Michigan's Most Vital Prep Sports Moment

April 30, 2018

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

Did you ever hear the one about an Ypsilanti lawyer, two girls from Ann Arbor – one 18 and one 17 – and a judge from Detroit?

I didn’t think so.

Well, pull up a chair. You might never look at a tennis ball, a pair of track cleats, or a softball in the same manner after this one.

Now this story goes back a bit. We’re talking 45, um, make that 46 years ago. It was handed down to me, so now I’m handing it down to you.

The girls, Cindy and Emily, had met at a tennis club when they were 11 or 12. Both were pretty good players who had done well at tennis tournaments before heading off to Huron High School. But there was concern that the girls wouldn’t have the chance to play truly competitive tennis while in high school. You see, like most public schools of the time, Huron had only one varsity tennis team, and that was filled with boys.

Contact was made with a friend and fellow tennis player to help guide things along when it came time to talk to the school board about the girls joining that team.

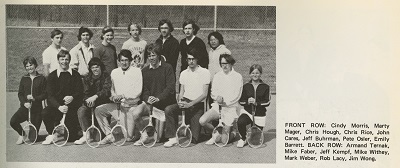

The conversation between that tennis friend – Larry the Lawyer – and the school board went pretty well. The board decided to let the girls play on the boys tennis team provided they could pass the tryouts. Well, as you’ve probably surmised, the girls did all right. With the blessing of Coach Jerry, it was decided Cindy and Emily would play No. 2 doubles for the River Rats.

But as we all know, such decisions aren’t always met with cupcakes being served and happiness. People don’t always like change.

But as we all know, such decisions aren’t always met with cupcakes being served and happiness. People don’t always like change.

And that was pretty much the case here.

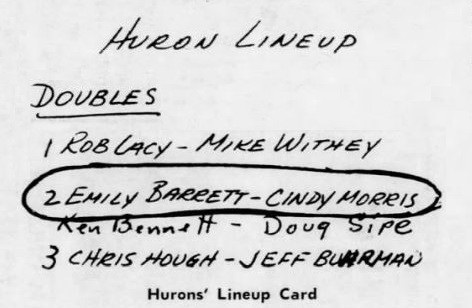

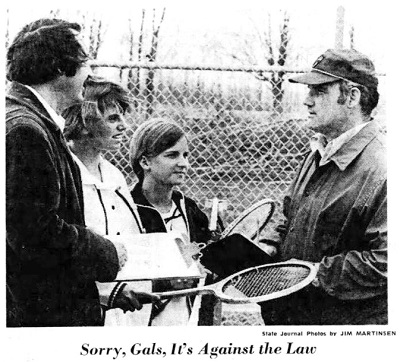

State officials didn’t much care for the idea. You see, when it came to interscholastic athletics, according to state rules established in 1967, girls couldn’t play on boys teams. Still, the Huron tennis team made the 60-mile trip up to Lansing on a Wednesday in April for a match with Lansing Harry Hill High School. Coach Jerry met with Hill’s coach, they shook hands, then Coach Jerry turned in his line-up card, to make things orderly and official.

Since there were girls names on the lineup card, not a single ball was served that day. Folks figured this was going to be the case. So the players and the bus turned around and headed back to Ann Arbor. Hill claimed a forfeited match because of that rule.

That set wheels in motion. Larry the Lawyer declared that this was a clear case of discrimination and a violation of Cindy and Emily’s right to equal protection under the 14th Amendment. With that, a lawsuit quickly was filed.

Now, they say that this was one of the first, if not the first lawsuits about such things. And you must remember this all happened back in early 1972, before the arrival of Title IX.

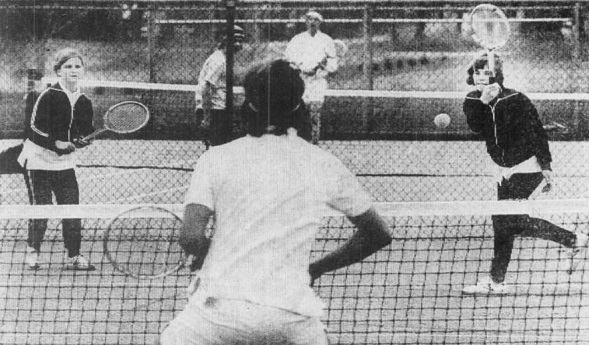

Turns out, Larry and the girls won their case. In Federal District Court, Judge Keith listened to what was said and issued a preliminary injunction allowing the girls to play. A little later in the week, Emily and Cindy won their first varsity doubles match hosted in Battle Creek, much to the dismay of their male opponents.

The next month, the Michigan Legislature adopted a bill allowing girls to compete on male teams, but only in non-contact sports. In late May, the doubles team of Emily and Cindy defeated a doubles team from Harry Hill, 6-3, 6-1.

The next month, the Michigan Legislature adopted a bill allowing girls to compete on male teams, but only in non-contact sports. In late May, the doubles team of Emily and Cindy defeated a doubles team from Harry Hill, 6-3, 6-1.

Of course, as with many of these rulings, there was an appeal. And, as these things usually do, it took a while to move this along. But come January 1973, the U.S. Circuit Court down in Cincinnati agreed with Judge Keith and upheld the preliminary injunction. They, too, thought that girls should be able to participate in varsity interscholastic sports. The Circuit Court did narrow Judge Keith’s decision a bit, inserting the word “NON-CONTACT” into the ruling. Suddenly, it was officially OK for girls to play alongside the boys in sports like tennis, swimming, archery, golf, bowling, fencing, badminton, gymnastics, skiing, and track and field.

Now just because there’s a law, it doesn’t mean everyone’s abiding by it. It would take several more years and the threat or the filing of additional lawsuits against school districts and organizations to truly see things change.

Today, we don’t think twice when we take a seat at a girls softball game, track meet or tennis match. But a short time ago, such things simply did not exist for our daughters. The actions of two girls from Ann Arbor, an Ypsilanti lawyer and a judge from Detroit altered the athletic world – for the better.

Lawrence Sperling’s lawsuit to support Cindy Morris’ and Emily Barrett’s quest to play high school sports was certainly a highlight of his career as an attorney. Lawrence and his wife Doris had sons who were outstanding tennis players. Michael and Gene were high-ranking players at Ann Arbor Pioneer during the 1970s. Gene played four years of tennis at the University of Minnesota and would later serve as Director of the National Economic Council and Assistant to the President for Economic Policy under Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. In 2012, he would write about his father and the landmark case for the White House.

Lawrence Sperling’s lawsuit to support Cindy Morris’ and Emily Barrett’s quest to play high school sports was certainly a highlight of his career as an attorney. Lawrence and his wife Doris had sons who were outstanding tennis players. Michael and Gene were high-ranking players at Ann Arbor Pioneer during the 1970s. Gene played four years of tennis at the University of Minnesota and would later serve as Director of the National Economic Council and Assistant to the President for Economic Policy under Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. In 2012, he would write about his father and the landmark case for the White House.

Judge Damon Keith had been appointed to the bench of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan by President Lyndon Baines Johnson, in 1967. It was some four and a half years later that the Morris-Barrett complaint landed on his docket. A graduate of Detroit Northwestern High School, he is the father of three daughters. Keith would later be appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit Court in Cincinnati by President Jimmy Carter in 1977. In 1995, he became the Senior Judge of that court. His amazing story was later told in a documentary “Walk With Me: The Trials of Damon J. Keith.”

Judge Damon Keith had been appointed to the bench of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan by President Lyndon Baines Johnson, in 1967. It was some four and a half years later that the Morris-Barrett complaint landed on his docket. A graduate of Detroit Northwestern High School, he is the father of three daughters. Keith would later be appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit Court in Cincinnati by President Jimmy Carter in 1977. In 1995, he became the Senior Judge of that court. His amazing story was later told in a documentary “Walk With Me: The Trials of Damon J. Keith.”

According to media reports, Coach Jerry Shull had been trying to get girls eligible for the previous two seasons, but felt the ultimate solution was to have high schools around the state form all-girls varsity teams. He again served as varsity tennis coach in 1973 (of a team that featured 10 females) before stepping aside in 1974.

Emily Barrett was a multi-sport athlete at Huron High School, competing with the Girls Athletic Club in swimming, field hockey and volleyball as well as tennis during this era of transition. During her senior year, the courts finalized their decision and she again played tennis for Huron. She’d move on to Denison University in Granville, Ohio, after graduation, where she played tennis and field hockey.

Emily Barrett was a multi-sport athlete at Huron High School, competing with the Girls Athletic Club in swimming, field hockey and volleyball as well as tennis during this era of transition. During her senior year, the courts finalized their decision and she again played tennis for Huron. She’d move on to Denison University in Granville, Ohio, after graduation, where she played tennis and field hockey.

A year older than Barrett, Cindy Morris had graduated from Ann Arbor Huron High School by the time the case was finalized. She headed off to the University of Michigan and then transferred to Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, where she played No 1. singles and doubles and twice participated in the National Collegiate Women’s Tournament. She later earned her Master’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University. As Cindy Morris, a sports journalist for the Cincinnati Enquirer, she recalled the words of Judge Keith for an article she was writing in late summer of 1978.

“Indeed, no male could have matched (the) soprano cries of joy when Judge Keith said, yes, go out and run and play and win and lose and laugh and cry and feel that special pride of playing for your school that boys in Michigan have always felt but you haven’t.”

The article was about a lawsuit originating in Yellow Springs, Ohio, where a girl was fighting to be allowed to compete in contact sports against boys.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS: (Top) The first high school match in 1972 for Ann Arbor Huron's Emily Barrett, left, and Cindy Morris was reported on for the Battle Creek Enquirer. (Top middle) The 1972 Ann Arbor Huron varsity tennis team, including Morris and Barrett. (Middle) The Ann Arbor Huron lineup card shows Barrett and Morris' names for a match against Lansing Harry Hill that was not played. (Below) A Lansing State Journal clipping tells of Hill electing to not play the match.

- Field Hockey

- Boys Soccer

- Girls Swim & Dive

- Boys Tennis

- Girls Tennis

- Girls Volleyball

- Girls Cross Country

- Boys Cross Country

- Football

- Girls Golf

- MHSAA News

Field Hockey Debut, Tennis Finals Change Among Most Notable as Fall Practices Set to Begin

By

Geoff Kimmerly

MHSAA.com senior editor

August 8, 2025

The addition of girls field hockey as a sponsored postseason championship sport and a revised schedule for Lower Peninsula Boys Tennis Finals are the most significant changes to fall sports as practices are set to begin Monday, Aug. 11, for an anticipated 100,000 high school athletes at Michigan High School Athletic Association member schools.

The fall season includes the most played sports for both boys and girls; 36,210 football players and 19,679 girls volleyball players competed during the Fall 2024 season. Teams in those sports will be joined by competitors in girls and boys cross country, field hockey, Lower Peninsula girls golf, boys soccer, Lower Peninsula girls swimming & diving, Upper Peninsula girls tennis and Lower Peninsula boys tennis in beginning practice next week. Competition begins Aug. 15 for cross country, field hockey, golf, soccer and tennis, Aug. 20 for swimming & diving and volleyball, and Aug. 28 for varsity football.

Field hockey is one of two sports set to make its debut with MHSAA sponsorship during the 2025-26 school year; boys volleyball will play its first season with MHSAA sponsorship in the spring.

There are 37 varsity teams expected to play during the inaugural field hockey season. There will be one playoff division, with the first MHSAA Regionals in this sport beginning Oct. 8 and the first championship awarded Oct. 25.

To conclude their season, Lower Peninsula boys tennis teams will begin a pilot program showcasing Finals for all four divisions at the same location – Midland Tennis Center – over a two-week period. Division 4 will begin play with its two-day event Oct. 15-16, followed by Division 1 on Oct. 17-18, Division 2 on Oct. 22-23 and Division 3 played Oct. 24-25.

Also in Lower Peninsula boys tennis, and girls in the spring, a Finals qualification change will allow for teams that finish third at their Regionals to advance to the season-ending tournament as well, but only in postseason divisions where there are six Regionals – which will be all four boys divisions this fall.

The 11-Player Football Finals at Ford Field will be played this fall over a three-day period, with Division 8, 4, 6 and 2 games on Friday, Nov. 28, and Division 7, 3, 5 and 1 games played Sunday, Nov. 30, to accommodate Michigan State’s game against Maryland on Nov. 29 at Ford Field.

Two more changes affecting football playoffs will be noticeable this fall. For the first time, 8-Player Semifinals will be played at neutral sites; previously the team with the highest playoff-point average continued to host during that round. Also, teams that forfeit games will no longer receive playoff-point average strength-of-schedule bonus points from those opponents to which they forfeited.

A pair of changes in boys soccer this fall will address sportsmanship. The first allows game officials to take action against a team’s head coach in addition to any cautions or ejections issues to players and personnel in that team’s bench area – making the head coach more accountable for behavior on the sideline. The second change allows for only the team captain to speak with an official during the breaks between periods (halftime and during overtime), unless another coach, player, etc., is summoned by the official – with the penalty a yellow card to the offending individual.

A few more game-action rules changes will be quickly noticeable to participants and spectators.

- In volleyball, multiple contacts by one player attempting to play the ball will now be allowed on second contact if the next contact is by a teammate on the same side of the net.

- In swimming & diving, backstroke ledges will be permitted in pools that maintain a 6-foot water depth. If used in competition, identical ledges must be provided by the host team for all lanes, although individual swimmers are not required to use them.

- Also in swimming & diving – during relay exchanges – second, third and fourth swimmers must have one foot stationary at the front edge of the deck. The remainder of their bodies may be in motion prior to the finish of the incoming swimmer.

- In football, when a forward fumble goes out of bounds, the ball will now be spotted where the fumble occurred instead of where the ball crossed the sideline.

The 2025 Fall campaign culminates with postseason tournaments beginning with the Upper Peninsula Girls Tennis Finals during the week of Sept. 29 and wrapping up with the 11-Player Football Finals on Nov. 28 and 30. Here is a complete list of fall tournament dates:

Cross Country

U.P. Finals – Oct. 18

L.P. Regionals – Oct. 24 or 25

L.P. Finals – Nov. 1

Field Hockey

Regionals – Oct. 8-21

Semifinals – Oct. 22 or 23

Final – Oct. 25

11-Player Football

Selection Sunday – Oct. 26

District Semifinals – Oct. 31 or Nov. 1

District Finals – Nov. 7 or 8

Regional Finals – Nov. 14 or 15

Semifinals – Nov. 22

Finals – Nov. 28 and 30

8-Player Football

Selection Sunday – Oct. 26

Regional Semifinals – Oct. 31 or Nov. 1

Regional Finals – Nov. 7 or 8

Semifinals – Nov. 15

Finals – Nov. 22

L.P. Girls Golf

Regionals – Oct. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, or 11

Finals – Oct. 17-18

Boys Soccer

Districts – Oct. 8-18

Regionals – Oct. 21-25

Semifinals – Oct. 29

Finals – Nov. 1

L.P. Girls Swimming & Diving

Diving Regionals – Nov. 13

Swimming/Diving Finals – Nov. 21-22

Tennis

U.P. Girls Finals – Oct. 1, 2, 3, or 4

L.P. Boys Regionals – Oct. 8, 9, 10, or 11

L.P. Boys Finals – Oct. 15-16 (Division 4), Oct. 17-18 (Division 1), Oct 22-23 (Division 2), and Oct. 24-25 (Division 3)

Girls Volleyball

Districts – Nov. 3-8

Regionals – Nov. 11 & 13

Quarterfinals – Nov. 18

Semifinals – Nov. 20-21

Finals – Nov. 22

The MHSAA is a private, not-for-profit corporation of voluntary membership by more than 1,500 public and private senior high schools and junior high/middle schools which exists to develop common rules for athletic eligibility and competition. No government funds or tax dollars support the MHSAA, which was the first such association nationally to not accept membership dues or tournament entry fees from schools. Member schools which enforce these rules are permitted to participate in MHSAA tournaments, which attract more than 1.4 million spectators each year.