Using Heads in the Heat of Competition

December 20, 2013

By Rob Kaminski

MHSAA benchmarks editor

With so much recent attention to the risks and recognition of concussions in collision sports, athletic leaders have put their heads together to address far more common – but often overlooked – threats to the health of our student-athletes: heat and sudden cardiac arrest.

The No. 1 killer of young athletes is sudden cardiac arrest, while heat stroke victims can surpass that during the year’s hottest months. While the moment of impact leading to a concussion is totally unpredictable, athletic trainers, coaches and administrators have the ability to diminish the occurrences of cardiac arrest and heatstroke. Typically, there is a pre-existing condition, or family history suggesting probabilities for sudden cardiac arrest, which can be treated when detected. And, the perils associated with hot weather – heat stroke, prostration – are almost always completely preventable.

The MHSAA has addressed both issues recently. With assistance from numerous medical governing bodies, the annual pre-participation physical form was revamped and expanded prior to the 2011-12 school year to include comprehensive information regarding participants’ medical history.

In May, the Representative Council adopted a Model Policy for Managing Heat & Humidity (see below), a plan many schools have since adopted at the local level. The plan directs schools to monitor the heat index at an activity site once the air temperature reaches 80 degrees and provides recommendations when the heat index reaches certain levels, including ceasing activities when it rises above 104 degrees.

The topic of heat-related illnesses receives a lot of attention at the start of fall when deaths at the professional, collegiate and interscholastic levels of sport occur, especially since they are preventable in most cases with the proper precautions. In football, data from the National Federation of State High School Associations shows 41 high school players died from heat stroke between 1995 and 2012.

“We know now more than we ever have about when the risk is high and who is most at risk, and we’re now able to communicate that information better than ever before to administrators, coaches, athletes and parents," said Jack Roberts, executive director of the MHSAA. “Heat stroke is almost always preventable, and we encourage everyone to avail themselves of the information on our website.

“Schools need to be vigilant about providing water during practices, making sure that students are partaking of water and educating their teams about the need for good hydration practices.”

All of which is not to say concussions aren’t a serious matter; they are. In fact, leaders in sport safety can take advantage of the concussion spotlight to illuminate these additional health threats.

A recent New York Times story (May 2013) by Bill Pennington featured a February 2013 gathering in Washington organized by the National Athletic Trainers Association. In the article, Dr. Douglas J. Casa, professor of kinesiology at the University of Connecticut and Chief Operating Officer of the Korey Stringer Institute (founded in the late NFL offensive lineman’s name to promote prevention of sudden death in sport), suggests just that.

“All the talk about head injuries can be a gateway for telling people about the other things they need to know about, like cardiac events and heat illness,” said Casa in the article. “It doesn’t really matter how we get through to people as long as we continue to make sports safer.”

Education and prevention methods need to find a permanent place in school programs if those programs are to thrive and avoid becoming targets at which special interest groups can aim budgetary arrows.

Dr. Jonathan Drezner, the president of the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, said in the New York Times piece that sudden cardiac arrest is “so incredibly tragic and stunning that people aren’t comfortable putting it into the everyday conversation. I do wish, to some extent, it was something people talked more about because we are getting to a place where we could prevent many of these deaths.”

When it comes to heat-related deaths or illnesses, the prevention efforts can be even more successful by educating the masses. And, these efforts can be done at minimal cost to schools.

“That’s the thing about curtailing exertional heat illness: it’s 100 percent preventable, and unlike other health threats to athletes, the solutions can be very low-tech and inexpensive,” said Dr. Michael F. Bergeron, the director of the National Institute for Athletic Health & Performance at the University of South Dakota’s Sanford Medical Center, in the New York Times story.

To assist with cost and data maintenance, the MHSAA has teamed with Sports Health to provide schools with psychrometers (heat measurement instruments) at a discounted rate, and has built online tools to track heat and humidity conditions.

Managing heat and humidity policy

- Thirty minutes prior to the start of an activity, and again 60 minutes after the start of that activity, take temperature and humidity readings at the site of the activity. Using a digital sling psychrometer is recommended. Record the readings in writing and maintain the information in files of school administration. Each school is to designate whose duties these are: generally the athletic director, head coach or certified athletic trainer.

- Factor the temperature and humidity into a Heat Index Calculator and Chart to determine the Heat Index. If a digital sling psychrometer is being used, the calculation is automatic.

If the Heat Index is below 95 degrees:

All Sports

- Provide ample amounts of water. This means that water should always be available and athletes should be able to take in as much water as they desire.

- Optional water breaks every 30 minutes for 10 minutes in duration.

- Ice-down towels for cooling.

- Watch/monitor athletes carefully for necessary action.

If the Heat Index is 95 degrees to 99 degrees:

All Sports

- Provide ample amounts of water. This means that water should always be available and athletes should be able to take in as much water as they desire.

- Optional water breaks every 30 minutes for 10 minutes in duration.

- Ice-down towels for cooling.

- Watch/monitor athletes carefully for necessary action.

Contact sports and activities with additional equipment:

- Helmets and other possible equipment removed while not involved in contact.

- Reduce time of outside activity. Consider postponing practice to later in the day.

- Recheck temperature and humidity every 30 minutes to monitor for increased Heat Index.

If the Heat Index is above 99 degrees to 104 degrees:

All Sports

- Provide ample amounts of water. This means that water should always be available and athletes should be able to take in as much water as they desire.

- Mandatory water breaks every 30 minutes for 10 minutes in duration.

- Ice-down towels for cooling.

- Watch/monitor athletes carefully for necessary action.

- Alter uniform by removing items if possible.

- Allow for changes to dry T-shirts and shorts.

- Reduce time of outside activity as well as indoor activity if air conditioning is unavailable.

- Postpone practice to later in the day.

Contact sports and activities with additional equipment

- Helmets and other possible equipment removed if not involved in contact or necessary for safety.

- If necessary for safety, suspend activity.

Recheck temperature and humidity every 30 minutes to monitor for increased Heat Index.

If the Heat Index is above 104 degrees:

All sports

- Stop all outside activity in practice and/or play, and stop all inside activity if air conditioning is unavailable.

Note: When the temperature is below 80 degrees there is no combination of heat and humidity that will result in need to curtail activity.

PHOTO: The Shepherd volleyball team includes hydration during a timeout in a match this fall.

Family Coaching Tree Grows to 3 Generations

By

Tom Markowski

Special for Second Half

September 13, 2018

Like father like son, like grandson.

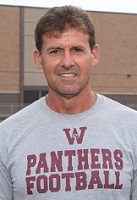

The Grignon football family continued its progression in the coaching ranks this season when Alex Grignon got his shot at being a head coach. Grignon was hired in June as head coach at Walled Lake Western to replace Mike Zdebski, who resigned to take a coaching position in Arizona.

The Grignon football family continued its progression in the coaching ranks this season when Alex Grignon got his shot at being a head coach. Grignon was hired in June as head coach at Walled Lake Western to replace Mike Zdebski, who resigned to take a coaching position in Arizona.

Alex Grignon, 31, represents the third generation from a family of past and present high school head football coaches. And one can’t talk football in Wayne County communities like Dearborn and Lincoln Park without mentioning the Grignon family.

Ted Grignon was the athletic director and head football coach at Lincoln Park in the 1980s. His two sons, Ted and Jamie, played football at Dearborn Edsel Ford and then in college – Ted, a quarterback at Western Michigan University and Jamie, a safety at Grand Valley State. Jamie Grignon is in his third stint as Lincoln Park’s head coach. He was hired in 1994 and stepped aside after the 1999 season, but never left the sport as he went to Dearborn High as an assistant under Dave Mifsud in 2000. Grignon went back to Lincoln Park in 2013 as the head coach and, after taking another brief hiatus, came back last season and remains in that position.

His two sons, Andrew and Alex, played for Mifsud at Dearborn; and in 2004, Alex’s senior season, Dearborn reached a Division 2 Semifinal before losing to Orchard Lake St. Mary’s, 6-0. It marked the first time the program advanced that far in the MHSAA Playoffs.

Andrew switched sports and played lacrosse in college (at Grand Valley), but his younger brother stuck with football. After playing four years at Northern Michigan, Alex was a graduate assistant there working with the offense before joining his father’s staff at Lincoln Park.

Andrew switched sports and played lacrosse in college (at Grand Valley), but his younger brother stuck with football. After playing four years at Northern Michigan, Alex was a graduate assistant there working with the offense before joining his father’s staff at Lincoln Park.

The Railsplitters have had their struggles of late, starting this season 0-3 and last making the playoffs in 2015. But in 2013, with Jamie as the head coach and Alex as the defensive coordinator, Lincoln Park ended a 66-game losing streak by defeating Taylor Kennedy, 34-20.

After five seasons at Lincoln Park, Alex went to South Lyon last season as the offensive coordinator, and this season he made the big jump. Walled Lake Western is one of the top programs in the Detroit area and a member of the Lakes Valley Conference, and Grignon has the Warriors off to a 2-1 start.

“He was proud that he was the third generation (of head coaches),” Jamie Grignon said. “When he coached with me, it was a growing process for him. There isn’t anyone who works harder than Alex. Whether it’s watching film, working with the kids after practice or what. He’s full-go.”

Like father like son. Jamie is not one to toot his own horn, but when he was the defensive coordinator at Dearborn people in the Downriver area, and in other football strongholds in the county, knew Mifsud had one of the best coaches calling his defense.

Mifsud is in his sixth season as the head coach at Parma Western after serving 16 in the same position at Dearborn. He was an assistant coach at Dearborn for four seasons before being named head coach in 1997.

Remember those dates. Before Mifsud was able to hire Grignon, the two met as adversaries on the field. Lincoln Park defeated Dearborn, 14-0, during Dearborn’s homecoming, no less, in 1999. That was Grignon’s last season during his first stint at Lincoln Park.

Remember those dates. Before Mifsud was able to hire Grignon, the two met as adversaries on the field. Lincoln Park defeated Dearborn, 14-0, during Dearborn’s homecoming, no less, in 1999. That was Grignon’s last season during his first stint at Lincoln Park.

Mifsud didn’t have to twist Grignon’s arm to join his staff at Dearborn. Grignon’s oldest son, Andrew, was set to play for Mifsud in 2000. Alex is two years younger, so Mifsud was secure knowing the Grignons had his back.

“I was in my fourth year when Andrew came through, I hired Jamie and Keith Christnagel, who’s the coach at Woodhaven now,” Mifsud said. “We grew up together, the three of us, as coaches. We racked our brains learning the ropes. I always coached the offense. Keith had the offensive and defensive lines and Jamie the defense. The working relationship with Jamie was excellent. We split up the special teams, though he probably did more there.

“People know of Jamie, and he worked his tail off. On Sundays I’d stop by, you know, just to drop some film off or just to touch base, and his entire dining room would be spread all around with notes on breaking down the other team’s offense and such. Jamie’s a high-energy guy. He’s always thinking.

“Looking at Alex, yeah, I think they are similar. They can’t sit still. They’re always looking for something better. What a great hire (for Walled Lake Western). Alex is so great with the kids. He’s young (31). He’s got great football intelligence. Jamie was like that. He would tweak things in practice. He’d never be satisfied. Alex has that. He’s Jamie but at a different level.”

Mifsud and Jamie Grignon both said that what makes Alex a cut above is his leadership. As good as Alex was athletically as a player, his father said it was his leadership qualities that set him apart.

Mifsud recalled a story, a 2-3 week period, actually, during the 2004 season. The staff had yet to elect captains, and as preseason practices wore on Mifsud and his staff were taken aback by the actions of three seniors, Alex among them.

Mifsud recalled a story, a 2-3 week period, actually, during the 2004 season. The staff had yet to elect captains, and as preseason practices wore on Mifsud and his staff were taken aback by the actions of three seniors, Alex among them.

The coaches didn’t have to blow a whistle to start practice. Those three would have the players ready.

“I looked at my coaches,” Mifsud said. “And said those are our captains.”

Alex said he never thought about being a leader. It just came naturally. He grew up watching football from the sidelines, and later as a water boy, and then at home watching his father gather notes and dissect film footage.

“I was on the sidelines my entire life,” he said. “The leadership, you see it. You watch the players. You know what it takes to be a leader. I tell my players at Western, people want to be led.

“As a youth you don’t realize what level dad is coaching at, but you remember going to coffee shops exchanging film. I’d have my ninja toys with me, and the next minute I’d be holding dummies. Dad didn’t push us. He wanted us to do what we wanted to do. Heck, I was a big-time soccer player. I didn’t start playing football until middle school. For two years I did both.”

By his freshman year, Alex was all in for football. His was one of best classes the school has had for the sport, and Alex recalls that 40-50 of his classmates showed their dedication by increasing their work in the weight room.

Playing with his brother for two years and with his father for all four only made Alex more determined.

“I can’t talk football and family without getting emotional about it,” he said. “Watching your dad work 18 hours on the weekend, turning the pages of his legal pad, he was always doing something. I remember eating eggs for breakfast every day and peanut butter sandwiches for lunch to try and get as much protein in our bodies. I’d get up as a child, and he’d be on his third cup of coffee. He never stopped. He saw us wanting to be around the game, and he helped in any way he could to make us better.

“Everything I know, I’ve seen him do.”

Tom Markowski is a columnist and directs website coverage for the State Champs! Sports Network. He previously covered primarily high school sports for the The Detroit News from 1984-2014, focusing on the Detroit area and contributing to statewide coverage of football and basketball. Contact him at [email protected] with story ideas for Oakland, Macomb and Wayne counties.

Tom Markowski is a columnist and directs website coverage for the State Champs! Sports Network. He previously covered primarily high school sports for the The Detroit News from 1984-2014, focusing on the Detroit area and contributing to statewide coverage of football and basketball. Contact him at [email protected] with story ideas for Oakland, Macomb and Wayne counties.

PHOTOS: (Top) Walled Lake Western coach Alex Grignon is in his first season as head coach at Walled Lake Western. (Top middle) Alex, left, and father Jamie Grignon when Alex was assisting Jamie at Lincoln Park. (Middle) Current Parma Western and former longtime Dearborn coach Dave Mifsud. (Below) Alex and Jamie Grignon, when both were coaching Lincoln Park, and Alex with his family now as coach at Walled Lake Western. (Photos courtesy of Grignon family; Walled Lake Western photos by Teresa Presty Photography.)