After the Game: What do you say?

April 20, 2017

By Kevin Wolma

By Kevin Wolma

Hudsonville Athletic Director

“I love to watch you play.” Those are the six words a son or daughter wants to hear from his or her parents after a game.

What if your child does not play? What do you say then? Parents can’t say, “I love to watch you play” when your child does not play, nor can they say other post-competition statements like:

“Did you fight like a dog?”

“Did you have fun?”

It is hard to fight like a dog when not given the opportunity, and we all know players have more fun when they play in the game. When you google the phrase, “what to say after a game,” there are all sorts of articles written with some of them backed by research. However, when you google the phrase – “what to say when your kid does not play” – very little comes out of that search.

Why?

This is a hard and very sensitive area for most parents to come up with the right thing to say.

Before we talk about what to say in this situation, it may be more important to discuss what not to say after a game where your child does not play. Some of the comments all parents should avoid are:

“Why have you not played in the last three games? Your coach must not like you for some reason.”

“Your coach is clueless; he has no idea what he is doing.”

“You are way better than Johnny! I can’t believe he is playing more minutes than you.”

“Did you see how many mistakes Suzie made? I know if you were given the opportunity you would not make those same mistakes.”

Parents will often say these things because they are frustrated, and parents think they are comforting their child by giving them an excuse. What these comments actually do is create a divisive culture within a team. After hearing these negative comments over and over again, the athlete will eventually believe it only to see his or her attitude and effort become negatively affected over time. That athlete turns into a selfish teammate.

Now let’s put yourself in the situation where your child comes home after a game after not playing. What do you say?

The first thing you could do is talk about the game itself. Recount certain plays and make note of individuals who played well for both teams. This initial conversation takes the uncomfortable nature of the situation and sets the stage to talk about how athletes feel about not getting into the game.

There may be times when your child will not want to talk about it because he or she is upset, angry or even embarrassed. These moments of silence give the parents an opportunity to talk about the importance of being a good teammate and how an athlete can have a major impact on the team no matter what role is played. They can teach how to be the first person off the bench to congratulate or give a word of encouragement to teammates. Parents also can point out that the harder athletes work in practice, the better it is going to make the team.

In other words, we have the responsibility as parents to teach our kids the significance of living life pointed out no matter the circumstance. Living pointed out simply means to put others before yourself in everything you do. Finding ways to make the people around you the best they can be. No complaining. No excuses.

Andrew DeWitt played two years of Varsity basketball for me at Hudsonville, and he rarely had the opportunity to play. Unfortunately for him, he was a good player on two really good teams with lots of talent. He understood his role and treated practices like games – playing as hard as he could.

He would elevate the intensity of practice every day. On game nights, he was our biggest cheerleader. His impact went way beyond scoring points or getting rebounds.

Andrew’s parents were great teachers as they guided him through those tough times where it would have been easy to make an excuse or complain. Instead, they taught Andrew he could always have an influence on other people’s lives despite the role he played. What a great lesson that Andrew can carry with him for the rest of his life.

At the end of the day, one thing every parent in every situation can say that will have a positive impact is, “I love you.” Many times athletes think they are letting their parents down because of their lack of playing time. Knowing that their parents love them the same whether they play a lot or not at all has a significant impact on how the student-athlete responds to adversity, and specifically not playing in games.

I challenge all parents to use these potentially negative situations as a way to teach student-athletes valuable lessons on what it means to be a great teammate – and more importantly in teaching them to live their life pointed out. There may not be a simple six-word phrase to say when your child does not play, but there is definitely plenty to talk about.

Wolma has served as Hudsonville's athletic director since 2011 and previously coached boys varsity basketball and girls varsity golf among other teams. He also previously taught physical education and health.

Novak Mourned, Missed After 42 Years of Telling Southwest Michigan's Stories

By

Scott Hassinger

Special for MHSAA.com

November 5, 2024

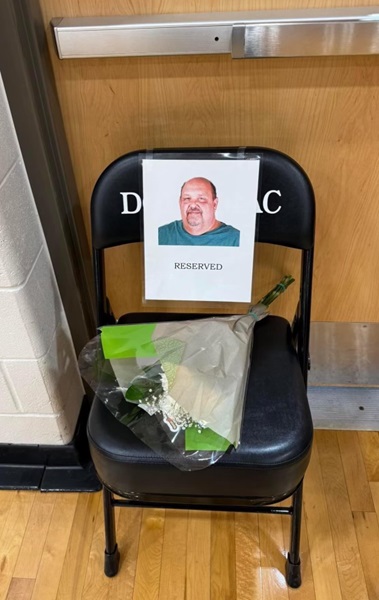

DOWAGIAC - One seat at the media table at five schools in Cass and Berrien counties will remain vacant when the 2024-25 high school basketball season tips off in a few weeks.

Scott Novak, legendary sports editor for Leader Publications for the past 42 years, won't be there to occupy his.

Scott Novak, legendary sports editor for Leader Publications for the past 42 years, won't be there to occupy his.

Novak, 63, passed away Oct. 23 following an extended illness.

Throughout his storied career, Novak earned several awards from the Michigan Press Association, The Associated Press and the Basketball Coaches Association of Michigan.

Personal recognition wasn't anything Novak sought out. In fact, the Decatur native made it his crusade to see that he got the name of every athlete he covered each sports season into the newspaper at least once.

Novak formed long-lasting relationships with coaches, athletes, parents, officials and athletic directors in the communities of Cassopolis, Edwardsburg, Buchanan, Niles Brandywine and Niles High School, along with Southwestern Michigan College.

Not only did Novak cover local high school sports, but Little League and many other youth and adult recreational sports, along with professional motocross racing at the RedBud Motocross Park in Buchanan.

Novak devoted countless hours during the week and on weekends bringing thorough coverage to Southwestern Michigan. The sports pages Novak designed for the Niles Daily Star, Dowagiac Daily News, Edwardsburg Argus and Cassopolis Vigilant contained more than just stories and photos. The weekly sections Novak produced also contained an entire page or two devoted to statistics and box scores. He took great pride in including those as part of the sports section. Leader Publications is one of very few community newspapers that still does so.

Novak was passionate about his sports coverage in every community, especially Dowagiac where he resided.

Dowagiac High School's 1990 Class BB championship football team was one of the most notable stories Novak covered, along with the Chieftains' 2011 Class B semifinalist boys basketball team. Edwardsburg's 2018 Division 4 championship football run, along with a Final Four run by Niles in softball, were other big events he covered.

Ken Fox, sports editor at the Elkhart Truth, remembers a comment Novak made in the media room following Dowagiac's 35-14 win over Oxford in that 1990 Football Final at the Pontiac Silverdome.

"I'm not sure anyone could have been happier than Scott covering that Chieftains team. We both covered Dowagiac games in the tournament, and each win made Scott's smile grow bigger," Fox recalled. "Somehow we timed it right the day of the game and ended up walking into the Pontiac Silverdome together. When he was ushered right onto the field for the game, that smile was as wide as it had ever been. His first words to the rest of the media when he came into the interview room after the win over Oxford was vintage Scott."

"I'm not sure anyone could have been happier than Scott covering that Chieftains team. We both covered Dowagiac games in the tournament, and each win made Scott's smile grow bigger," Fox recalled. "Somehow we timed it right the day of the game and ended up walking into the Pontiac Silverdome together. When he was ushered right onto the field for the game, that smile was as wide as it had ever been. His first words to the rest of the media when he came into the interview room after the win over Oxford was vintage Scott."

"I told you all back in August that Dowagiac would win it," Novak said.

Robert Oppenheim, a sportswriter at the Elkhart Truth, remembers Novak for being upbeat and positive.

"Scott certainly enjoyed his high school sports and was very knowledgeable about the area,” Oppenheim said. “Personally, he was great to me. He was one of the first people to reach out to me about a job when I was looking for one after my past job experience as a sportswriter ended. I remember having a meeting with him at a Subway in Niles talking about what the job would involve. Each week we would discuss my assignment, and he was great to work with. He understood and wasn't upset when I got a full-time sports writing opportunity at the Elkhart Truth. That's the type of person Scott was. He cared about others. Heaven got a great sportswriter and an even better person."

Brent Nate, a 1997 Dowagiac graduate now in his 14th year as the school's athletic director, grew up knowing Novak.

"I've known Scott my entire life. Looking back, I now realize how special it was to have the local sports editor there covering our middle school football games. You always knew there would be an article on the game in Saturday's newspaper," Nate said.

Nate remembers fondly the night Novak visited his home to interview his older brother after Scott Nate was selected by the Milwaukee Brewers in the 1994 Major League Baseball Amateur Draft.

"I just remember the great interest he took in getting to know our family that night. Later when I returned to Dowagiac as athletic director, we rode together to several games,” Brent Nate said. “Scott was a great advocate for high school sports, and what he did for Dowagiac athletics will never be duplicated."

The Dowagiac athletic department will have Novak's empty seat on display this winter in the exact spot where he regularly sat during home basketball games.

Edwardsburg football coach Dan Purlee remembers Novak riding the bus with the team to playoff games when Purlee coached at Cassopolis.

"I always thought very highly of Scott and got to know him really well. He just really loved the Cass and Berrien County area in terms of covering high school sports and did a tremendous job," Purlee said.

Josh Hood, Niles Brandywine's assistant principal and varsity girls basketball coach, first met Novak when Hood was a student-athlete at the school.

"Scott just loved sports, and it was more than just a job to him,” Hood said. “He was very passionate about what he did. I'll remember all the laughs we had in the Bobcat Den and just sitting around talking to him before games and all the friendly banter."

Novak was nominated by Hood as a media member to BCAM's Hall of Honor in 2022.

"It was an easy decision to nominate Scott. I was so excited that he was selected in his first time on the ballot. The articles he wrote were unbelievable," Hood said.

On the day of Novak's passing, Niles Brandywine athletic director David Sidenbender left the school's football stadium lights on overnight in his memory.

On the day of Novak's passing, Niles Brandywine athletic director David Sidenbender left the school's football stadium lights on overnight in his memory.

"I got to know Scott pretty well when I attended and played baseball at Southwestern Michigan College. He was always fair in his writing and always showed interest in other people's opinions about what he put in the paper," Sidenbender said.

"We will always feel Scott's presence. He always made our kids feel special by interviewing them after covering our games. He will be greatly missed."

Matt Brawley knew Novak both as an athlete and more recently as Niles’ athletic director.

"Scott was a staple in Southwestern Michigan sports. He was very accessible and he knew his stuff,” Brawley said. “He really enjoyed the area and covered me as a player during our District championship and Final Four runs. I also was privileged to work with him during my time at Cassopolis and Niles as AD. He was just an amazing human being, a good friend and was there for everything. You could trust him if you told him stuff off the record as well.”

Brawley set up a table in Novak's memory at last Friday's home football playoff game with Paw Paw. The table contained candles, Novak's photo and a Niles Vikings hat as a memorial to him.

"Scott was the ultimate writer who was an even better human being,” Niles varsity boys basketball coach Myles Busby said. “I can see him, even now, sitting in his chair in the corner of our gym. He had an incredibly warm and welcoming presence about him that made it easy to talk to him. I always enjoyed talking to him as a student-athlete, but I found great appreciation learning more about him during my time as head coach.”

Niles senior tailback Sam Rucker stated that Novak's presence at the games never went unnoticed.

"It means a lot to us to see the media at our games. Just having him at the games inspired us and made everyone feel good," Rucker said.

Sports weren't the only thing Novak covered for Leader Publications. He also enjoyed country and classic rock music and covered many popular artists when they appeared at area venues. He conducted interviews with Tommy James and Kenny Loggins, along with several other stars.

Outside of work, Novak enjoyed being a father to his daughter Kirsten, who survives him.

Scott Hassinger is a contributing sportswriter for Leader Publications and previously served as the sports editor for the Three Rivers Commercial-News from 1994-2022. He can be reached at [email protected] with story ideas for Berrien, Cass, St. Joseph and Branch counties.

Scott Hassinger is a contributing sportswriter for Leader Publications and previously served as the sports editor for the Three Rivers Commercial-News from 1994-2022. He can be reached at [email protected] with story ideas for Berrien, Cass, St. Joseph and Branch counties.

PHOTOS (Top) Niles High School set up a memorial table in honor of Scott Novak at Friday's home Division 4 playoff game against Paw Paw. (Middle) Novak, right, conducts a postrace interview with former professional motocross and supercross racer Mike LaRocco at the RedBud MX track in Buchanan during the Red Bud Trail Nationals several years ago. (Below) The Dowagiac High School athletic department will honor Novak by keeping his vacant chair present in the school gymnasium throughout the upcoming 2024-25 basketball season. (Top photo courtesy of the Niles athletic department. Middle photo by Amelio Rodriguez. Dowagiac photo courtesy of the school’s athletic department.)