Coaches: Making a Difference

By

Rob Kaminski

MHSAA benchmarks editor

February 8, 2013

“A coach can never make a great player of a youngster who isn't potentially great.

But a coach can make a great competitor of any child.

And miraculously, coaches can make adults out of children.

For a coach, the final score doesn't read so many points for my team; so many points for theirs.

Instead it reads:

So many men and women out of so many boys and girls.

And this is a score that is never published.

And this is a score that coaches read to themselves, and in which they find real joy ...

When the last game is over.”

—Anonymous

The author of this poem prefers to be left anonymous, but there are those in the MHSAA office who know the person behind the words. And, they know the words were genuine, coming from a former long-time high school coach who believed in those values and lived them.

In today’s ever-changing world, one wonders if all coaches would be better off going about their tasks anonymously. In the fall issue of benchmarks, we shined a spotlight on a group whose highest compliment is to go about their business unnoticed: the contest officials.

This series celebrates those who don’t have that luxury. In communities across the country, large and small, rural and urban, everyone seems to know the names of their high school coaches. And, the cost of such infamy comes with heavy taxes these days, levied by societal shifts whereby an increasing number of parents and children perceive playing time, starting roles and connections to big-time colleges as natural-born rights.

Punch “high school coach firings” into Google, and you’ll get close to 13 million results. Upon inspecting a healthy sampling of these stories, some dismissals are due to misconduct – criminal or otherwise – but you’ll find far greater instances involving parental meddling and win-loss records.

More alarming is this: in related topics at the bottom of the first search page, “how to get a high school coach fired” appears. A click on that little gem returns more than 21 million results, including such sub-searches as “how can parents legally fire a high school basketball coach” and “how to get rid of a high school coach.” Might be enough to make a person want to officiate.

Unfairly, the public measure of coaches too often does not go beyond the scoreboard. Sadly, the fates of these educators hinge upon the performance of people not old enough to vote or, in many cases, drive.

And yet, coaching positions continue to be among those most coveted in many communities. What is it about the profession? What drives these individuals? Thankfully, our fields and gyms continue to be filled with leaders who don’t overemphasize wins and losses; who exude fairness and sportsmanship; who simply aim to teach lessons to students the way any math or science teacher would. People who care about your children.

By and large, the reason is because they had the right experiences with the right coaches when they were younger.

“My swim coach (Darin Millar, Royal Oak HS) was a major factor in why I entered education and coaching,” said David Zulkiewski, who is in his 13th year of paying it forward as coach of the boys and girls swim teams at Bloomfield Hills Andover. “I went to a private all boys school (Warren DeLaSalle) and the Christian Brothers provided a great role model for me that aided in my decision to become a teacher/coach. I saw the sacrifices they made and how hard they worked to help students and athletes.”

It’s in the makeup of coaches to dive head first into the profession, which is really a continuous cycle that begins when today’s crop of coaches were in their heyday as athletes.

“Participating in athletics created some of my best high school memories,” said Middleville Thornapple-Kellogg cross country coach Tamara Benjamin. “After college, when I had the chance to begin coaching, I jumped at it. I felt it was an honor and a privilege to coach a high school team, and 25 years later I still feel the same way.”

For still others, the exposure to coaching came even earlier, as they experienced the way of life on a daily basis.

“My father was a high school coach of football and basketball. I was in the gym a lot growing up and it became a goal of mine to become a coach also,” said Diane Laffey, the winningest softball coach in MHSAA history, and No. 5 on the girls basketball list in her 50th year at Warren Regina. “I saw how he cared for his players off the court as well as on and it made me believe that perhaps I could make a difference in an athlete’s life.”

Pressures and challenges

There are, no doubt, many coaches who wish all parents would have been coaches, at least for one day. Perhaps then, there would be a greater understanding of what the job entails on a daily basis, and maybe even some empathy from a group which often causes far more headaches than even the most inexperienced playing roster.

A recent survey of more than 3,000 coaches nationwide identifies parents as the biggest challenge to the daily tasks of today’s athletic mentors (See the story on page 15 of this issue),

The study revealed that nearly 50 percent of the respondents identified over-involved parents as the No. 1 concern, while 80 percent of the subjects perceived that a child’s playing time was the parents’ No. 1 issue with today’s coaches.

“Parents, seem to be more and more demanding of your time and commitment, a street that does not travel both ways,” said Don Kimble, now in his 24th year as the swimming & diving coach at Holland High School.

“The biggest problem with our job is parents,” said Mike Roach, bowling coach at Battle Creek Pennfield. “With the proximity of spectators to athletes in bowling, its hard to get them to understand that as coaches it is our job to coach and their job to cheer. Some have taught their kids and now have a hard time letting the coach do his or her job.”

Part of the issue also stems from the parents’ perception of their kids’ best sports.

“It seems like many sports are now becoming year-round activities instead of seasonal. I think it’s very important that children play a variety of sports instead of specializing when they are young. I think parents owe it to their child to have them try several sports or activities to find which one their child likes, not the one the parent likes,” said Rockford hockey coach Ed Van Portfliet.

“It seems like many sports are now becoming year-round activities instead of seasonal. I think it’s very important that children play a variety of sports instead of specializing when they are young. I think parents owe it to their child to have them try several sports or activities to find which one their child likes, not the one the parent likes,” said Rockford hockey coach Ed Van Portfliet.

The pressures to specialize can come from other sources, too, often times coming from within the walls of the school. Despite the bad rap parents can get, the majority do have their child’s best interests in mind. In many cases, they respect and listen to a coach’s advice. At times, in fact, coaches are their own worst enemies.

“In many schools I think pressure to specialize comes from the respective coaches. I try to keep a lid on it at Regina – but I know that some of our girls do specialize,” said Laffey, who also is the school’s athletic director. “I encourage them to play more than one sport; and a lot of our athletes do that. I emphasize to our coaches that these girls are high school students and they should be allowed to participate in as many extracurriculars as possible.

“I think the travel club teams and AAU in many sports is hurting high school athletics. Student-athletes are being asked to specialize too early.”

Abby Kanitz, just 28 years old and a neophyte in the coaching business compared to Laffey, has seen too much of it already. As if to prove her stance on multi-sport participation, Kanitz has been the competitive cheer coach at Thornapple-Kellogg for six years, and recently added track and field duties to her resume’.

“There should be no specialization,” said Kanitz. “A student-athlete who has the opportunity to be an athlete in college will not lose that opportunity by participating in other sports. I think the pressure comes from coaches, sadly. Parents – if the coach is respected – listen to coaches and take the opinion and feedback to heart. If we are encouraging our athletes to experience more than one sport in high school, chances are their parents will, too.”

That type of pressure, real or perceived, can lead to the athletes puttting restrictions on themselves.

“In the past things were simpler. There weren’t as many demands on our athletes. There weren’t as many options and distractions,” said Gary Ellis, boys tennis coach and athletic director at Allegan. “There was less specialization – if you could, you went from one sport to the next and enjoyed the one you were playing at the time.”

Dave Emeott, 18-year boys track & field coach, and 7-year cross country coach at East Kentwood, agrees.

“When I was in high school I participated in four sports my senior year,” he said. “These days the three-sport athlete is as rare as a popular referee. I completely understand the shift to specialization and being competitive, but I sure had a lot of fun with all my teammates and would not trade it for any improved performances.”

The increase in perceived importance of community-based sports has also led to heightened tunnel-vision when it comes to an athletes and their parents choosing his or her path.

In the worst-case scenarios, the youth programs are headed by non-school coaches who lack accredited training and do not share the same educational philosophies of the school coaches. Parents also susceptible to heeding the advice of these coaches, and the results can be disastrous.

“I believe as school coaches we need to be more involved in youth sports; we understand our programs and how to develop young people,” said James Richardson, wrestling coach of 22 years at Grand Haven High School. “Parent volunteers in our youth programs are extremely important, but most are not educators. The parents need to be educated and made aware of our expectations as much as our student-athletes.”

At such an impressionable time in their lives, athletes in the youth sports realm learn from everyone in the setting, from teammates to coaches to spectators. Not all of the lessons are positive.

“Ultimately we want all athletes to become good citizens and athletics is an excellent avenue for this. If you have ever spent a few minutes in the bleachers at a youth sporting event, you will soon realize we have a long way to go,” said Emeott. “If the fans of these events are who our young athletes are learning citizenship and proper behavior from, then we need to consider spending more of our practice time at all levels teaching citizenship to our athletes, and maybe even to our parents.”

To remedy these situations, greater ties are needed between the school system and community youth programs.

“We need more adult volunteers to help coach and teach our youth in a positive manner,” said Cathy Mutter, competitive cheer coach at Munising for the past 21 years. “We have many opportunities in Munising for students to participate in a variety of sports and activities. The programs are very valuable to the youth of our community. It keeps them active and involved in organized activities. They learn the rules and regulations of the sports they are participating in and the value of teamwork.”

Emeott adds, “I think, at a minimum, each organization should have an extensive parent code of conduct. A parent code of conduct could help educate the parents of our future athletes.”

Mike Van Antwerp, in his ninth year at the helm of the boys lacrosse program at Holt also coaches youth soccer while running a couple summer lacrosse leagues, and can see room for improvement.

“Youth sports should foster teamwork, fun, work ethic, thinking and processing skills as well as respect for the game,” Van Antwerp said. “In many environments it is working, but it depends on the program and the coaches. The focus has to be on teaching the game, not winning the game.”

In some case, it’s becoming increasingly expensive to play the games. The pay-to-play phenomenon is a pothole that most of today’s coaches didn’t have to dodge when they were in high school. Some districts apply a blanket fee to participate in all sports, while others are sport-by-sport, in some cases making the student chose one sport over another.

“We ended pay to play about six years ago, thankfully,” said Ellis. “When we had it, numbers dropped significantly. Those who were tennis players, played. The drop was in those who wanted to ‘try it,’ so it limited the number of new players.”

The use of participation fees to help fund interscholastic athletics in Michigan high schools has doubled during the last nine years, although the percentage of schools assessing them has held steady over the last two, according to surveys taken by the MHSAA.

The most recently completed survey indicates that of 514 member schools responding, 260 schools – 50.5 percent – charged participation fees during the 2011-12 school year.

Yet, in speaking with those directly affected, it’s simply part of the job; almost an afterthought. Simply add another fund raiser in some shape or form.

“We have fundraisers, and I wish we didn’t. They take so much time and effort,” said Jim Niebling, who has organized his share in 23 years as Portland’s boys tennis coach and 18 as the girls mentor. “Our most successful fund raisers have been charity poker events, and ushering at MSU’s Breslin Center.”

Several schools sponsor the typical pop can fund raisers, while Richardson tosses in a couple new wrinkles with mulch sales and a pig roast to help fatten the coffers for his program.

At Portland, the fee is $125 per student, per school year, and in some ways, Niebling thinks it might even be a positive influence.

“The amount is low enough and it’s for a whole year,” Niebling said. “So if anything, it may have even increased participation in some activities so parents could feel that they ‘got their money’s worth.’”

In the cases of newer MHSAA sports such as bowling and lacrosse, generating funds is just a carryover from the days when the schools sponsored club sports.

“We have always been self-funded and it is a challenge to raise money in-season, so we try to do it out of season,” said Kimberly Vincent, Grand Haven girls lacrosse coach for six years. “I work with kids to help them reduce their costs; earn money on the side and with used equipment.”

Fellow lacrosse coach Van Antwerp notes that the annual cost to participate in his sport is nearly $400, but he’s seen no marked decrease in roster size.

Athletics is no different than other sectors of society; not all team rosters offer the same demographic makeup. As such, some sports have been hit a little harder in recent years.

“My husband and I are proprietors and we helped to get high school bowling off the ground when our son was in high school,” said Marshall boys and girls bowling coach Sue Hutchings. “The school charges $50 pay-to-participate. Our bowling program charges $65. It has impacted us more this year due to financial problems in our district. We always work through the situation on a case-by-case basis.”

For others, geographic location can put hardships on students and the budget that other schools can’t fathom.

“There are eight competitive cheer teams in the entire Upper Peninsula. We have to travel almost every weekend at least six hours one way to a meet/competition,” Mutter said. “The time the athletes spend out of school and on the road is challenging physically and academically. The cost adds up as well. With school budget cuts and families struggling to make ends meet, it is a huge burden at times.”

Mutter works as the school nurse for the Munising district, so in that regard, she does have some advantages over many leaders in her sport, which has a fair share of non-faculty coaches. By nature, those who are employed within a school district enjoy some inherent benefits compared to non-faculty personnel.

“The biggest issue is practice times,” said Brenda McDonald, Grand Rapids Kenowa Hills/ Grandville gymnastics coach for 14 years. “I cannot go right after school like many other sports and sometimes that is hard on the girls with homework and other areas.”

Peter Militzer is the boys and girls tennis coach at Portage Central, for 21 and 18 years, respectively. By day, he’s the tennis director at the YMCA of Greater Kalamazoo. By nature, he is partial to tennis, but still champions the cause for multi-sport participation.

“Coaches and parents need to stop pushing kids into one exclusive sport,” Militzer said. “Our athletic director (Jim Murray) pounds the ‘well-rounded athlete’ idea into our heads at every staff meeting. During the off-season I don’t personally work with tennis players or apply pressure on them to only play tennis. I don’t think sport specialization is necessary for athletic success.”

He’d like to be around his players more, but only for familiarity purposes, a yearning many non-faculty coaches share.

“Not having access to players and their info during the day is the greatest challenge I face not being in the building,” Militzer said. “I am fortunate to work with a great athletic director and his assistant, and they keep me in the loop.”

Being kept in the loop is one of the primary challenges facing non-faculty coaches, who often times are well apprised of contest rules, but might not be as familiar with MHSAA regulations.

Brian Telzerow, a youth ministry professor at Kuyper College who coaches boys golf at Forest Hills Northern and girls golf at Forest Hills Eastern, makes a concerted effort to work closely with the schools, saying, “I have to be very intentional in communication with and from the school.”

Grand Haven’s Vincent, a marketing communications professional, echoes the sentiment.

“We are not in the loop of communications, network and friendships. Our kids miss out on some opportunities because of it,” Vincent said. “For instance, the use of special equipment, facilities, and other benefits available to other teams with coaches who are at the school. We have to go onsite to pick up our mail, it is not forwarded to us.”

The gap can at times cause lapses in important communication from the MHSAA for those least familiar with some of the Association’s regulations. Most coaches have preseason meetings for players where rules and regulations are discussed, but it is important that all the right messages are being relayed to team members and parents.

“From the outsider’s perspective I would imagine the MHSAA’s greatest challenge is to empower athletic directors with the knowledge to make the correct decisions for our athletes and coaches,” Emeott said. “The MHSAA can only be as good as the individual school districts.”

Kimble, who is Holland Aquatic Center’s supervisor of competitive swimming in addition to his high school coaching duties, adds that school support can be an issue in certain sports as well.

“Communication as well as off-site involvement of the non-swimming community within the school can create challenges,” Kimble said. “Since our pool is also not part of the campus, not many students and/or faculty attend swim meets, or have even been to the pool.”

Plentiful rewards

Yet, for all the pitfalls and hurdles, coaches are at peace with who they are; and they know that there are others who would take their jobs in a heartbeat. That’s what keeps them in it the most. It’s feelings like this:

- “I coach life more than I coach golf. We teach every day of our lives by the way we live and what we say. Teaching is more of a lifestyle than a job. It is truly a privilege to walk with students through some of their most formative years.” – Telzerow

- “Working with so many high school girls and seeing them succeed in life is probably the most rewarding thing to me. To see many of them go into the coaching field makes me feel that I have done some things right to make them want to coach.” – Laffey

- “I think the most rewarding moments are when we witness real change in a young adult. As coaches, we have a view like no other. We watch a gangly, immature freshman walk into the gym, and a grown adult walk out.” – Emeott

- “Coaching is helpful in teaching as every person on your team has a role, and understanding the differences of young people and what they can contribute to your program makes coaches find ways to incorporate these same methods into the classroom.” – Richardson

- “I have made lasting friendships with coaches and judges from all over the state. I have attended many weddings and baby showers for former athletes.” – Mutter

- “Teaching and coaching are one in the same. The goal in both situations is to help the student develop as an individual; to develop good life skills and attitudes. Athletics provides opportunities that do not exist in the classroom: developing leadership skills and teamwork.” – Ellis

- “It goes beyond just winning games. It’s seeing the growth and development of the young men I’ve coached. It’s seeing them overcome difficulties to reach goals. It’s seeing the academic successes and the accomplishments after they leave our program.” – Van Portfliet

- “On a more personal level, I’ve been able to witness the positive impact the sport has had on many kids, whether it’s them working extremely hard to make a contribution to the team, or their success creating new options for them in terms of school.” – Van Antwerp

- “The most rewarding moments are the small things: an athlete new to the sport suddenly ‘getting it;’ a parent in tears because their child is so happy at what he or she is doing; an athlete who says. ‘Thanks for being a good coach.’” – Hutchings

- “Athletics is second to school. When you teach and coach, you truly understand the reason. It’s not about being eligible, it’s about teaching your athletes proper priorities – school comes first.” – Kanitz

- “The most rewarding moments are when former players stay in touch with you. Next most rewarding is when I see a former player who tells me they still enjoy playing tennis. I’ve coached team state champions, and individual state champions, but those brief moments don’t compare.” – Militzer

- “I’ve been to hundreds of grad parties, weddings, family gatherings, baptisms, etc. I feel honored that these kids and young adults take the time to include me in their lives. Notes and letters I continue to receive from past athletes are very humbling.”– Benjamin

This story is not about strategies, Xs and Os, or gameplans. All of these coaches are fierce competitors who are driven to win. But they are fueled by something deeper.

“I played tennis for Harley Pierce Sr. He was eventually named to the high school football and tennis coaches halls of fame, plus he was named the national tennis coach of the year in the early 1980s,” said Niebling. “I didn’t appreciate him then as much as I did a few years later when I became a teacher/coach. Only after being out of high school and then coaching myself did I realize what in influence he had on me.”

As alluded to in the poem to open this story, that is the real score.

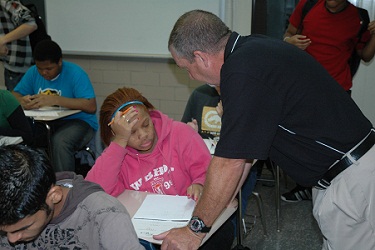

PHOTOS: (Top) Warren Regina coach Diane Laffey, speaking with her players, is the winningest coach in MHSAA softball history and also among the winningest for girls basketball. (Middle) Grand Haven wrestling coach James Richardson, speaking with one of his athletes, has led that program for 22 years.

A Day in the Life of High School Sports

November 29, 2011

A pile of shoes clutters a doorway. A man teaches algebra to 9th-graders who have the weekend on their minds. A woman screenprints another T-shirt in her basement. A man brooms dead flies from a countertop.

Riverting scenes, for sure.

Yet, people around Michigan pay $5 for these, and other activities on a routine basis, weekend after weekend, during the school year without knowing it. Until now.

Join us for a day (or two) in the life of high school sports.

Introducing the cast

Carly Joseph’s cross country race doesn’t begin in the starting box. Eric Hartley’s whistle to signal the opening kickoff doesn’t begin his day. Vicky Groat doesn’t start coaching her volleyball team with the first serve. And Leroy Hackley’s daily duties do not begin by turning the key to the football stadium gate.

These are moments the spectators wait for; why they pay admission. But, the events are just the end product – and a miniscule part – of a daily intersection of paths, people and preparation played out in scenes like these throughout every community in the state on any given day.

Vicky Groat

Athletic Director

Varsity Volleyball Coach

Battle Creek St. Philip HS/

St. Joseph Middle School

Vicky recently finished her 14th season as the Tigers’ volleyball coach and is in her fourth year as athletic director for both the high school and middle school. She’s a 1985 graduate of St. Philip, and played volleyball for her mother, Sheila Guerra, who coached the Tigers to nine MHSAA titles. Like Guerra, Groat is a member of the MIVCA Hall of Fame, and has coached six MHSAA?Class D championship teams. She played volleyball and basketball at Kellogg Community College before finishing her studies at Central Michigan.

Eric Hartley

MHSAA Football Official

Math Department Head,

Lansing Everett HS

Eric is a 1980 Lansing Everett grad who earned teaching degrees at Western Michigan University and Michigan State University and began teaching math at Everett in 1986. He has been the math department head for 12 years and teaches four classes with one planning period. After a brief foray into coaching, Eric became a registered football and basketball official in 1990, and worked MHSAA?Football Finals in 1994, 1998 and 2002.

Leroy Hackley

Athletic Director

Jenison HS

Leroy is in his seventh year as athletic director at Jenison, following five years in the same position at Byron Center HS. He heads a department which sponsors 23 sports. In a school of 1,475 students, 45 percent participate in at least one sport. Leroy also was an MHSAA?registered official for 27 years, and still officiates collegiate basketball.

Carly Joseph

Junior, Class of 2013

Pontiac Notre Dame Prep

Carly is three-sport athlete at Notre Dame Prep and a member of the MHSAA?Student Advisory Council. She runs cross country and pitched on last spring’s District-winning softball team. Her third sport is unique in the high school setting. Carly started the school’s competitive school snowboarding team, and spends the winter competing against other high school students in boarder cross. Carly is also involved in NDP’s Varsity Club and the NHS.

It begins at sunrise ...

6:45 a.m.

Eric Hartley is in his classroom at Everett High School early today. The end of the first marking period is near, and he needs to post grades and prepare for upcoming parent conferences prior to first period Senior Math class at 7:40. Today’s lesson: “Linear Combinations.”

The previous night was spent the same way this evening will be; on a football field armed with a whistle and flag.

“We were at Dansville,” Hartley says. “Rained a bit, but nothing too bad. It was decent football, and only one game, as opposed to the two we might get on other Thursdays.”

Another game looms on the horizon a half-day away. But first, there is a day’s worth of classes to teach, as the bell sounds for first hour.

7:50 a.m.

Leroy Hackley settles into his office at Jenison, coordinating calendars with Assistant AD Todd Graham and Secretary Moni Marlink. Today’s activities include a subvarsity football doubleheader and a swimming & diving meet, while MHSAA Division 4 Tennis Finals and a water polo tournament during the weekend add additional responsibilities to the routine calendar of events.

“I realize how good we have it here,” Hackley says. “I’ve got a full-time assistant and full-time secretary, and we all complement one another so well. Todd’s a taskmaster who loves to handle the paperwork, Moni is on top of tasks like rosters, game programs, certificates and eligibility and I can focus on schedules, contracts and parents.”

8:00 a.m.

Senior Math students at Everett are checking their first grades of the fall and working on graphs while Hartley makes the rounds assisting students and answering questions.

He began first hour the same way he would start each of his classes that day, encouraging students’ parents to attend teacher conferences the following week. Extra credit would be awarded to students whose parents made it to the conference. Aware that athletic events and an area-wide high school “Battle of the Bands” could create conflicts on conference night, Hartley requests phone calls or emails from parents who plan to attend such approved school-related endeavors in lieu of the conferences.

“Today, we try to do everything possible to keep parents involved and informed on student progress,” Hartley explained. “And, when there are other school activities going on and they are supporting their kids at those events, we should recognize that too.”

Of course, not every scenario can be anticipated in today’s ever-shrinking world. At the end of the period, Hartley is approached by a foreign exchange student who indicates his sponsor family is away in Cuba. And so, before 8:30 a.m., Hartley’s officiating skills click in and he makes a quick ruling, citing the same “rule book” reference that will afford the others credit via an email or phone call.

8:15 a.m.

It’s between classes at Jenison High School, and Hackley rushes from his desk to a prime spot in the hallway between the administrative and athletic offices where the pedestrian flow is swift and plentiful. Once there, he delivers his first high-five of the day, but it’ll be far from his last. Hackley might lead the state in high-fives, and is unabashedly the Wildcats’ biggest cheerleader.

“I like to come out between classes and ‘press the flesh,’” Hackley says, beaming.

And the assault begins.

“How’s that knee going?”

“Gonna cheer on our guys tonight, right?”

“Nice job last night!”

The last stragglers make it to the next class, and it’s time to take a visitor on a tour of the facility which, by the way, would be the envy of many a small college.

The tour begins with a stop at the girls swimming & diving donut table, a regular fixture in the corner of a hallway on this day of the week, with proceeds going to the swim team. After a brief stop in the gym and accidental participation in a “speedball” game, it’s off to the football and soccer fields, then a check on the tennis courts, 16 of them with bleacher seating. It’s little wonder the MHSAA?Finals have made the school a regular destination.

9:40 a.m.

Second period trigonometry – complete with some elements of the Pythagorean Theorem mixed in with today’s free-space trig session – comes and goes, and for the first time Hartley begins to think about the night’s football assignment at Fowlerville.

As the crew’s referee, he typically sends emails to his crew and the host athletic director each Sunday confirming arrival time, gametime, travel plans and facility availability.

As gameday closes in, he admits there is a different feel to the day in the classroom, although many of the elements are applicable inside and outside the walls.

“Classroom management, discipline and dealing with kids correlates directly to game management, enforcement of penalties and dealing with coaches,” Hartley said. “It’s managing students and working with administrators both in class and on the field. Like the games, some classes involve mostly teaching and run smoothly. Others require more management, control, discipline and then, ‘Oh yeah, I have to fit in some teaching too.’”

As the wind whips outside, and rain pelts the classroom windows, he wonders if it might not be a better day for basketball.

With the game hours off, but the next class just minutes away, he tunes his laptop to 70s music on Sirius/XM radio and gets the next lesson ready on his Smartboard. A neighboring teacher comes in to borrow pencils; there might not be a need for chalk anymore, but pencils have not been replaced.

9:50 a.m.

Having answered and cleared his email to start the day, Hackley returns from his rounds to find 24 more emails. Most are routinely answered. One will take some coordination with the choir teacher.

“We have a conflict with a choir performance and the last football game of the year,” he says. “We have some cheerleaders who also are in choir, so we need to arrange to have them cheer half the game and get them back for the performance.”

That’s not the only juggling act of the day. Superintendent Tom TenBrink calls shortly before 10 a.m. to discuss impending O-K Conference divisional realignments, not an easy process when 51 schools are involved.

“We are in the Red with Hudsonville, Rockford and East Kentwood and have asked to be relieved from the Red,” Hackley said. “We are one of the smallest schools by far. Travel might be further in other divisions, but we need to be where the enrollments and competition are more equitable.”

It’s not as simple as a vote of ADs. The ADs have advisory votes, the principals have votes to approve plans, then it goes to school boards.

Once again, Hackley is appreciative of his footing at Jenison.

“We – superintendent, principal and I – talk all the time and we are all in the loop. The communication is a real plus for me being an advocate for our kids, because I know it’s not like that at a lot of places,” Hackley said.

10:40 a.m.

Hartley is accustomed to throwing a lanyard around his neck during his avocation of officiating, but he puts one on early today for fourth-hour trig. One of the students in this class has a hearing disability and sometimes is accompanied with a signer for assistance. Today, the student brings a small amplifier for Hartley to wear during the class.

“That’s the first time I’ve been given that to wear,” he said. “Sometimes the student doesn’t have the assistant there either. It depends on the complexity of the classes that day.”

Across the state at Jenison, Marlink has printed programs for the evening’s football and swimming events, and is on her way to Subway to order food for the weekend’s tennis and water polo tournaments. En route, she’ll stop at the football field to drop off a supply of pop before returning to the office.

Graham is preparing money boxes for the ticket gates, when Hackley prepares an email to alert students and staff of special parking procedures and bus routes affected by the MHSAA?Tennis Finals.

Junior high cross country coach and high school teacher Karina White stops by and says, “Thanks for the help yesterday.”

Hackley explains that the high school had no activities so he went to help administer the junior high meet. One gets the feeling this is routine.

11:25 a.m.

Hackley takes a brief moment to look up the Culpepper (Virginia) Football Association online, where he tracks the early football careers of his 3rd, 4th and 5th-grade nephews. The phone cuts his research short, however, as a caller asks where to find MHSAA?Tennis Finals seedings and results for the coming weekend. This is an easy one for Hackley, as he’s the one who will be sending files to the MHSAA during the event.

Noon

Lunchtime is more like crunchtime back in Lansing for Hartley, who has the whole process timed to the minute, as if the play clock were running down on a quarterback.

“Got about 27 minutes by the time all is said and done,” he says on a brisk trip to McDonald's. The meal is ordered to-go, and eaten back in the classroom just before the bell for his final class of the day.

Hackley, meanwhile, has a bit more time and heads to Grand Rapids-area Italian favorite Vitale’s for some dine-in pizza, where an altogether different situation unfolds on the big-screen TVs.

An attempted bank robbery in small-town Ravenna dominates the local channels and the conversation. The ensuing chase and chain of events has closed down a portion of I-96 near Walker, prompting a phone call to Hackley’s son, Mitch. Mitch is a freshman at Muskegon Community College, who comes home to assist on the chain crew at home football games, and I-96 is the quickest route. In this case, Mitch will be traveling East, the opposite direction of the blockade, but Hackley calls nonetheless to advise his son.

12:55 p.m.

While Hackley has recently completed another round of high fives in the Jenison hallway, challenging a football player to test the limits of his scoreboard, Hartley has his own challenge in front of him. He needs to bring out his game management officiating skills a bit early to take control of his Algebra 1 class, made up mostly of freshmen who can smell the weekend.

“One teacher talking, 35 students learning right now. People talking now will be asking questions later, which I will not answer,” he warns, and the chatter subsides through the end of the period.

Perhaps it was a bit of foreshadowing, as it won’t be the last time he’ll need to address behavior on this day.

1:30 p.m.

As if on cue from Hackley’s earlier comments regarding communication up and down the administrative chain of command, Superintendent TenBrink drops by the office to deliver updated news on the O-K realignment.

Moments later, Mitch arrives from Muskegon and gets some last-minute instruction from Dad prior to his work at the stadium.

Hartley’s teaching duties have been completed for another week, but he’ll stay in the classroom a bit longer to tend to his first marking period grades, just as he had done at the beginning of the day.

2:00 p.m.

Hackley goes through a checklist, surfs for a weather forecast, gets a printed itinerary from Marlink for the weekend, then grabs the money boxes and programs and heads toward the field.

On the way, the door to the music room is open and a female student vocalist is performing a stirring solo number. Hackley pauses to watch through its conclusion and applauds. The students and instructor turn to acknowledge Jenison’s No. 1 fan.

After unlocking the bathrooms and getting the money to the concessions booth, Hackley sets up the officials room, chats with the athletic trainer, and then heads up to the press box where unwanted guests had been seeking refuge from the coming colder weather.

Flies – maybe a hundred – lay dead on the countertops, while a few buzz slowly against the windows certain to meet the same fate. Unfazed, Hackley simply grabs a broom and says, “I’m glad I came out a little early,” then sweeps them up and leaves the windows open a bit just in case the few living pests want to try their luck back outside.

2:45 p.m.

Carly Joseph, a junior at Pontiac Notre Dame Prep, exhales at the sound of the final school bell and utters, “I’m exhausted.” It’s been a long academic week with a course load that includes three AP and two honors classes.

But, Joseph also runs cross country, and this week has already featured a meet on Tuesday and more than 40 miles run during practice. Another practice is on the horizon, one last tune-up for a huge invitational scheduled for Carly and her teammates the next day.

In Lansing, it’s time for Hartley to guide his own “students,” as he heads home for a couple hours before meeting his crew for the trip to Fowlerville. At home, he will make sure sons Trevor and Austin get their homework done.

“I push them to get it done on Fridays after school, because on Saturdays and Sundays they officiate youth football with me, so their time is limited,” Hartley says.

4:00 p.m.

Joseph’s Notre Dame Prep team is headed to Holly High School’s cross country invitational Saturday morning, but first, it gets in one last practice. An easy four-mile run followed by eight progressive strides down the football field marks the shortest practice of the year.

It’s a good time for the short workout, because Joseph and her teammates have dinner plans in Clarkston. The team heads to Carly’s house for a pasta dinner prepared by her parents.

5:00 p.m.

Vicky Groat sends her Battle Creek St. Philip volleyball team home following a two-hour practice, its final preparation for Saturday’s 34th Battle Creek All-City Tournament. Groat has set her players free for the night. They have a curfew of 10 p.m., and although she calls on occasion to keep them honest, she won’t this time. There are other preparations for the next day’s tournament that will keep her busy into the evening, as we’ll see later.

At a parking lot in Okemos, Hartley’s crew gathers for a short ride to Fowlerville, which has a conference battle with Haslett. At this point, there is more talk of the weather than the game, as 30 mile-per-hour winds, rain, and temperatures in the 30s promise to make things uncomfortable.

6:15 p.m.

Eighty shoes are piled high just inside the front door of the Joseph house, as 40 Notre Dame Prep runners and coaches gather for the meal. Kids have seized every room in the house, and as one would expect, there’s rarely a quiet moment. Mrs. Joseph serves platefuls of penne, lasagna, salad, rolls and a brownie (or two). Clearly, it is a scene that would dispel the myth that distance runners don’t eat.

In Fowlerville, Hartley and his crew walk from the locker room to the playing field which, remarkably, is in great shape for the amount of rain it’s taken on. The crowd is sparse for Senior Night, as the officials meet with each coach and then conduct the coin toss.

8:00 p.m.

In a modified game of Twister, dozens of people search Shoe Mountain as two-by-two the shoes clear the Joseph house. Suddenly, all is quiet. The Joseph family does some quick cleanup – including vacuuming brownie crumbs out of the carpet – and is able to relax.

At nearly the same time one county over, the mood is anything but serene. It’s time for serious game management as temperatures on the field are beginning to heat up the atmosphere. The Fowlerville-Haslett football game is getting chippy after each play, and Hartley quells the extracurriculars by calling both coaches to the field to discuss matters in the middle of the second quarter. The impromptu summit works, as kids get back to football as it’s meant to be played.

9:00 p.m.

Lights are out for Joseph, with tomorrow’s race in Holly one of the biggest of the year.

The lights are on, however, in Groat’s basement. She wants her team to look good for the All-City Tournament, but she’s not reviewing opponents’ tendencies or diagramming offensive sets. At the moment, she is screen-printing shirts in her basement. St. Philip will debut new red jerseys Saturday. Oh, by the way, Groat also is in her fourth year as the school’s athletic director.

9:49 p.m.

Hartley and Co. head out of Fowlerville High School – roughly 15 hours after his day began – through an empty hallway to an empty parking lot. Haslett pulled away in the second half for a 40-21 win, and another week was in the books for this crew.

The next two days are ones which Hartley relishes, the opportunity to pass along his passion for officiating while mentoring his sons.

Hackley also is calling it a day in Jenison, but the night’s sleep will be fast with the MHSAA Tennis Finals and the water polo invite the next day. The “to-do” list Marlink prepared for him during the day has Saturday’s first item slated for 7 a.m.

11:30 p.m.

Right about now, Groat is probably thankful she’s not coaching a football team, as she completes the last of her team’s shirts. At this point, Saturday is only 30 minutes away.

5:31 a.m.

The alarm goes off in Joseph’s room – it’s race day. After a breakfast of maple brown sugar granola cereal, whole wheat toast and orange juice, she heads to the school for a 7 a.m. bus departure. “I’m our seventh runner, but one of our team strengths is our depth. I have to keep pushing those ahead of me to help the team succeed,” Joseph explains.

7:00 a.m.

While Joseph and her teammates board the bus bound for Holly, tennis courts at Jenison will begin to come to life shortly. Before they do, Hackley (left) is off to Ida’s Bakery to pick up a dozen cinnamon rolls and danishes, followed by a stop at Subway to grab 15 box lunches for tournament officials at the MHSAA?Tennis Finals.

Since it’s Saturday, Hackley and Graham arrive early to pick up trash, replace bags, and open the restrooms. “Saves on maintenance overtime,” he says.

7:45 a.m.

The Notre Dame Prep cross country team arrives at Springfield Oaks County Park, and a long line of busses greet them at the gate. After a short wait, the team de-boards, finds the perfect camp spot and sets up three canopy tents for all the varsity and JV runners. Once their spot is staked out, the varsity girls head out for a warm-up run.

8:05 a.m.

Groat arrives at Pennfield High School, followed over the next 10 minutes by her players. Some of the team’s tournaments mean waking up at 5:45 a.m. for a 7 a.m. departure. This invitational, close to home, has afforded everyone another hour of sleep. Groat is plenty familiar with the All-City. At the end of this day she’ll leave with her sixth championship as St. Philip’s coach. And she was a senior on the 1985 team that won the school’s first All-City title under Groat’s mother, Sheila Guerra.

8:55 a.m.

Joseph and her teammates report to the starting chute, perform some last-minute stride-outs, take off layers of clothing, and grab attention with their unique team cheer. “Everyone always stares at us as we do the cheer, but it helps loosen us up right before the race begins,” Joseph said.

They’re lined up three-deep in the starting box, and at 9 a.m. sharp, the gun sounds and 113 runners take off.

About 100 miles southwest, Groat and the Tigers are ready for the first match of the day vs. Harper Creek. Following warm-ups, the team gathers in a circle for a pre-match prayer – the same one they’ve said before matches for five years. Some girls were in charge of bringing hair ribbon for the team, others had other tasks. Senior Megan Lassen was to find an inspirational quote, and before the huddle breaks she reads it off her hand to her teammates. The match starts at 9:03.

To the northwest, the courts at Jenison again become a hub of activity, as teams vie for the MHSAA?Division 4 title.

9:18 a.m.

In Holly, Rachele Schulist of Zeeland West (the reigning MHSAA Division 2 Cross Country champion) crosses the finish line first, with Notre Dame Prep’s Sara Barron in second. Joseph finishes in 22:41 (sixth on her team) as the Irish run their best team race of the year.

9:37 a.m.

St. Philip finishes the first match of pool play with a 25-12, 25-17 win over Harper Creek. It’s a good sign for a few reasons – Harper Creek is a solid program coming off a District title in 2010, and Groat has to run a home football game kicking off in nine hours. It’s “Parents Night” for the football players, and she’s banking on volleyball being done by 4 p.m. in case she needs to make a pick-up at the florist on the way to setting up.

10:26 a.m.

After beating Pennfield, 25-18, to open the second round of pool play, the Tigers fall in the second game, 26-24. This is a rarity – despite playing a number of much larger schools throughout the fall, St. Philip began the tourney with a 37-3-1 record. Groat doesn’t say much to her players afterward – by design. She expects them to prepare themselves without her giving an additional push. Sometimes it’s hard to not jump in, but she can tell after this split it isn’t necessary.

“By the looks on their faces, they knew they weren’t ready to go,” Groat said. “In Game 2 we didn’t play very well, and Pennfield had the intensity there. Our girls knew they didn’t come ready to play. I didn’t have to say it.”

11:30 a.m.

Teams congregate in the pavilion area for the awards ceremony at Springfield Oaks. Pontiac NDP hasn’t won a trophy in a few years, but fortunes have changed today and  the girls are excited to accept the fourth-place team trophy.

the girls are excited to accept the fourth-place team trophy.

“I can’t wait to show (NDP Athletic Director) Ms. Wroubel. We’ll find a place for it in the trophy case,” Joseph said.

With the great finish today, it’s hard not to talk about making the MHSAA Finals in November.

11:48 a.m.

The Tigers get a bye and then lunch break back-to-back. So after nearly an hour-and-a-half they begin warming up for their third pool play match, against Battle Creek Central. During the bye, St. Philip players kept score or served as line judges for other matches, while Groat talked with parents and watched a little bit of Lakeview – the Tigers’ eventual championship match opponent.

12:15 p.m.

Joseph returns to Clarkston for some homework and rest, but her sporting weekend is far from over. She’ll head to Roseville the next day for three games with her travel softball team, including two where she’ll be on the mound. And then she’ll cap off the weekend with a 12-mile run, get ready for school on Monday and repeat the cycle.

1:36 p.m.

St. Philip has swept Central and Lakeview to finish pool play, and changes into the new red jerseys Groat finished the night before. Next up is a semifinal match against Harper Creek – which the Tigers win in two games. They’ve bounced back while maintaining the cool demeanor of their coach.

“We always just take deep breaths, because if we get riled by anything, we get nervous,” St. Philip junior Amanda McKinzie said. “She’s usually pretty calm about it, which is always helpful. She probably has to hold back pretty hard, because if we start losing, it’s kind stressful.”

2:27 p.m.

The final begins. By 3:07 p.m., the Tigers have won 25-22 and 25-5 to clinch their fourth-straight All-City title. The Pennfield split might have been a blessing in disguise.

“Sometimes a loss is good for a program. It kind of woke us up,” Groat said. “It can’t happen Oct. 31 (when Districts begin).”

3:24 p.m.

Groat leaves Pennfield for St. Philip to prepare the public address announcements for the football game and pick up flowers, the money box, water and checks for the officials who will work that night. Earlier in the day she’d secured someone to take tickets – her niece, also a former volleyball player – and by 5:45 she’s on her way to Battle Creek Central’s C.W. Post Stadium, less than half a mile from St. Philip and the home field for the Tigers.

3:37 p.m.

The MHSAA receives Hackley’s final email of the weekend after he’s entered data for the Division 4 Tennis Finals. Hackley comments on the great finish that came down to the last match, as Ann Arbor Greenhills claimed the title by one point over runners-up Lansing Catholic and Kalamazoo Christian. The bus routes can go back to normal at Jenison once again on Monday.

9:20 p.m.

Groat’s athletic director duties are done for the night. She picks up a pizza and gets home to Marshall by 10 p.m. It was a busy day, but despite being tired she needs time to wind down before going to sleep at midnight.

Sunday

The day of rest finally is here. For Hackley and Hartley, it means a 9 a.m. meeting at the MHSAA office in East Lansing, where the two attend a mandatory Michigan Community College Athletic Association Women's Basketball Officiating staff meeting. Both work women’s basketball in their “spare” time. Hartley will then be off to another football field to work youth ball again with his sons.

Joseph, meanwhile, is off to Roseville for the softball tripleheader. One thing is for sure: with her daily running regimen, her legs are more than up to that task.

For Groat, it’s a little more low-key, as friends come to her house to watch the Detroit Lions game. But volleyball still owns a time slot in the day – that night, Groat will update her team’s season stats.

Like virtually every other official, administrator, coach and student-athlete around the state, none even stop to think about the frenetic pace. In Groat’s case, there is a little extra motivation. The memory of her mom – who died in 2006 – is never far off.

“I put a little more pressure on myself. I don’t want to let the legacy down,” Groat said. “My driving force is to not let her down and I don’t want to let the kids down. It’s a great opportunity for them to play and make lasting memories.”

In turn, the memories are passed on to countless supporters in communities throughout the state.

Websites and scoreboards display the winners, losers and some statistics. The power is supplied by the people in school sports – whether behind the scenes or on center stage – who simply seem to be wired a little differently.

For that, we all are thankful. One might even agree it’s worth the price of admission.

–Compiled by MHSAA?staff members Rob Kaminski, Andy Frushour and Geoff Kimmerly