during their Exile on Main St tour.

Shortly after the 1974 season, the Michigan High School Athletic Association announced plans to host a state championship series for football in Michigan in the fall of 1975. The 1974 season had been spent studying the plan. Deemed a success, the coming season would see four teams selected from each of the four classifications selected to compete in a two-round playoff. Teams winning round one would pair off in a championship round, with the winner of that game proclaimed a true state champion, based on competition.

With Hudson’s streak now at 62, another undefeated season would mean they would tie the national record. If the Tigers qualified for the planned playoffs, the team would have the chance to top the mark in the opening round.

Gebhardt made contact with Saylor and school officials about the possibility of capturing the chase for the record on film for a possible documentary. Approved, with a film crew assembled, they joined the team for much of the 1975 season, shooting game film both in town and on the road. They caught a team focused on disappointing no one, including Saylor, the coaching staff, family, friends and classmates. After a period of adjustment, the presence of the crew provided more inspiration not to lose.

Prior to the start of the season, Saylor spoke of his optimism with the press.

''This is the group of kids we've been waiting for since they were in junior high. They've lost only one game since junior high, that to Manchester when they were freshmen.” Saylor also spoke of the team’s depth, as well as his only concerns. "We have three complete backfields which we can use. We've got Dan Salamin back at quarterback, with Greg Gutierrez and Mark Luma back at halfback. I'm concerned about complacency. I'm concerned about keeping everybody happy.”

''This is the group of kids we've been waiting for since they were in junior high. They've lost only one game since junior high, that to Manchester when they were freshmen.” Saylor also spoke of the team’s depth, as well as his only concerns. "We have three complete backfields which we can use. We've got Dan Salamin back at quarterback, with Greg Gutierrez and Mark Luma back at halfback. I'm concerned about complacency. I'm concerned about keeping everybody happy.”

A dominating 32-0 win over Blissfield in the season opener highlighted the strength of the defense. In game two, Clinton put up a good fight at Thompson Field, scoring two third quarter touchdowns to pull within two points, 16-14, but ultimately fell 32-14 as Luma rushed for 152 yards and two touchdowns on 21 carries. With the victory, Hudson now was tied with Pittsfield, Illinois, for second place nationally for consecutive wins at 64. Immediately, the spotlight on Hudson grew.

“I get at least two calls a day from newspapers, no less,” said Saylor at the time.

Hoping to see a repeat of the 1974 thriller, another huge crowd showed up for the Addison game. Hudson won the contest, 28-6, but took a huge blow with the loss of Luma early in the contest with torn ligaments in a knee.

Manchester, in week six, put up a bit of a struggle, but was defeated 18-7. Win number 70 was a convincing shutout of Bronson, 30-0. That set the stage for the Hillsdale game and a chance to tie the Jefferson City record.

The possibility of tying the mark was mentioned to a national television audience by former Detroit Lion Alex Karras on ABC’s Monday Night Football telecast. People magazine and Sports Illustrated were preparing stories for publication (Click to read the Sports Illustrated article). A camera crew from CBS sports, filming a spot for the Today Show, as well as numerous newspaper reporters had come to town. Coach Saylor fielded calls and requests for interviews from scores of radio and TV stations and newspaper and magazine reporters.

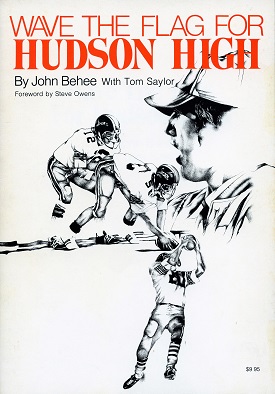

“The cheerleaders organized a special pep assembly, one that the community would never forget,” wrote John Behee in the book, Wave the Flag for Hudson High, detailing the streak. “Special invitations were extended to all of the 150 athletes who had played varsity football for Hudson High School during the eight-year victory string, to those who had performed as cheerleaders and to the parents of those players and cheerleaders.”

Telegrams from Jefferson City coach Pete Atkins and State of Michigan Governor William Milliken arrived before game time, wishing the team well. Luma, thought lost for the season, was cleared to play.

Ahead 11-0 at the half, the Tigers scored a 24-6 win over Class B Hillsdale to tie the mark. Writing for the Detroit News, Jerry Green recalled the theme song from an old radio adventure series, Jack Armstrong, All-American Boy, in his coverage of the game. The broadcast ran from 1933 to 1951.

"Wave the flag for Hudson High, boys, show them how we stand. Ever shall our team be champions, known through-out the land!"

“Jack Armstrong lives, a folk hero performing miracles … for Hudson High of course,” wrote Green. “He has gone into coaching and his name in true life is Tom Saylor.”

The only question that remained was whether playoff points would qualify the Tigers for the postseason. Based on strength of schedule and region, a loss by Allen Park Cabrini in its eighth and final week of football, and the upset of Traverse City St. Francis by Lansing Catholic Central in week nine improved the odds that the Tigers would earn a berth, but nothing was certain until final calculations by the MHSAA. The results were released late Sunday after the game.

According to the computer rankings, Hudson surpassed a 7-2 team from Flat Rock to represent Region II in the semifinal round of the postseason. They would play Region I’s Kalamazoo Hackett, once beaten during the regular season. The opportunity to capture the national record was scheduled for Saturday, Nov. 15 on the artificial turf of Houseman Field in Grand Rapids.

Again Gebhardt’s crew, along with 11,000 fans, caught the action. A fumble by Hackett on the first play from scrimmage was recovered by Hudson’s John Barrett and eight plays later, the Orange and Black were on the board. Gutierrez crashed through from the 1, followed by the 2-point conversion by Luma. The Tigers were up 24-6 at the half. Hackett scored midway through the third quarter to pull within 10, 24-14. From that point on, stellar defense on both sides defined the game. An interception by Hudson’s Tim Decker in the final minute of play sealed the win, and the country had a new record holder.

Congratulations flowed in from across America, and included a letter from President Gerald R. Ford, a former Michigan high school football player himself.

A week later, the ride ended in the state final game at Central Michigan University before a crowd of 7,000. Ishpeming opened up a 24-8 lead in the first quarter and downed the Tigers 38-22, grabbing the first MHSAA Class C title. The incredible streak was over. Gebhardt and his crew had captured grass roots America at its finest, including the storybook end.

“Mr. Steve Gebhardt,” wrote Behee, “who had shared intimately in the triumphs and heartbreaks of the 1975 football season was made an honorary 42nd member of the Hudson team and given a varsity letter for ‘guarding the water bucket.’”

The football team’s accomplishments continued to rack up honors. In January 1976, it was announced that Hudson would be honored with induction into the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame.

“This marks the first time in the Hall’s 22-year history that a team is to be honored, and I doubt if it happens again in our time.” said Nick Kerbawy, a former general manager of the Detroit Lions and the Detroit Pistons, and the Hall of Fame’s commissioner. “Many teams in Michigan have won consecutive championships, but no team — amateur or professional — can match Hudson’s amazing record.”

“This marks the first time in the Hall’s 22-year history that a team is to be honored, and I doubt if it happens again in our time.” said Nick Kerbawy, a former general manager of the Detroit Lions and the Detroit Pistons, and the Hall of Fame’s commissioner. “Many teams in Michigan have won consecutive championships, but no team — amateur or professional — can match Hudson’s amazing record.”

In 1976, Hudson again went undefeated, but because of the quirks of the early playoff system, failed to qualify for the postseason. The streak of regular-season victories was extended to 81 before ending in 1977.

Gebhardt began work, cutting down the hundreds of hours of film for the documentary. However, financing the project became a challenge.

“There is a terrific show here,” he would say, years later, describing his passion project. “The story up to the preparation after the Bronson game is pretty well cut. It's the fact that the story really is in the next three weekends of games. … It's that material after the Bronson game #70 that needs editing. (That is) where the meat of the story lives.”

“In the mid-1970s Mr. Gebhardt moved to Los Angeles and worked as an architect,” noted the New York Times. “He returned to Cincinnati in 1989 and resumed his film career.”

For the talented cameraman and story teller, other projects surfaced. A documentary on Bill Monroe, the father of bluegrass music, was released in 1993. A trio of films, with ties to the life of 1960s cultural activist John Sinclair, were filmed, edited and prepared for release.

Gebhardt’s passion for the Hudson High project was re-ignited in 1997 when California’s Concord De La Salle High School eclipsed the national mark, and again in 2008 when inquiries about the film were received.

In 2010, when Hudson defeated Ishpeming for the MHSAA Division 7 championship in a rematch of the 1975 title game, Gebhardt traveled from Cincinnati to Detroit’s Ford Field to film the meeting for possible use in the project.

Sadly, time expired. In October of this year, at the age of 78, Gebhardt passed away.

“At his death, he was at work on ‘Hudson Tigers,’ a documentary he began in the mid-1970s about a high school football team in Hudson, Mich., that had won 72 straight games,” stated his New York Times obituary.

“There are a number of versions of The Hudson Tigers out there,” wrote Gebhardt back in 2008, in an effort to attract financing for the tale. “All are of low resolution … quite frankly there isn't anyone other than me who can or should complete this show. What do you think?”

Despite a serious run at the mark by Ithaca High School, which assembled a 69-game streak that was ended by Monroe St. Mary Catholic Central in the 2014 Division 6 championship game, Hudson’s amazing feat of 72 straight remains the Michigan state record. So, too, stands the regular season mark of 81.

However, it remains to be seen if the work of a young filmmaker, on location 40 years ago to capture an amazing feat, ever sees the light of day. In this time of sports documentaries, will the flag for the Hudson High’s teams of 1968 to 1975 again be waved?

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

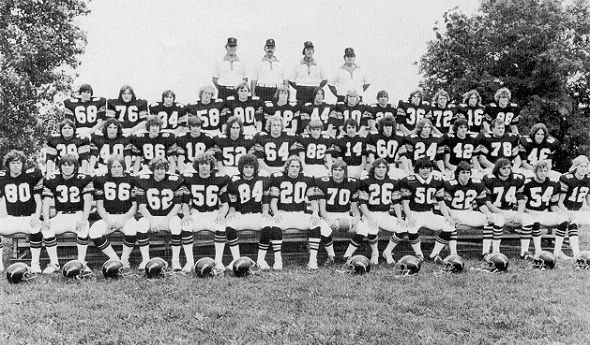

PHOTOS: (Top) The 1975 Hudson football team made the first MHSAA Playoffs; this is the team photo from the Finals program. (Top middle) John Behee wrote "Wave the Flag for Hudson High" about the record run. (Middle) Captains for Hudson, left, and Kalamazoo Hackett met at midfield before the 1975 Class C Semifinal. (Below middle) Sports Illustrated was among national media that wrote about the Tigers. (Below) A sign stands in Hudson saluting the success of the local football program. (Photos courtesy of Ron Pesch or taken from "Wave the Flag for Hudson High."