MHSAA Neck Guard Requirement Rooted in 1999 'Impossible to Forget' Injury

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

February 3, 2022

Dan DiCristofaro has made it a mission to remind schools, coaches, athletic directors, and other officials of the need to enforce an equipment rule, added to the MHSAA hockey rule book more than 20 years ago.

“Officials are not trying to give out misconduct penalties,” wrote DiCristofaro in a recent email, “but the avoidance by so many players to wear this piece of equipment as intended in its unaltered state or to even wear a neck guard at all has become almost the norm instead of the exception.”

“This is mandatory,” emphasized the long-time hockey official during a recent conversation. “It’s required, not recommended. Required.”

As a witness to an unforgettable occurrence during a game, DiCristofaro wants others to do what they can to reduce the odds of that moment happening again.

Rivals

The Wednesday, Feb. 10, 1999, game between Trenton and Redford Catholic Central was a rematch – the second game of a home-and-home series that had been played for years. Two of the state’s hockey powerhouses, the foes were certainly familiar with each other.

“The rivalry between Trenton and Catholic Central has probably gone on since the 60s,” recalled Trenton coach Mike Turner.

“They were usually two of the best teams in the state,” added Gordon St. John, Catholic’s coach at the time.

“They were usually two of the best teams in the state,” added Gordon St. John, Catholic’s coach at the time.

Both coaches were speaking in 2010, for REPLAY, a sports television series created by Gatorade, built around the re-staging of games between high school rivals. Fox Sports Net broadcast the game.

“If you go into our gymnasium, you will find 42 state banners,” noted Fr. Richard Ranalletti, principal at CC from 2000 to 2010. “Thirteen of them are in hockey” (1959, 1961, 1968, 1974, 1994, 1997, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2009). Founded in 1928, Detroit Catholic Central had moved to Redford Township 50 years later. (The campus moved again in 2005, this time to Novi.)

The city of Trenton was founded in 1834. A 1901 report in the Free Press speaks of architect Edward C. Leyen completing plans “for a high school building for the board of education of Trenton.”

“Since 1975, there’s 12 state championship banners (1976, 1979, 1980, 1982, 1986, 1991, 1996, 1998, 2003, 2004, 2008, 2009) hanging in our arena,” said Jerry Brown, Mayor of Trenton in his interview for the program.

Hank Minckiewicz, sports editor for the News-Herald in Trenton, summed it up: “Back in 1999, there was not a bigger rivalry in the state than Trenton and Catholic Central.”

Fifth-ranked Trenton had downed No. 1 CC, 1-0, at Redford Arena earlier in the 1999 season – the Shamrocks’ only loss at that point in the annual chase for a state title. The second game between the schools was played at Trenton’s Kennedy Recreation Center, then a single rink arena, before a full house. Catholic Central opened a 4-1 lead before the Trojans, dressed in their home white jerseys, stormed back to tie the game at 4-4 with about five minutes to play.

Nightmare Come to Life

The moment on the ice, caught on videotape, appears harmless enough.

“Late in the game, a Trenton player knocked a CC player off balance, sending his leg back into the air.” recounted Bill Roose in the Detroit Free Press, describing the freak accident that nearly took the life of Trojans senior Kurt LaTarte.

A 6-foot defenseman, LaTarte had been near the play and initially continued toward the puck, but then circled back and headed to the Trenton bench.

Lori Holcomb, a team trainer for Trenton, recalled the moment for REPLAY, documenting the night.

“Kurt was coming on to the bench, and he was kind of holding the side of his face and his neck and he said, ‘The kid’s boot hit me in the chin … I think my chin is cut.’

‘It was clean and straight,” she continued, “like surgical.”

It wouldn’t remain that way.

Guardian Angels

“The gash across the right side of his neck was four inches long and two inches wide,” wrote Roose in touching on the horror that quickly unfolded.

Chaos erupted on the Trenton bench as the color of LaTarte’s jersey changed from white to red.

“The game was so intense. … It was so jam-packed with people,” remembered DiCristofaro. “You couldn’t even hear yourself because it was so loud. We did not know that this had happened during the game until a linesman who happened to be standing next to the bench saw what was going on. … He’s the one who blew his whistle loud and kept blowing it for the play to actually stop.

“Once it all hit home and the play stopped … everybody went stone silent. Once everybody knew what was happening and everybody was informed, the players started kneeling, a lot of them were crying.”

The game was ended.

“Fortunately,” stated Roose, “(there were) a few guardian angels among the … spectators.”

Dr. David Wolf, nurse Leslie Zancanaro and firefighter Alec Lesko were all at the game because they had sons on Trenton’s team.

Wolf would accompany LaTarte to the hospital, “detailing his injuries to emergency room doctors” at Oakwood/Seaway Hospital in Trenton. Surgery that night repaired vein and muscle damage. On Friday, he was released from University of Michigan Hospitals in Ann Arbor. A week later, LaTarte was back in school.

In a follow-up article in the Free Press, the LaTarte Family thanked all involved with saving Kurt’s life.

DiCristofaro had officiated the game.

The Injury

Regrettably, this was far from the first time a hockey player had suffered such an injury. While certainly not common, and not always fatal, cuts like these are extremely serious. And for all involved – from spectator to player – impossible to forget.

Simply put, carotid arteries carry oxygenated blood to the head, face, and brain through the neck, while the jugular veins passing through the neck handle deoxygenated blood. Disruption to these vessels can quickly create major precarious problems instantly.

Few hockey fans can forget the horrific story of Clint Malarchuk, goalie for the Buffalo Sabres of the National Hockey League, nearly “bleeding to death on the ice when a skate severed his jugular vein,” in 1989. Many had forgotten that a similar injury to carotid arteries occurred to NHL player Jackie Leclair of the Montreal Canadians in 1954. (It would happen again in 2008, this time to Richard Zednick of the Florida Panthers). There have been various near misses and close calls in the NHL and professional hockey’s minor leagues.

Reports of cuts to the neck in Canada appeared in both U.S. and Canadian newspapers, including one causing the death of a 29-year-old father of two, Maurice Ayotte, who was playing amateur hockey in December 1973.

In another instance, a team trainer and a teammate were credited with saving the life of Kim Crouch of the Markham, Ontario Waxers in January 1975. An 18-year-old junior league goalie, he had been cut while making a save. The near tragedy inspired Kim’s father, Edward M. Crouch, to design a neck protector.

“Maybe this neck guard will prevent other boys from going through what he did,” Edward told The Canadian Press. “It’s a combination of a baby’s bib and a turtleneck sweater.”

“Maybe this neck guard will prevent other boys from going through what he did,” Edward told The Canadian Press. “It’s a combination of a baby’s bib and a turtleneck sweater.”

By the fall of 1976, the initial “Kim Crouch Safety Collar” – weighing 3½ ounces and made of Nylon Ballistic Material and closed-cell foam – was available in stores. Two years later, it was being worn by several NHL and minor league goalies, and within five years, other manufacturers had throat protectors on the market.

Yet, their existence didn’t ensure broad acceptance or use.

It would take a series of tragic episodes that occurred within a span of two years to alter equipment requirements for youth hockey above the border.

In December 1983, a Montreal, Quebec boy, James Lechman, who played for the Class BB Rosemont team, died. Down on the ice in a scramble in front of his team’s net, the Rosemont goalie’s skate accidentally clipped the 15-year-old’s neck while he tried to block a shot.

In October 1984, Henry Reimer of the Richmond, British Columbia Sockeyes, a 17-year-old “standout centre” in the B.C. Junior Hockey League, survived a throat slit suffered when a teammate fell prior to a game during warmups, and his skate clipped Reimer. Fifty stitches – “30 internal and 20 external” – were required to close the wound. “Only the swift action of trainers and ambulance attendants prevented a tragedy,” stated the Vancouver, B.C. Province.

“If it was millimetres, either way,” Sockeyes’ coach Vic LeMire would later say, “he would be a statistic.”

A month later, Stephane Saint-Aubin, an 18-year-old Repentigny Olympiques player in the Junior AA Quebec league, died due to a similar injury. It was his first game with the team.

CCM and Cooper released new or redesigned versions of protectors that covered the neck and upper chest in 1985. Following his injury, Reimer, who would play college hockey on scholarship for the University of Illinois, worked with a Michigan company to develop another design.

But in September 1985, misfortune struck again within the same B.C. Junior Hockey League. Abbotsford British Columbia Falcons forward Jeff Butler, another 18-year-old, died after being cut on the throat by the “freshly sharpened, razor-sharp” blade of a teammate’s skate, according to another Province report.

The exhibition game, played before a crowd of just 200, was called off after the incident, midway through the second period. Doctors had labored to save Butler’s life but were unsuccessful.

“There are not words to describe what happened,” said coach Larry Romanchych to the Vancouver Sun.

Romanchych, who had previously played with Chicago and Atlanta in the NHL, immediately went to work searching for neck protectors. After examining the various types available, he purchased Crouch Collars.

“After what happened Saturday. I will never let my own (12-year-old) son on the ice without one,” vowed Romanchych. “And I will never let anybody who plays for me go without one. (The players) will get used to them, the same way we got used to playing with helmets. It’s just a shame that something … has to happen before we do anything about it.”

New Requirement

Some leagues in Canada took action and began to require players and goalies to wear neck guards. Players complained, stating the guards were uncomfortable and/or too hot to wear, and the rules were not always enforced. Heartbreaking accidents continued to occur.

The Canadian Standards Association (CSA)/Bureau de Normalisation du Quebec (BNQ) began work to establish guidelines for protection to be met by manufacturers. The injury to Malarchuk (an Alberta, Canada native) would ensure the passage of a national directive.

Still, it took time.

Challenges arose for manufacturers to distribute products to Canada’s more than 400,000 players, especially to small cities. That presented some implementation delays, but as of Jan. 1, 1994, it was a requirement to wear a Canadian Standards Association-approved throat protector (sometimes referred to as a neck laceration guard) labeled or stamped with the initials BNQ for all participants across the Canada Amateur Hockey Association.

Another death, this time in Sweden in 1995, moved the country to require all hockey players to wear neck guards.

Back in Michigan

“Neck guards are mandatory for youth hockey players in Canada,” wrote Anjali J. Sekhar days after LaTarte’s injury in an article for the Port Huron Times-Herald. “And while they are not mandatory in the United States, many people believe it’s common sense to wear them.”

While recognizing that the piece of equipment did not guarantee tragedy would always be avoided, the MHSAA still responded promptly to what had happened in Trenton. In May 1999, the MHSAA’s Representative Council, following Canada’s lead, instituted a mandatory neck guard rule for scholastic athletes in 2000.

Like our northern neighbors, the equipment worn by players must bear a label from BNQ. Today, the MHSAA is one of only two high school governing bodies in the United States to require hockey neck guards.

REPLAY by Gatorade

In May 2010, Gatorade reunited former members of the 1999 game from both DCC and Trenton, including LaTarte, their teams’ original coaching staffs, and two of the three officials from the game for a full-check, regulation-length replay of the contest. (Ironically, only weeks before, both schools had won MHSAA hockey titles.)

“For Trenton hockey alumni, redemption has come after years of waiting as they defeated their Detroit Catholic Central counterparts by a score of 4-2,” stated a news release following the contest.

“From the moment Compuware Arena's doors opened, to the ceremonial puck-drop by game day commissioner, ‘Mr. Hockey®’ Gordie Howe, to the final horn sounding, excitement filled the arena. The teams, which hit the ice in front of nearly 4,000 people, were joined by Detroit hockey legends Scotty Bowman and Brendan Shanahan who provided their expertise and guidance as honorary coaches to the Catholic Central and Trenton squads, respectively.”

“From the moment Compuware Arena's doors opened, to the ceremonial puck-drop by game day commissioner, ‘Mr. Hockey®’ Gordie Howe, to the final horn sounding, excitement filled the arena. The teams, which hit the ice in front of nearly 4,000 people, were joined by Detroit hockey legends Scotty Bowman and Brendan Shanahan who provided their expertise and guidance as honorary coaches to the Catholic Central and Trenton squads, respectively.”

Prior to the game, training for former players had lasted eight weeks.

“We’re thinking this game was going to be more fun and ceremonial and casual,” said DiCristofaro, laughing at the memory. “The first few minutes shocked us with the physicality. This was serious hockey.

“These guys are running at each other. They were 17 and 18 years old again. There were some serious body checks. We had to start intervening immediately before somebody got hurt.

“They really went all-out with training and practice and off-ice conditioning to get ready for this game.”

“I knew this was an awesome opportunity to get the teams together and close this chapter,” said LaTarte. “Seeing how this came together, it was definitely worth every ounce of sweat.”

Prompting the Memory

Sadly, these memories of the happy ending were prompted by another much more recent nightmare. This January, once again, the razor-blade sharpness of an unintended air-bound ice skate took a life, this time in Connecticut. The player was Teddy Balkind, a 16-year-old sophomore at St. Luke’s School in New Canaan. The contest was with Brunswick School, located in Greenwich. In a letter written by Mark Davis, St. Luke’s head of school, to school families and reported in the media, he clarified details of the accident, misreported by some of the media:

“Teddy did not fall and was not lying on the ice. He was skating upright and low. During the normal course of play, another player’s leg momentarily went into the air and, through no fault of anyone’s, or any lack of control, his skate cut Teddy.”

Recommend, but not Require

“’Commercially manufactured throat guards designed specifically for ice hockey are required for all players, including goaltenders during regular season and tournament play,’ Connecticut Interscholastic Athletic Conference rules state,” noted the Toronto Star in coverage. “St. Luke’s and Brunswick play in the Fairchester Athletic Association, which like most prep school conferences follows the policy of USA Hockey and the NCAA, which recommend rather than require neck guards.”

“Founded on Oct. 29, 1937, in New York City … the organization was known as the Amateur Hockey Association of the United States (AHAUS) and changed to its present name in June 1991. While youth hockey is a main focus, USA Hockey also has vibrant junior and adult hockey programs that provide opportunities for players of all ability levels. The organization also supports a growing disabled hockey program.”

The Player Safety and Health Information page on USA Hockey’s website, while recommending neck laceration protectors and expressing concern about such injuries, stated (as of Feb. 3, 2022), “There is sparse data on neck laceration prevalence, severity and neck laceration protector (neck guard) effectiveness.”

“USA Hockey recommends that all players wear a neck laceration protector, choosing a design that covers as much of the neck area as possible. Further research & improved standards testing will better determine the effectiveness of neck laceration protectors.”

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

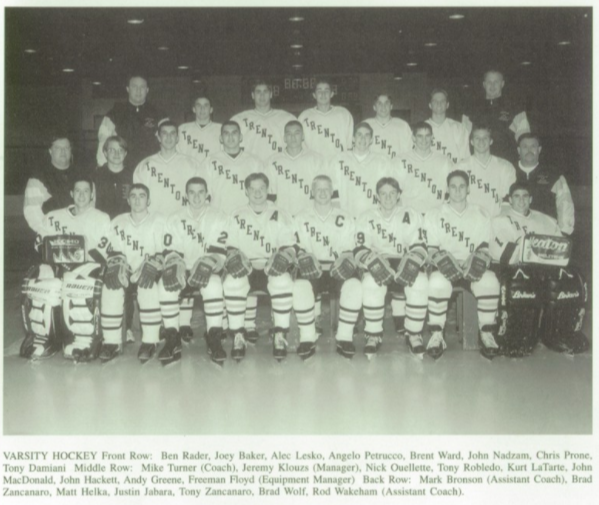

PHOTOS (Top) The neck guard worn by this player may have prevented injury as another skater toppled in front of the goal. (2) The 1999 Trenton hockey team. (3) The Kim Crouch Safety Collar was the first neck guard of its kind. (4) The 1999 Detroit Catholic Central hockey team. (Top photo by Judy Gill; other photos collected by Ron Pesch.)

Be the Referee: Puck on Goal Netting

By

Paige Winne

MHSAA Marketing & Social Media Coordinator

December 9, 2025

Be The Referee is a series of short messages designed to help educate people on the rules of different sports, to help them better understand the art of officiating, and to recruit officials.

Below is this week's segment – Puck on Goal Netting - Listen

We’re on the ice today, where after being last touched by Team A, the puck comes to rest on top of the goal netting. What happens?

New this year in high school ice hockey: If a puck is on the top of the goal netting, it’s an immediate stoppage. The puck is considered out of play.

It goes back into play via a faceoff from the nearest faceoff dot in the defending team’s zone.

Why the change from previous years? Because a puck on top of the netting creates too many problematic scenarios to be considered playable – you could have high sticking, closed hand (handling of the puck), goalkeeper contact or player-in-the-goal-crease.

If the puck is on top of the goal netting, blow the whistle and resume with a faceoff.

Previous 2025-26 editions

Dec. 2: Goaltending vs. Basket Interference - Listen

Nov. 25: Football Finals Instant Replay - Listen

Nov. 18: Volleyball Libero Uniforms - Listen

Nov. 11: Illegal Substitution/Participation - Listen

Nov. 4: Losing a Shoe - Listen

Oct. 28: Unusual Soccer Goals - Listen

Oct. 21: Field Hockey Penalty Stroke - Listen

Oct. 14: Tennis Double Hit - Listen

Oct. 7: Safety in Football - Listen

Sept. 30: Field Hockey Substitution - Listen

Sept 23: Multiple Contacts in Volleyball - Listen

Sept. 16: Soccer Penalty Kick - Listen

Sept. 9: Forward Fumble - Listen

Sept. 2: Field Hockey Basics - Listen

Aug. 26: Golf Ball Bounces Out - Listen

PHOTO Marquette's Skyler Blackburn and Negaunee goalie Kurt O'Brien scramble for the puck during a Nov. 8 matchup. (Photo by Randy Ritari.)