Moore Making Case as Best of Martin Luther King's QB Greats

By

Tom Markowski

Special for Second Half

October 7, 2021

It might come as no surprise to many, but we could be watching the best quarterback that's ever been a part of the rich football history at Detroit Martin Luther King.

Let's begin with Darnell Dickerson, an `86 King graduate. Dickerson was the Detroit News' No. 1 Blue Chip prospect and went on to play at Pittsburgh. More recently there's Dequan Finn, who led King to the 2016 Division 2 title. Finn is currently the back-up quarterback at Toledo.

Let's begin with Darnell Dickerson, an `86 King graduate. Dickerson was the Detroit News' No. 1 Blue Chip prospect and went on to play at Pittsburgh. More recently there's Dequan Finn, who led King to the 2016 Division 2 title. Finn is currently the back-up quarterback at Toledo.

Now there's Dante Moore. Moore (6-foot-3, 200 pounds) is still a junior, so there's still much for him to accomplish, and for us to witness, at King.

As a freshman, Moore led the Crusaders to the Division 2 title game before they lost to Muskegon Mona Shores, 35-26. Last season, King lost to River Rouge, 33-30, in a Division 3 Regional Final. This season, King is 5-1 and one of the favorites to win the Division 3 title. Its only loss was Carmel High, 42-40. Carmel (6-1) is one of the top teams in Indiana.

Tyrone Spencer is in his sixth season as King's head coach and he realizes, with Moore, he has a special player.

“He's very poised, mature for his age,” Spencer said. “He's a class act on and off the field. He's got a great arm and great accuracy.”

Moore, 16, attended a number of camps throughout the country this past summer including many in the South including at Auburn, Clemson, Florida State and Georgia. At the Elite 11 camp in California, Moore was able to gauge how he measures up to a number of the top quarterbacks in the country, many of whom are a year older, and he more than held his own.

In only four games on the field (two wins came by forfeit), Moore has completed 67 of 95 pass attempts, for 1,280 yards and 17 touchdowns. He's received 27 scholarship offers including from Michigan and Michigan State.

Despite all of the hype Moore has received, he remains grounded. He's a quiet leader, but a leader nonetheless. As a sophomore he was elected captain, a rarity for any program but especially one as successful as King.

“I remember my first snap (as a freshman) against Detroit Catholic Central at Wayne State,” he said. “It was crazy. Now I'm a junior, and I'm just thankful being with my teammates at a school like King.”

“I remember my first snap (as a freshman) against Detroit Catholic Central at Wayne State,” he said. “It was crazy. Now I'm a junior, and I'm just thankful being with my teammates at a school like King.”

Moore was King's starter from day one, and he remembers well that first game against DCC – a 24-22 defeat against the Shamrocks, who went on to share the Detroit Catholic League Central title.

“It was crazy, taking my first snap,” Moore said. “Now I'm a junior. It goes so fast.”

Life has its twists and turns, and Moore has had his share. Born in East Cleveland, Ohio, Moore and his family moved to Detroit when he was 5. His father grew up in the Detroit area and went to Southfield High, where he competed in basketball, football and track, and job opportunities brought Otha Moore and his family back to Detroit.

But before all that took place, Moore and his family had moved to Lorain, located just west of Cleveland, then they went to live with his grandmother on a farm in Lancaster, located just southeast of Columbus. Too young to be responsible for chores such as milking cows and such, Moore did get a taste of farm life and the early-to-bed, early-to-rise lifestyle.

In addition to football, Moore began playing soccer at an early age. From second grade through eighth Moore was on the pitch either as a goalkeeper or a striker. He credits that sport for improving his footwork. When asked if he'd play soccer if King sponsored the sport, Moore quickly replied yes and admits he misses the game. He does get a few opportunities to show those foot skills; Moore is King's punter and has handled the place-kicking duties at times.

There was a transitionary period, country life to the big city, but Moore said because he's the out-going type, it didn't take him long to make new friends. It was this type of personality that years later would lead to a relationship that would not only grow into a strong friendship, but one that would have a lasting effect on his development as a quarterback.

While working out at a Southfield health club, Moore recognized Devin Gardner – the former Inkster star and Michigan quarterback/receiver – going through his workout. Moore wasn't going miss out on this chance meeting. He introduced himself, and they almost instantly became friends. For the past three years or so, Gardner has worked with Moore, mostly during the offseason. But rarely does a week go by when the two don’t talk about football, school, you name it.

“We talk about anything,” Moore said. “We tell each other jokes. We go to fairs together. He gives me advice on how to be a better man in my life. He's making an impact. He gets me mentally prepared.”

Moore first acknowledges his father as the one who's had the greatest impact in his life – athletically, emotionally and socially. After that, it's his other family – the King coaching staff – who has played such an important part in his development.

First there's Spencer, then there's quarterback coach Jerrell Noland – a former King quarterback (2007 graduate) who played at Kentucky State – and Terel Patrick, King's offensive coordinator. Both Spencer and Patrick coached under one of the icons in Detroit's coaching history, James Reynolds, and Patrick like Noland also played for Reynolds.

“I lean on (Patrick's) shoulder,” Moore said. “He helps me break down film and be prepared. It's not all about football at King. It's family.”

As for college, Moore has placed those decisions on hold until after the season.

“I'm just thankful I have the opportunity to play at a school like King,” he said. “I'm concentrating on the season and winning a state title. At the end of the season, I'll narrow down my choices.”

Tom Markowski primarily covered high school sports for the The Detroit News from 1984-2014, focusing on the Detroit area and contributing to statewide coverage of football and basketball. He also is a former correspondent and web content director for State Champs! Sports Network. Contact him at [email protected] with story ideas for Oakland, Macomb and Wayne counties.

Tom Markowski primarily covered high school sports for the The Detroit News from 1984-2014, focusing on the Detroit area and contributing to statewide coverage of football and basketball. He also is a former correspondent and web content director for State Champs! Sports Network. Contact him at [email protected] with story ideas for Oakland, Macomb and Wayne counties.

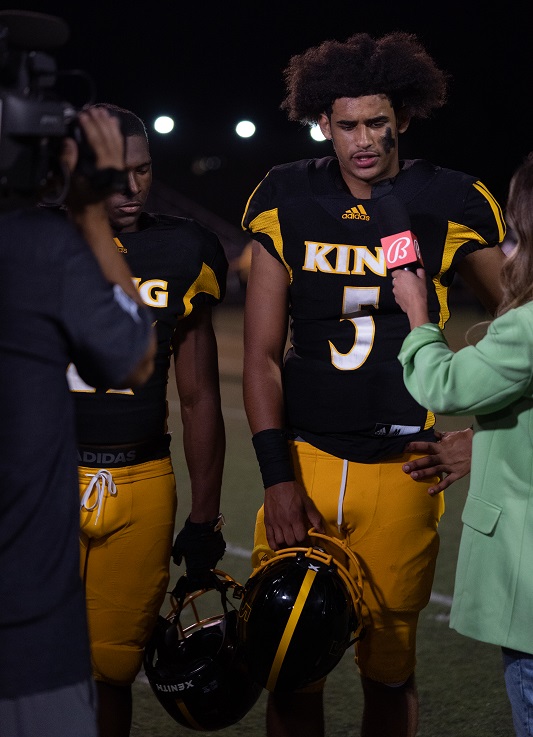

PHOTOS (Top) King quarterback Dante Moore (5) avoids the pressure during a 41-34 Week 3 win over Detroit Cass Tech. (Middle) Moore interviews after the game with Bally Sports Detroit. (Photos by Quintin Love Jr.)

Inspired by Dad's Memory, Lawrence's Vasquez Emerges After Family Losses

By

Pam Shebest

Special for MHSAA.com

January 16, 2024

LAWRENCE — While COVID-19 affected many students in different ways, it definitely made an impact on Austin Vasquez.

As a freshman at Lawrence High School during the pandemic, Vasquez lost his grandmother Theresa Phillips to cancer on March 25, 2021.

As a freshman at Lawrence High School during the pandemic, Vasquez lost his grandmother Theresa Phillips to cancer on March 25, 2021.

Two days later, on March 27, his father Tom Vasquez, died of complications from COVID. And on April 19 that spring, his grandfather Darrell “Gene” Phillips also lost his fight against the coronavirus.

“There is no way (to cope). You just have to keep on moving,” Austin said. “It’s what (my dad) would want me to do.

“He was my biggest (influence) in sports. He talked to me about never giving up – leave everything you’ve got.”

That is just what Vasquez is doing in the midst of his three-sport senior year.

He is the top wrestler at the school, competing at 175 pounds with a goal of making the MHSAA Tournament. He was a versatile contributor on the football field this past fall, and he’s planning to join the baseball team this spring.

He’s 8-3 with six pins on the mat this winter after a busy summer of camps and tournaments. Those experiences helped lessen the nerves he’d felt during matches previously, and now he’s wrestling with an outlook of “everything to gain and nothing to lose.”

He’s 8-3 with six pins on the mat this winter after a busy summer of camps and tournaments. Those experiences helped lessen the nerves he’d felt during matches previously, and now he’s wrestling with an outlook of “everything to gain and nothing to lose.”

And Vasquez said he feels his dad’s presence as he prepares for competition.

“Before every match, before every game, I just think about what my dad would be telling me,” he said. “Everything he’s always told me has taught me to get better.

“In life, I still remember everything he taught me. He was definitely a great man, and I want to be like him someday.”

Wrestling also has made Vasquez more in tune with his health.

His sophomore season he went from 230 pounds to 215, and by his junior year was down to his current 175.

“I just wanted to be healthier, not just for wrestling,” he said. “I started going to the gym every night, watched my calories, and from there grew (taller).

“Now I’m at 6-(foot-)2, and I don’t know how that happened,” he laughed.

Lawrence coach Henry Payne said Vasquez always has a positive attitude and helps the other wrestlers in the program.

“When he notices a kid next to him doing a move wrong, he’ll go over and show him the right way,” Payne said. “We have a lot of young kids that this is their first year, and he’s been a good coach’s helper.”

The coach’s helper gig will continue after graduation.

"Next year we’re hoping to open up a youth program here, and I got him and an alumni that graduated last year and is helping the varsity team this year (Conner Tangeman) to take over the youth program for us,” Payne said.

On the football team, Vasquez was a jack of all trades.

On the football team, Vasquez was a jack of all trades.

“He started at guard, went to tight end, went to our wingback, went to our running back. He was trying to get the quarterback spot,” football coach Derek Gribler laughed.

Vasquez said there is no other feeling like being on the field, especially during home games.

“Wrestling is my main sport, but I’d do anything to go back and play football again,” he said. “I just love it.”

Although the football team struggled through a 1-8 season, “It was still a really fun season,” Vasquez said. “Everybody was super close. Most of us never really talked before, but we instantly became like a family.”

Vasquez had the support of his mother, Heather, and four older sisters: Makaylah, Briahna, Ahlexis and Maryah. He also found his school family helped him get through the end of his freshman year.

“(My friends) were always there for me when everything was going on,” he said. “I took that last month off school because it was too hard to be around people at that time.

"Every single one of them reached out and said, ‘Hey, I know you’re going through a rough time.’ It really helped to hear that and get out of the house.”

The family connection between Vasquez and Lawrence athletic director John Guillean goes back to the senior’s youth.

The family connection between Vasquez and Lawrence athletic director John Guillean goes back to the senior’s youth.

“I was girls basketball coach, so I coached his sisters,” Guillean said. “I remember him when he was pretty young. I knew the family pretty well. I knew his dad. He was pretty supportive and was there for everything.”

Vasquez said that freshman year experience has made him appreciate every day, and he gives the following advice: “Every time you’re wrestling, it could be your last time on the mat or last time on the field. Treat every game and every match as if it’s going to be your last. If you’re committed to the sport, take every chance you have to help your team be successful.”

Gribler has known Vasquez since he was in seventh grade and, as also the school’s varsity baseball coach, will work with Vasquez one more time with the senior planning to add baseball as his spring sport.

“When we talk about Tiger Pride, Austin’s a kid that you can put his face right on the logo. His work ethic is just unbelievable,” Gribler said. “Everything he does is with a smile. He could be having the worst day of his life, and he’d still have a smile on his face. He pushes through. It’s tough to do and amazing to see.”

The coach – who also starred at Lawrence as an athlete – noted the small community’s ability to rally around Vasquez and his family. Lawrence has about 150 students in the high school.

“It goes beyond sports,” Gribler said. “Austin knows when he needs something he can always reach out and we’ll have his back, we’ll have his family’s back. It’s not so much about winning as it is about the kids.”

Vasquez is already looking ahead to life after high school. He attends morning courses at Van Buren Tech, studying welding, and returns to the high school for afternoon classes.

“I’d like to either work on the pipeline as a pipeline welder or be a lineman,” he said, adding, “possibly college. I would like to wrestle in college, but let’s see how this year goes.

“I’m ready to get out, but it’s going to be hard to leave this all behind.”

Pam Shebest served as a sportswriter at the Kalamazoo Gazette from 1985-2009 after 11 years part-time with the Gazette while teaching French and English at White Pigeon High School. She can be reached at [email protected] with story ideas for Calhoun, Kalamazoo and Van Buren counties.

Pam Shebest served as a sportswriter at the Kalamazoo Gazette from 1985-2009 after 11 years part-time with the Gazette while teaching French and English at White Pigeon High School. She can be reached at [email protected] with story ideas for Calhoun, Kalamazoo and Van Buren counties.

PHOTOS (Top) Lawrence senior Andrew Vasquez, right, wrestles against Hartford this season. (2) Vasquez works on gaining the advantage in a match against Mendon. (3) From left: Lawrence wrestling coach Henry Payne, athletic director John Guillean and football and baseball coach Derek Gribler. (4) Vasquez also was a standout on the football field. (Wrestling and football photos courtesy of the Lawrence athletic department. Headshots by Pam Shebest.)