Health & Safety: A Look Back, Gallop Ahead

By

John E. (Jack) Roberts

MHSAA Executive Director, 1986-2018

August 7, 2015

We are just completing year six of eight during which we have been addressing the four important health and safety issues that, for ease of conversation, we call the “Four Hs.”

During the 2009-10 and 2010-11 school years, our focus was on Health Histories. We made enhancements in the pre-participation physical examination form, stressing the student’s health history, which we believe was and is the essential first step to participant health and safety.

During the 2011-12 and 2012-13 school years, our focus was on Heads. We were an early adopter of removal-from-play and return-to-play protocols, and our preseason rules/risk management meetings for coaches included information on concussion prevention, recognition and aftercare.

Without leaving that behind, during the 2013-14 and 2014-15 school years, our focus was on Heat – acclimatization. We adopted a policy to manage heat and humidity – it is recommended for regular season and it’s a requirement for MHSAA tournaments. The rules/risk management meetings for coaches during these years focused on heat and humidity management.

At the mid-point of this two-year period, the MHSAA adopted policies to enhance acclimatization at early season practices and to reduce head contact at football practices all season long.

Without leaving any of the three previous health and safety “H’s” behind, during the 2015-16 and 2016-17 school years, our focus will be on Hearts – sudden cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death.

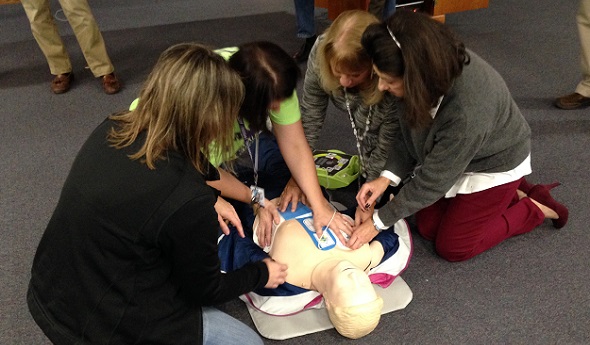

Coinciding with this emphasis is the requirement that all high school level, varsity level head coaches be CPR certified starting this fall. Our emphasis will be on AEDs and emergency action plans – having them and rehearsing them.

On Feb. 10, bills were introduced into both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, together called the “Safe Play Act (see below),” which addressed three of the four health and safety “H’s” just described: Heat, Hearts and Heads.

For each of these topics, the federal legislation would mandate that the director of the Centers for Disease Control develop educational material and that each state disseminate that material.

For the heat and humidity management topic, the legislation states that schools will be required to adopt policies very much like the “MHSAA Model Policy to Manage Heat and Humidity” which the MHSAA adopted in March of 2013.

For both the heart and heat topics, schools will be required to have and to practice emergency action plans like we have been promoting in the past and distributed to schools this summer.

For the head section, the legislation would amend Title IX of the 1972 Education Amendments and eliminate federal funding to states and schools which fail to educate their constituents or fail to support students who are recovering from concussions. This support would require multi-disciplinary concussion management teams that would include medical personnel, parents and others to provide academic accommodations for students recovering from concussions that are similar to the accommodations that are already required of schools for students with disabilities or handicaps.

This legislation would require return-to-play protocols similar to what we have in Michigan, and the legislation would also require reporting and recordkeeping that is beyond what occurs in most places.

This proposed federal legislation demonstrates two things. First, that we have been on target in Michigan with our four Hs – it’s like they read our playbook of priorities before drafting this federal legislation.

This proposed federal legislation also demonstrates that we still have some work to do.

And what will the following two years – 2017-18 and 2018-19 – bring? Here are some aspirations – some predictions, but not quite promises – of where we will be.

First, we will have circled back to the first “H” – Health Histories – and be well on our way to universal use of paperless pre-participation physical examination forms and records.

Second, we will have made the immediate reporting and permanent recordkeeping of all head injury events routine business in Michigan school sports, for both practices and contests, in all sports and at all levels.

Third, we will have added objectivity and backbone to removal from play decisions for suspected concussions at both practices and events where medical personnel are not present; and we could be a part of pioneering “telemedicine” technology to make trained medical personnel available at every venue for every sport where it is missing today.

Fourth, we will have provided a safety net for families who are unable to afford no-deductible, no exclusion concussion care insurance that insists upon and pays for complete recovery from head injury symptoms before return to activity is permitted.

We should be able to do this, and more, without judicial threat or legislative mandate. We won’t wait for others to set the standards or appropriate the funds, but be there to welcome the requirements and resources when they finally arrive.

Safe Play Act — H.R.829

114th Congress (2015-2016) Introduced in House (02/10/2015)

Supporting Athletes, Families and Educators to Protect the Lives of Athletic Youth Act or the SAFE PLAY Act

Amends the Public Health Service Act to require the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to develop public education and awareness materials and resources concerning cardiac health, including:

- information to increase education and awareness of high risk cardiac conditions and genetic heart rhythm abnormalities that may cause sudden cardiac arrest in children, adolescents, and young adults;

- sudden cardiac arrest and cardiomyopathy risk assessment worksheets to increase awareness of warning signs of, and increase the likelihood of early detection and treatment of, life-threatening cardiac conditions;

- training materials for emergency interventions and use of life-saving emergency equipment; and

- recommendations for how schools, childcare centers, and local youth athletic organizations can develop and implement cardiac emergency response plans.

Requires the CDC to: (1) provide for dissemination of such information to school personnel, coaches, and families; and (2) develop data collection methods to determine the degree to which such persons have an understanding of cardiac issues.

Directs the Department of Health and Human Services to award grants to enable eligible local educational agencies (LEAs) and schools served by such LEAs to purchase AEDs and implement nationally recognized CPR and AED training courses.

Amends the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 to require a state, as a condition of receiving funds under such Act, to certify that it requires: (1) LEAs to implement a standard plan for concussion safety and management for public schools; (2) public schools to post information on the symptoms of, the risks posed by, and the actions a student should take in response to, a concussion; (3) public school personnel who suspect a student has sustained a concussion in a school-sponsored activity to notify the parents and prohibit the student from participating in such activity until they receive a written release from a health care professional; and (4) a public school's concussion management team to ensure that a student who has sustained a concussion is receiving appropriate academic supports.

Directs the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to develop public education and awareness materials and resources to be disseminated to schools regarding risks from exposure to excessive heat and humidity and recommendations for how to avoid heat-related illness. Requires public schools to develop excessive heat action plans for school-sponsored athletic activities.

Requires the CDC to develop guidelines for the development of emergency action plans for youth athletics.

Authorizes the Food and Drug Administration to develop information about the ingredients used in energy drinks and their potential side effects, and recommend guidelines for the safe use of such drinks by youth, for dissemination to public schools.

Requires the CDC to: (1) expand, intensify, and coordinate its activities regarding cardiac conditions, concussions, and heat-related illnesses among youth athletes; and (2) report on fatalities and catastrophic injuries among youths participating in athletic activities.

2016 Bush Awards Honor Valued Educators

By

Geoff Kimmerly

MHSAA.com senior editor

June 20, 2016

Three educators who have combined for more than a century of service to high school athletics – Adrian Madison’s Kristen Isom, Holly’s Deb VanKuiken and Battle Creek’s Jim Cummins – have been named recipients of the Michigan High School Athletic Association's Allen W. Bush Award for 2016.

Al Bush served as executive director of the MHSAA for 10 years. The award honors individuals for past and continuing service to prep athletics as a coach, administrator, official, trainer, doctor or member of the media. The award was developed to bring recognition to men and women who are giving and serving without a lot of attention. This is the 25th year of the award, with selections made by the MHSAA's Representative Council.

“This year’s three Bush Award winners are tied by their dedication to working with our student-athletes on a day-to-day basis over the course of decades, providing guidance that in turn has been spread throughout their local and sport communities,” said John E. “Jack” Roberts, executive director of the MHSAA. “We are grateful for their service and pleased to honor them with the Bush Award.”

Isom, a member of the MHSAA’s Representative Council since 2008, recently completed her 30th year of service and currently is athletic director at Madison for grades 7-12. She’s also taught health and physical education and coached at least one of a variety of sports every year. She’s served as president of the Tri-County Conference for the last decade after previously serving as secretary and treasurer.

An MHSAA tournament host for many events over the years, Isom was named Region 6 Athletic Director of the Year in 2000 from the Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Administrators Association. She’s a member of that association, the National Interscholastic Athletic Administrators Association and the Society of Health and Physical Educators of Michigan. The class adviser at Madison for this fall’s juniors, Isom also assists in selection for the MHSAA Student Advisory Council.

An MHSAA tournament host for many events over the years, Isom was named Region 6 Athletic Director of the Year in 2000 from the Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Administrators Association. She’s a member of that association, the National Interscholastic Athletic Administrators Association and the Society of Health and Physical Educators of Michigan. The class adviser at Madison for this fall’s juniors, Isom also assists in selection for the MHSAA Student Advisory Council.

A graduate of Clinton High School, Isom earned her bachelor’s degree from Michigan State University, a master’s from Eastern Michigan University and has completed graduate courses from Fresno Pacific University. She’s active with Adrian’s United Church of Christ in various service projects, including an annual fundraiser for cancer research.

“As her community has grown over the years, and the needs and expectations have evolved for all of our schools, Kris Isom has provided valuable leadership at both the local and statewide levels,” Roberts said. “Her many contributions have been rooted in her belief in the mission of educational athletics. Her work with students at her school and input on selections for our Advisory Council show again her dedication to those learning those lessons by playing our games. She’s a worthy recipient of the Bush Award.”

VanKuiken also just completed her 30th year in education, including her 18th as an athletic administrator. She’s served as athletic director for Holly Area Schools the last 12 years after teaching at Bridgeport from 1984-1996 and then serving as assistant principal and athletic director at that school from 1996-2002. She coached softball, volleyball and both boys and girls tennis at various points during her time at Bridgeport, girls tennis as the varsity head coach from 1985-95. She also served as secretary and then president of the Tri-Valley Conference while at Bridgeport. Holly has added high school boys and girls bowling and middle school softball, baseball, swimming & diving and bowling during her tenure.

The Region 9 Athletic Director of the Year in 2007, VanKuiken was elected to the MIAAA Executive Board in 2005 and served as president during the 2007-08 school year. She helped produce a “Critical Incident Plans” DVD for the association to assist administrators statewide and created the first strategic plan for the MIAAA during her term as president. She received the MIAAA’s George Lovich Service Award in 2011.

The Region 9 Athletic Director of the Year in 2007, VanKuiken was elected to the MIAAA Executive Board in 2005 and served as president during the 2007-08 school year. She helped produce a “Critical Incident Plans” DVD for the association to assist administrators statewide and created the first strategic plan for the MIAAA during her term as president. She received the MIAAA’s George Lovich Service Award in 2011.

VanKuiken also has served on the board of directors for The Academy of Sports Leadership, which plans and organizes camps for future coaches every summer in Ann Arbor, and is a member of the NIAAA, serving on its endowment committee. After a three-sport career at Lansing Sexton, he earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Central Michigan University and played field hockey collegiately, and she’s attained Certified Master Athletic Administrator status from the NIAAA. She received the MHSAA’s Women in Sports Leadership Award in 2009.

“Deb VanKuiken’s work shows she always has the athlete in mind, from the opportunities she’s worked to add through new programs at her school to the programs she’s initiated as a leader of the MIAAA,” Roberts said. “Her vision continues to benefit all groups she serves, not only athletes, but coaches and administrators as well. We’re pleased to recognize her with the Bush Award.”

Like VanKuiken, Cummins also coached a number of sports at the high school level and primarily tennis; he coached that sport for 47 years in addition to baseball, football, basketball for 33 years and volleyball for 11. At Battle Creek Springfield and Battle Creek Central, he coached 67 Regional tennis champions and four flights that won individual Finals titles. His teams finished third at MHSAA Finals four times and won eight straight Kalamazoo Valley Association titles.

He’s perhaps most recognizable statewide for directing more than 40 MHSAA Tennis Finals for either boys or girls at various sites around the Lower Peninsula. He’s also managed an MHSAA Regional every year since 1974 for boys and all but three years since 1983 for girls, and has continued to serve on the MHSAA seeding and rules committees.

He’s perhaps most recognizable statewide for directing more than 40 MHSAA Tennis Finals for either boys or girls at various sites around the Lower Peninsula. He’s also managed an MHSAA Regional every year since 1974 for boys and all but three years since 1983 for girls, and has continued to serve on the MHSAA seeding and rules committees.

Cummins was twice named Class C/D Coach of the Year, once for boys season and once for girls, by the Michigan High School Tennis Coaches Association, and he was inducted into that association’s Hall of Fame in 1990. He also is a member of the Colon and Battle Creek Public Schools halls of fame and received the MHSTeCA’s Distinguished Service Award in 2014. Cummins graduated from Colon in 1963 and Central Michigan in 1967. He retired from public education after 30 years and currently is employed as an adjunct instructor of mathematics by Kellogg Community College. He was named Outstanding Educator by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation in 1990, 1992, 1994, 1995 and 1999.

“Jim Cummins’ impact on athletes and coaches over many years have turned into positive effects on hundreds as his lessons have been passed on,” Roberts said. “He has been especially valuable to the MHSAA as a knowledgeable voice in tennis and a tournament host in that sport at our highest level, and he’s also lent his time and expertise to our volleyball and wrestling tournaments over the years. We’re glad to honor Jim Cummins with the Bush Award.”

The MHSAA is a private, not-for-profit corporation of voluntary membership by more than 1,400 public and private senior high schools and junior high/middle schools which exists to develop common rules for athletic eligibility and competition. No government funds or tax dollars support the MHSAA, which was the first such association nationally to not accept membership dues or tournament entry fees from schools. Member schools which enforce these rules are permitted to participate in MHSAA tournaments, which attract more than 1.4 million spectators each year.