The More Things Change ...

December 20, 2013

By Rob Kaminski

MHSAA benchmarks editor

As we begin another calendar year, let's take a brief look at how the mission of school sports has (or hasn’t) changed since 1955, when former MHSAA Executive Director Charles E. Forsythe presented this practicum to the University of Michigan.

The following is an excerpt:

Presented by Charles E. Forsythe

Practicum in Physical Education

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Tuesday, June 21, 1955

WHY DO WE HAVE INTERSCHOLASTIC ATHLETICS IN OUR SCHOOLS?

To meet the urge for competition which is a basic American tradition – let’s keep it.

To meet the urge for competition which is a basic American tradition – let’s keep it.- To provide a “whole school” interest and activity, bring in students other than athletes, enlist many student organizations.

- To teach students habits of health, sanitation, and safety.

- Athletics teach new skills and opportunities to improve those we have; this is basic educationally.

- To provide opportunities for lasting friendships both with teammates and opponents.

- To provide opportunity to exemplify and observe good sportsmanship which is good citizenship.

- Athletics give students a chance to enjoy one of America’s greatest heritages, the right to play and compete.

- One of the best ways to teach that a penalty follows the violation of a rule is through athletics.

- There must be an early understanding by students that participation in athletics is a privilege which carries responsibilities with it. Awarding school letter to a student is the second-highest recognition his school can give him – his diploma at graduation is the highest.

- To consider interscholastic athletic squad as “advanced” classes for the teaching of special skills – similar to bands, orchestras, school play casts, members of debating teams, etc. There is no reason why a reasonable amount of attention should not be given to such groups – as well as to those in the middle and lower quartiles in our schools. Both leaders and followers must be taught.

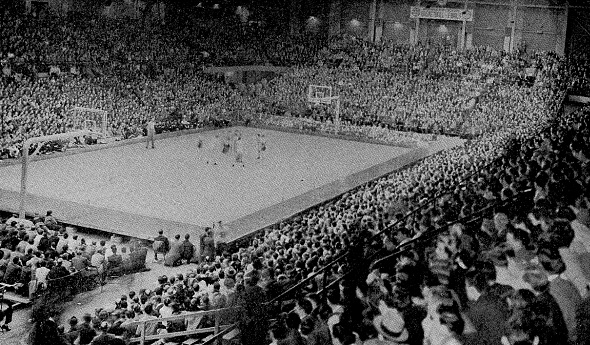

PHOTOS: (Top) Fans filled the arena for this MHSAA boys basketball tournament game. (Middle) Charles Forsythe served as the first executive director of the MHSAA.

High School a Time for Plays of All Kinds

April 2, 2015

By Jack Roberts

MHSAA executive director

At end of season or school year banquets attended by student-athletes and their parents, I often tell this short story about my mother that never fails to get a good laugh, especially from mothers:

“At the end of my junior year of high school I attended the graduation ceremony for the senior class on a hot and humid early June evening in our stuffy high school gymnasium. The bleachers on each side were filled to capacity, as were several hundred folding chairs placed on the gymnasium floor.

“The public address system, which was wonderful for announcing at basketball games or wrestling meets, was awful for graduation speeches. Person after person spoke, and the huge audience wondered what they had to say.

“I was present because I was the junior class president; and as part of the ceremony, the senior class president handed me a small shovel. It had something to do with accepting responsibility or carrying on tradition.

“In any event, the senior class president spoke briefly; and then it was my turn. I stepped to the podium, pushed the microphone to the side, and spoke in a voice that was heard and understood in every corner of the gymnasium.

“Whereupon my mother, sitting in one of the folding chairs, positioned right in front of my basketball coach – who had benched me for staying out too late on the night before a game, because I had to attend a required school play rehearsal – my mother turned around, pointed her finger at the coach and said, ‘See there? That’s what he learned at play practice!’

“And she was heard in every corner of the gymnasium too.

“But my mother knew – she just knew – that for me, play practice was as important as basketball practice. And she was absolutely correct.”

This old but true story about in-season demands of school sports actually raises two of the key issues of the debate about out-of-season coaching rules.

One is that we are not talking only about sports. School policies should not only protect and promote opportunities for students to participate in more than one sport; they should also allow for opportunities for students to participate in the non-athletic activities that comprehensive, full-service schools provide.

This is because surveys consistently link student achievement in school as well as success in later life with participation in both the athletic and non-athletic activities of schools. Proper policies permit students time to study, time to practice and play sports and time to be engaged in other school activities that provide opportunities to learn and grow as human beings.

A second issue the story presents is that parents have opinions about what is best for their children. In fact, they feel even more entitled to express those opinions today than my mother did almost 50 years ago. In fact, today, parents believe they are uniquely entitled to make the decisions that affect their children. And often they take the attitude that everyone else should butt out of their business!

The MHSAA knows from direct experience that while school administrators want tighter controls on what coaches and students do out of season, and that most student-athletes and coaches will at least tolerate the imposed limits, parents will be highly and emotionally critical of rules that interfere with how they raise their children.

No matter the cost in time or money to join elite teams, take private lessons, travel to far-away practices and further-away tournaments, no matter how unlikely any of this provides the college athletic scholarship return on investment that parents foolishly pursue, those parents believe they have every right to raise their own children their own way and that it’s not the MHSAA’s business to interfere.

It is for this very reason that MHSAA rules have little to say about what students can and can’t do out of season. Instead, the rules advise member schools and their employees what schools themselves have agreed should be the limits. The rules do this to promote competitive balance. They do this in order to avoid never-ending escalating expense of time and money to keep up on the competitive playing field, court, pool, etc.

Every example we have of organized competitive sports is that, in the absence of limits, some people push the boundaries as far as they can for their advantage, which forces other people to go beyond what they believe is right in order to keep up.

If, during the discussions on out-of-season rules, someone suggests that certain policies be eliminated, thinking people will pause to ask what life would be like without those rules.

Our outcome cannot be mere elimination of regulation, which invites chaos; the objective must be shaping a different future.

A good start would be simpler, more understandable and enforceable rules. A bad ending would be if it forces more student-athletes and school coaches to focus on a single sport year-round.