Lessons From Banner Run Still Ring True

February 20, 2019

By Tim Miller

Mio teacher, former coach and graduate

If you were to travel to northern Michigan to canoe or fish the famous AuSable River, you might find yourself in a small town named Mio.

With one stoplight and a host of small businesses that line Main Street, Mio is well known for its access to the AuSable River and its high school sports team. And like so many small towns across America, the school is the main focal point of the community. Mio is the home of the Mio Thunderbolts, which is the mascot of the only school in town.

On Saturday, December 29, head boys basketball coach Ty McGregor and fans from around the state gathered in the Mio gymnasium to welcome back two former boys basketball teams. The two teams being honored that night were the 1989 state championship team who went undefeated and the 1978 boys basketball team who made it to the Semifinals.

As we stood there watching the former players of those teams, and coach of the 1978 team Paul Fox, make their way across the gym floor, we were reminded of the deceased players Cliff Frazho, Rob Gusler, Dave Narloch and John Byelich – the coach of the 1989 state championship team – that were no longer with us. All of them leaving us way too soon and a reminder of how fragile life can be.

The ’89 team would be a story in itself. That team was the most dominating team in Mio’s history.

After recognizing these two teams and visiting with many of them in the hallway, I stepped into the gym and began looking at the banners hanging from our walls. I found the state championship banner that the ’89 team won and the ’78 banner, and I began remembering those teams and how they brought so much excitement, happiness and pride to our small community.

Like so many schools throughout the state, the banners are a reminder of a team’s success and the year that it was accomplished. It’s a topic of conversation as former players share their memories with others about the year they earned their spot in history.

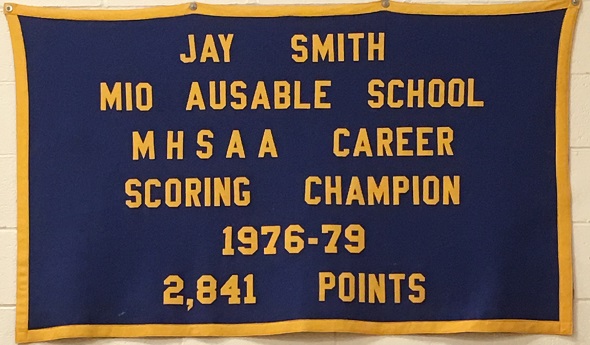

However, hanging on the south wall of the gym, all by itself, is a banner that only hangs from the walls of the Mio AuSable gym. No other school in Michigan has one like it. It has a weathered look, and the color has slightly faded over time. It’s been the conversation piece at deer camp, restaurants, and any other social gathering concerning Mio sports history. Basketball players throughout the state have dreamed of taking it away, but none have succeeded. It’s been hanging there for close to 40 years.

It reads:

Jay Smith

Mio AuSable School

MHSAA Career Scoring Champion

1976 – 1979

2,841 points

That banner represents something far greater than one person’s accomplishments. The story of how it got there and why it hasn’t left is a lesson that every sports team should learn – such a rare story in teamwork, coaching, parental support, the will to win, and the coach who masterfully engineered the plan.

The night Jay Smith broke the state scoring record, the Mio gym was packed with spectators from all parts of Michigan. The game was stopped and people rose to their feet to acknowledge the birthplace of the new record holder. After clapping and cheering for what seemed like an eternity, the ceremony was over and the game went on.

Although I wasn’t on the team, like so many people from Mio, I followed that group of basketball players from gym to gym throughout northern Michigan.

I had a front row seat in the student section where every kid who wasn’t on the team spent their time cheering for the Thunderbolts.

We were led by our conductor, “Wild Bill,” who had a knack for writing the lyrics to many of the cheers the student body used to disrupt our opponents or protest a referee’s call.

The student section was also home to the best pep band around. During home games they played a variety of tunes that kept the gym rocking. They were an integral part of the excitement that took place in that gym, game after game.

I also ate lunch and hung out at school with some of those guys. I got to hear the details of the game, the strategy, the battles between players, and the game plan for the next rival’s team.

I also ate lunch and hung out at school with some of those guys. I got to hear the details of the game, the strategy, the battles between players, and the game plan for the next rival’s team.

I remember the school spirit, the pep assemblies, and the countless hours our faithful cheerleaders put into making and decorating our halls and gym with posters.

It was like a fourth of July parade that happened every Tuesday and Friday night. The bleachers were filled with people anxiously awaiting tip off.

Showing up late meant you were stuck trying to get a glimpse of the game from the hallway.

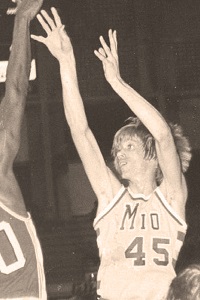

So here’s what I saw. Jay Smith was a tall, skinny kid who could shoot the ball with such accuracy that it must have been miserable for opposing coaches and players. Once it was in his hands, they had two options: watch him score or foul him and hope that he missed the free throws.

If you fouled him, you gambled wrong. He stood there and calmly shot the ball through the hoop with the sound of the net swishing as opposing players and coaches watched helplessly.

If you chose to let him shoot, you lost that bet too.

He shot often and rarely did he miss. It was no secret to our opponents or Jay’s teammates who would be doing the bulk of the shooting in Mio.

The game plan was simple: get the ball to Jay and watch him score. The Thunderbolts were coached by Paul Fox, a teacher at the school. He was demanding and intense as a coach, and his players played hard and respected him both in school and on the court. It wasn’t until I had the opportunity to coach a couple of high school teams that I realized and recognized what an incredible job he did.

I also realized what an outstanding group of players he was blessed to coach.

He was a step ahead of everybody.

Like Bill Belichick the famous coach of the New England Patriots, Paul Fox understood how to build a team around one person. He convinced everyone on the team that the way to the promised land was through the scoring of Jay. However, the type of players who buy into such a plan have to be special. And they were. Jay was blessed his first two years on varsity. He was surrounded by a very talented group of ball players who allowed him to be successful.

His last two teams weren’t as talented, but just as special.

Most of those guys were classmates of mine, so here’s what I can tell you.

Not one time during that stretch did I ever hear one of them complain about playing time. There was no pouting on the bench or kicking it because you were taken out.

No one complained the next day about their stats. They were happy to win, and if that meant Jay shooting most of the time, that was okay with them. After the game, no one ran to the scorer’s table to check their stats. Or went off in the corner of the locker room to act like a preschooler in timeout. Their parents didn’t march over to the coach and demand answers on why their son wasn’t playing or shooting more. Players didn’t quit the team because their individual needs weren’t being met. There were expectations from the coach, the parents, and everyone else involved. After each home game, the whole community gathered at the local bar/ bowling alley. Players, parents, and fans were happy their team had won and celebrated together in the victory. It was a simple blueprint that every sports team should follow.

Forget about your own personal gratification and do what’s best for the team.

It’s a lost concept these days. And the question many of us in Mio talk about from time to time is will the record ever be broken?

There’s more than one factor to consider when discussing the topic.

Jay set that record long before the 3-point shot was implemented.

Can a coach like Paul Fox assemble a group of players who would put their ego aside and desire winning more than their own personal satisfaction?

Can you find a humble kid like Jay who would crush the dreams of opposing teams with his shooting ability?

Can you find a group of parents out there willing to watch a kid like him put on a show, game after game, and not be offended?

Can you find a student body like the one we had to fill the student section with loud, rowdy fans?

Can you find a student body like the one we had to fill the student section with loud, rowdy fans?

The scoring banner represents the scoring accomplishments of Jay. And to his credit, I never once heard him brag about his success on the court.

He simply said, “We won.”

But that banner represents more than points. It’s an amazing story of what happens when a group of people come together with a common cause – the will to win.

What we saw during that time was special!

The state scoring record was set by Jay and a large list of supporting teammates who helped him.

He was fortunate to have a coach who understood how to manage and convince a group of players to buy into his system.

A group of parents who understood what was going on and supported it.

A student body section that rattled the best players from the other teams game after game.

A dedicated group of cheerleaders who spent countless hours making posters to decorate our school with pride.

A pep band that brought their best sound, game after game.

A teaching staff who understood how a bunch of kids wanted to get ready for the next big game, and gave us their blessing.

It was the culture of our school and community. Get ready for the game.

The anticipation, those long lines waiting outside in the cold, those packed gyms, that noise.

It was all part of it.

Perhaps somewhere in Michigan a group of coaches, players, parents, teachers, and fans could copy the formula from the ’70s that brought our team, school, and town so much success.

If a coach can find a group of players that only care about one thing, and that’s winning, it can be done. Doing that will require a group of people who think they understand the concept to execute it. As a society we see it at every level of sports: the “I” syndrome, the selfishness, the lack of respect for coaches and teammates. It’s the fiber that destroys any chance for success.

My guess is the banner will hang in our gym until someone in the school decides to replace the old one. Perhaps Jay’s children or grandchildren will want the old one to add to their family memorabilia. And after the new one is hung up and another forty years have passed, someone else will write a story about the banner that continues to hang in Mio’s gym.

NOTE: Jay Smith went on to play at Bowling Green and Saginaw Valley State University, and coach at Kent State, University of Michigan, Grand Valley State, Central Michigan, Detroit Mercy, and currently as head coach at Kalamazoo College. He was diagnosed with prostate cancer last summer and faces another round of radiation treatments after undergoing surgery in September. Click for a recent report by WOOD TV.

PHOTOS: (Top) The banner celebrating Jay Smith’s state high school career scoring record continues to greet fans at Mio High School’s gym. (Middle) Smith was a standout for the Thunderbolts through his graduation in 1979. (Below) Smith scored 2,841 points over four seasons, averaging 29 points per game.

Performance of the Week: Ishpeming Westwood's Ethan Marta

December 18, 2025

Ethan Marta ♦ Ishpeming Westwood

Ethan Marta ♦ Ishpeming Westwood

Senior ♦ Basketball

The 6-foot-3 guard averaged 27 points per game as a junior in leading Ishpeming Westwood to the Division 3 Semifinals, and he scored 18 points with 13 rebounds and four assists as the Patriots came back last week from 17 points down to defeat Kingsford 59-54. The Flivvers also had reached Breslin last season, in Division 2.

Westwood sits 6-0 heading into Friday’s game against Negaunee, and finished 22-6 last winter – when the Patriots lost their early-season matchup with Kingsford, 57-50. Westwood’s trip to the Semifinals in March was its first since 2003. Marta also played football and will play baseball this spring, and has signed to play college basketball at Michigan Tech.

@mhsaasports 🏀POW: Ethan Marta #ishpemingwestwood #basketball #highschoolsports #performanceoftheweek #MHSAA ♬ Bright and fun upbeat pops, Kids, Animals, Pets, Fun, Cute, Happy, Playful, Upbeat(1465232) - SAKUMAMATATA

@mhsaasports 🏀POW: Ethan Marta #funfacts #tiktalk #performanceoftheweek #highschoolsports #MHSAA ♬ Girly and cute synth pop - SAKUMAMATATA

Follow the MHSAA on TikTok.

MHSAA.com's "Performance of the Week" features are powered by MI Student Aid, a division within the Department of Lifelong Education, Advancement, and Potential (MiLEAP). MI Student Aid encourages students to pursue postsecondary education by providing access to student financial resources and information. MI Student Aid administers the state’s 529 college savings programs (MET/MESP), as well as scholarship and grant programs that help make college Accessible, Affordable and Attainable for you. Connect with MI Student Aid at www.michigan.gov/mistudentaid and find more information on Facebook and X @mistudentaid.

Previous 2025-26 honorees

Dec. 11: Louis Smith, Three Rivers wrestling - Report

Dec. 4: Traverse Smith, DeWitt football - Report

Nov. 28: Elizabeth Eichbrecht, West Bloomfield swimming - Report

Nov. 20: Brady Kieff, Blanchard Montabella football - Report

Nov. 13: Ella Laupp, Battle Creek Harper Creek swimming - Report

Nov. 7: Hunter Eaton, Charlevoix cross country - Report

Oct. 31: Stephen Gollapalli, Lansing Christian tennis - Report

Oct. 23: Talya Schreiber, Pickford cross country - Report

Oct. 16: Avery Manning, Dexter golf - Report

Oct. 9: Brady Van Laecke, Hudsonville football - Report

Oct. 2: Sarah Giroux, Flat Rock volleyball - Report

Sept. 25: Sam Schumacher, Portage Central tennis - Report

Sept. 18: Kaylee Mitzel, Saline field hockey - Report

Sept. 11: Natasza Dudek, Ann Arbor Pioneer cross country - Report

Sept. 4: Kate Posey, Big Rapids golf - Report

(Action photo by Cara Kamps. Headshot courtesy of J Birdie Photography.)