Howell Names Field for Longtime Leader

August 30, 2018

By Tim Robinson

Special for Second Half

If you got the impression that John Dukes has been around Howell football forever, you wouldn’t be far off.

His association with the program began before high school.

His association with the program began before high school.

“When I was a kid, I used to live near Page Field (Howell’s former athletic complex), and I would go out and watch football practice,” Dukes said. “I was at practice all the time, and the coach said, ‘If you’re going to be here all the time, you may as well get some water for the boys while they’re practicing.’”

That was in 1963, when the Highlanders went 9-0.

A little more than 55 years later, Dukes will be honored tonight when the field at Howell’s Memorial Stadium will be named John Dukes Field.

Howell football coach Aaron Metz began the drive to name the field after Dukes when it was determined the old turf, installed in 2004, needed to be replaced.

“We have a commitment award named for John,” he said. “If you play football for four years, you get the John Dukes Commitment Award. We put a committee together with people who have been around Howell for a long time, and when you ask anybody, they say there’s not a person more deserving than John Dukes.

“So I ran it up the ladder to the athletic director and superintendent, and, to be honest, it was a pretty easy process because no one could find anything bad about John,” Metz added. “We’re excited to have the opportunity to do it.”

Dukes was a three-year varsity player at Howell and then played at Alma College, where his teams won three league championships.

With the exception of six years at Hartland coaching under his son, Marcus, John Dukes has been affiliated with Howell football for 46 years, including 25 as the head coach.

After graduating from Alma in 1972, Dukes got a teaching job at Howell and was an assistant freshman coach for a season and a varsity assistant for two before taking over as head coach at age 25.

“My philosophy at the time was I wanted to help the kids enjoy playing football and help them to be successful at it,” he recalled. “The previous three years our record wasn’t very good. That was one of my objectives, was to make it fun.”

He then talked about his first season with a little self-deprecation, a common thread in most conversations with Dukes.

“I remember my first game,” he said. “Because I played defense in college (Dukes was a linebacker), I thought we were going to be a really good defensive team. We played Fenton in my first game, and we lost 32-19, so my defensive prowess wasn’t good at the time.”

The Highlanders lost six of their first seven games that season, but won the last two and went 8-1 three seasons later.

In all, Howell had winning records in 15 of his 25 seasons, but one group of players stood out for an entirely different reason.

“We had a period of time (1989 and 1990) where we weren’t very good, and we lost 17 games in a row,” he said. “But those kids were wonderful kids to coach. They came to practice with energy all the time, and from a coaching standpoint, it was wonderful to coach them during the week. Now, Fridays were a different story, because we didn’t play very well on Fridays, ever.

“But the real thing that stands out with that group was the very last game of their senior year we beat (Waterford Kettering), and you’d have thought we’d won the Super Bowl,” Dukes continued. “Those kids who were seniors, that was their first football victory in high school. It was an amazing time. We had several teams with good players, and I really enjoyed coaching them, too, and I don’t want to leave them out. But that really stood out in my mind, in that they came out to work every day.

“But the real thing that stands out with that group was the very last game of their senior year we beat (Waterford Kettering), and you’d have thought we’d won the Super Bowl,” Dukes continued. “Those kids who were seniors, that was their first football victory in high school. It was an amazing time. We had several teams with good players, and I really enjoyed coaching them, too, and I don’t want to leave them out. But that really stood out in my mind, in that they came out to work every day.

“Over a period of time of losing that many games, sometimes, it’s not fun and it’s not fun for them or the coaches. But we had a very enjoyable time over that two-year period, regardless of the fact we didn’t win any games.”

His perspective is consistent with the principles by which he ran his program.

“These weren’t original to me,” he says, “but the three things I always told our kids was your faith should be your number one priority, your family should be your number two priority. Football, when school hadn’t started, should be number three. And when school started, school became three and football became number four. We tried to base everything we did on these priorities in our lives. Sometimes those things cross over and mix and match. When they do, then you have to step back and say what is really important here?”

Dukes resigned after the 1999 season.

“There were a lot of things and I don’t know if anything in particular,” he said of his decision. “I had been doing it for 25 years, and we had a string of years where we were 6-3. So we were OK, but I felt it was time to be done with it.”

His self-imposed exile lasted one season. He had a couple of stints as an assistant coach when he finally decided to retire for good in 2006.

“No sooner had I done that, my son (Marcus) called me up and said he just got the Hartland job,” Dukes recalled. “He said, ‘Dad, you have to come here and help.’ So I went there for six years. Then he resigned, and I thought I was going to be done again.”

After another stint as a Howell assistant, John Dukes took the last two years off before agreeing to rejoin the program as a junior varsity assistant this season, as the offensive coordinator.

As it turns out, one grandson, Jackson Dukes, plays on the Howell JV, and John Dukes also is helping coach another grandson, Colin Lassey, on his junior football team.

“When Jackson gets home, I ask him, ‘Did you get yelled at by Grandpa today?” Josh Dukes says. “And when he says yes, I say, ‘Good. You should be getting yelled at.’ So nothing has changed in the 30 years since high school.”

Josh Dukes, the oldest of John Dukes’ three children, joined Marcus in playing football for their father.

“There was never an expectation that we had to be this or that,” Josh Dukes said of himself, his brother and sister, Carrie. “Now maybe he was a little harder on me, but that’s something we were thankful for. I’d rather him be harder on me than any kid on the field, because then the other kids left me alone. They knew it was the same for everyone across the board. He wasn’t going to take it easy on me, my brother or my sister.”

John Dukes coached his daughter, Carrie, when she played middle school basketball.

“The first time he coached me, he came home to my mom and said, ‘I don’t know how people do this,’” she recalled. “‘They’re all crying, half of them don’t think I like them. I don’t know how to do this with girls. It’s a totally different ballgame.’ But he was a great coach. I know some people don’t like their parents coaching them, but I loved having him coach.”

Like her brothers, Carrie Lassey stayed involved with sports. She is now the athletic director at St. Joseph Catholic School in Howell.

“He coached my freshman team a couple of years ago,” she said. “It was third and fourth-grade girls. It’s amazing. He can coach pretty much anybody.”

Indeed, Dukes also coached baseball and wrestling at the varsity level at Howell, and, for a couple of weeks, filled in as a competitive cheer coach when the Highlanders had a temporary vacancy.

“I was more a supervisor,” he said, but serving that role illustrated his commitment to the athletic program as a whole. He was needed, and he stepped in.

Having stopped and started his career so many times, Dukes, now 68, laughs when asked about what he will do when he retires in the distant future.

Having stopped and started his career so many times, Dukes, now 68, laughs when asked about what he will do when he retires in the distant future.

“I’m sure he’ll be coaching when he’s in his 90s. Maybe triple digits,” jokes Bill Murray, the former Brighton coach who matched up with Dukes’ teams during the second half of Dukes’ Howell tenure. “The guy loves the game, he’s out there and he has a lot to offer. His teams were always well-prepared, they played great defense, were fundamentally sound and when you went nose-to-nose, they were consistent as to what they were going to do. It was a matter of whether you could stop them or not.”

Dukes still keeps up with the Howell varsity, still offers advice when asked, and still enjoys the competition.

“For me, as a head coach, it’s great having a coach (on staff) who has been there and done it to talk to and mentor, even me,” Metz said. “What makes a successful coach, I don’t think, changes, whether it’s been 50 or 100 years ago to the current day. He steered the ship to have an outstanding record (130-95) and also have a huge impact on kids in our community.”

“When people talk to me about my dad, they say he was a dad to them, or like a second dad,” Josh Dukes added. “Or, ‘I wanted to be a teacher because of him.’ These are the things that for us,” referring to his siblings, “is the most impressive part. The kids of players he’s coached, or the grandkids.”

Dukes has the unusual distinction of having coached more congressmen (Mike Rogers and Mark Schauer, who started on the offensive line for Dukes in the late 1970s) than pro football players (Jon Mack, who played for the Michigan Panthers of the USFL in 1984).

John Dukes will give a short speech before tonight’s ceremony, which will take place before Howell’s home opener against Plymouth.

“They’ve given me five minutes, but it will probably be shorter because they want to get the game started on time,” he joked.

“It’s an incredible honor,” Josh Dukes said. “Everyone in our family feels the same way. I don’t think he ever went into this with any intentions of being singled out. It’s a great lesson for our community and our athletes, to see what hard work and effort and care for your community can do, you know?”

During the ceremony, the letters “John Dukes Field,” which were sewn into the artificial turf in Howell’s Vegas Gold, will be unveiled.

“Aaron showed it to me last week when they were putting it in,” John Dukes said, then joked, “I thought (the lettering) was going to be a little trademark sign (sized), and my goodness, it’s bigger than the numbers. It’s a little bit ostentatious for me, I think; wow, that’s quite a tribute. I’m very humbled by it and honored by it and very appreciative of what people have done to make this happen.”

A few days later, Dukes posed for a picture next to his name on the field and chatted with a reporter as they left the stadium.

Then, he turned a corner to the JV football office and kept walking.

Before he became a living legend, John Dukes was a football coach, and there’s a game coming up and his team to prepare.

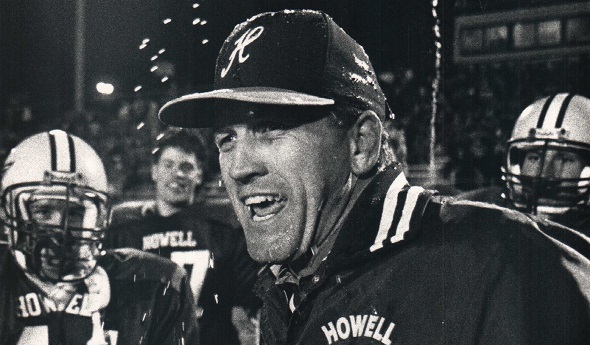

PHOTOS: (Top) Howell coach John Dukes celebrates his team’s 38-0 playoff victory over Wayne Memorial in 1992. (Middle) Dukes, during the 1991 season. (Below) Dukes stands next to the lettering that will be unveiled Thursday when the school’s field is named in his honor. (Photos taken or collected by Tim Robinson.)

Finals Flashback: Remembering the '9s'

November 29, 2019

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

This weekend’s MHSAA 11-Player Football Finals at Ford Field will conclude another decade for the most played and watched high school sport in Michigan.

We’ll roll into this year’s games remembering some decade-enders of the past from 1979, 1989, 1999 and 2009.

Redemption

The 1979 season marked the first playoff appearance for Norway, which had failed to qualify for the MHSAA postseason in 1975 and 1976 despite undefeated seasons.

However, the scoreless first half of the Knights’ Class D championship battle with Schoolcraft wasn’t proceeding as planned.

“We went into the locker room at halftime and made a few offensive changes,” said Norway coach Bob Giannunzio. “Our running game wasn’t working, so we decided we would pass more in the second half.”

The Norway defense forced six second-half turnovers that led to three touchdowns and a 21-6 win over Schoolcraft. Quarterback Chuck Soderlund connected on 6-of-14 passes for 110 yards including a 45-yard TD pass to Gregg Noordhoff to break the scoreless deadlock. Nordhoff added a second score from four yards out early in the in the fourth quarter for a 14-6 lead. Soderlund added a game-sealing TD on a QB sneak with 1:30 remaining.

It was the first of back-to-back titles for Giannunzio and the little Upper Peninsula school located near Iron Mountain. Since that season, Norway has advanced as far as the Semifinal round twice, in both 2002 and 2006

“We said if we ever got here we’d win it, said Giannunzio to the Detroit Free Press. “We wanted to start off right for the U.P. It’s a big burden playing for the whole Upper Peninsula.”

The Greatest

In Class B in 1989, Farmington Hills Harrison scored a 28-27 victory over DeWitt in what many still consider one of the greatest games of the MHSAA’s 45-year playoff history. The reigning Class B champion and top-ranked Hawks had their hands full. Tied 7-7 after one quarter, the Panthers grabbed a two-touchdown lead in the second quarter on 32-yard run by fullback John Tellford and a 35-yard pass play from Tellford to John Cowan. Harrison responded with a Matt Conley one-yard run to cut the margin to 21-14 at the half.

Hawks quarterback Mill Coleman knotted the score at 21-21 with a dazzling 16-yard run early in the fourth quarter, but DeWitt stormed back again driving 75 yards on 13 plays. The series was highlighted by tight end Dave Riker's 24-yard, one-handed catch to the Hawks’ 3-yard line. Two plays later, quarterback Chris Berkimer slipped over from the 1, and DeWitt again took the lead 27-21.

With 2:12 remaining and the ball at the Harrison 33, Coleman went to work. Three quick completions moved the ball to the DeWitt 16, and then Coleman let his legs do the rest. Following a Hawks timeout, Coleman dashed right for seven more yards to the Panthers’ 9. Facing a 2nd-and-3, Coleman dropped back to pass, escaped the rush at the DeWitt 17, then scampered up the middle and dove into the end zone for the tying points. Steve Hill added his fourth PAT of the game with 1:34 remaining for the final margin, then secured the victory with an interception on the next series.

Electrifying

Charles Rogers, perhaps the most electrifying high school receiver to ever touch the carpet at the Pontiac Silverdome, caught a single pass in the 1999 Division 2 title game, but he was the difference maker in Saginaw’s 14-7 win over Birmingham Brother Rice. The reception, defended by a single back, was a 60-yard touchdown reception from Brandon Cork on Saginaw’s first possession. Rogers broke a pair of tackles on the way to the end zone to open the scoring. The point-after attempt was blocked.

It was one of only six pass attempts by Saginaw on the day, and the only completion. But after that, as Mick McCabe of the Detroit Free Press wrote, “If Rogers would have gone up to the concourse for a hot dog, I’m sure a couple of Rice defensive backs would have been there to wipe the mustard off his chin.”

“He’s a big-time player, he should be in the NFL,” Rice coach Al Fracassa told McCabe. “He reminded me of Randy Moss. He’s always a threat just having him out there.”

A Saginaw fumble on the first play of the second half was recovered by Rice’s Tony Gioutsos at the Trojans’ 31. Eight plays later, Gioutsos scored from five yards out. Ross Ryan added the extra point for a 7-6 Rice lead.

Saginaw’s defense was aggressive, with constant pressure on Rice quarterback Mark Baker, sacking him twice while holding the Warriors to 78 yards rushing on 36 attempts.

Saginaw took advantage of the extra attention received by Rogers. Terry Jackson pounded out 106 yards on 18 carries, including 60 of Saginaw’s 84 yards on their game-winning drive in the fourth quarter. With Rogers drawing triple coverage, Jackson dashed opposite side for a 17-yard TD with 7:03 to play. Jackson also added the 2-point conversion for the game’s final margin.

A Wild Ride

Farmington Hills Harrison picked up its 10th state title with a 42-35 win over Grand Rapids Creston in a 1999 Division 3 championship game filled with wide-open play. Creston opened the title contest with a recovered onside kick and then drove 49 yards in five plays, ending with an Andrew Terry’s touchdown from a yard out. Harrison rebounded with a field goal, followed by a three-yard TD run by Kevin Woods off a pass interception for a 10-7 lead.

Creston responded with a four play, 79-yard touchdown drive that consumed a little over two minutes. Featuring a 41-yard pass play from QB Carlton Brewster to Lanard Latham near the end of the first quarter, the Polar Bears opened the second with a 25-yard run to the end zone by Terry. Odene Pringle’s extra point gave Creston a 14-10 lead.

Harrison then went 68 yards in six plays and under three minutes as Woods scored again from a yard out to regain the lead for his team 17-14.

The fireworks continued following another pass interception by the Hawks and another three-yard TD by Woods that upped the lead to 24-14. By halftime it was 27-21.

Harrison’s lead was short-lived as coach Charles “Sparky” McEwen’s Creston squad went 80 yards in 2:27 following the kickoff, capped by a Brewster to Latham 11-yard scoring strike. Pringle’s kick made it 28-27.

The Hawks responded on the next drive. It was 35-28 at the end for three quarters, then 42-28 when Woods scored again near the beginning of the fourth. In total, he would finish with 153 yards on 33 carries and four touchdowns, tying then-Final scoring marks for touchdowns and points.

Creston struck again with a 56-yard touchdown pass to Richard Gill from Brewster with 7:00 remaining to pull within a seven, 42-35. The Polar Bears regained the ball with 57 second remaining, but a final Hail Mary fell incomplete, ending one of the tournament’s most entertaining games.

Thriller

In 2007, the East Grand Rapids-Orchard Lake St. Mary’s championship battle was a 5 OT affair.

In 2009, it was again anybody’s guess who would emerge as the winner between the schools. The Pioneers entered undefeated, while Orchard Lake St. Mary’s carried four losses into the contest. They began the year with two defeats for the first time since 1991. The first was to this same East team, 21-7. Two others were to Division 1 Detroit Catholic Central, 27-0 and then 7-0.

The opening quarter of the Division 3 Final was scoreless. Orchard Lake opened the scoring early in the second. Quarterback Robert Bolden hit Gary Hunter for a 49-yard completion, and three plays later Bolden broke a pair of tackles to ramble across the goal line from 13 yards out. The Pioneers tied the game at 7-7 with 30 seconds remaining before the intermission, when 6-foot-7 Colin Voss caught a five-yard pass from Ryan Elble and snaked the last two yards into the end zone. St. Mary’s nearly answered in the time remaining as Hunter returned the kickoff 63 yards to the Pioneers’ 24. A false start penalty sent the ball back to the EGR 29, but then Bolden completed a pass to Allen Robinson for 28 yards to the Pioneers’ 1-yard line. Two rushing attempts by St. Mary’s were stopped at the goal line as time expired in the half, the last by Bolden that was ended by East’s Joshua Laarman.

Orchard Lake had opened a 21-17 lead with 9:12 remaining in the game following a three-yard TD by Cortez Riley and an extra point by Nathan Perry. With 4:01 left, that score still stood as the Pioneers took possession at their own 13 following an Eaglets punt. Kirk Spencer dashed for 38 yards to the Orchard Lake 49 on the first play. But with 2:49 remaining, East faced desperation at 4th-and-14. The ensuing pass, intended for Voss, slipped off his fingertips, but was caught by Spencer for a gain of 27 yards to the St. Mary’s 26. With 1:14 to play, Elble found Deon Jobe in the end zone from 15 yards out. Bobby Aardema’s kick gave East Grand Rapids a 24-21 lead.

“But it wasn’t quite over until we heard from Laarman and Spencer one more time,” wrote McCabe about play after the touchdown. “Bolden completed two passes to get to East’s 44 when he took off running. Earlier he scored on a breathtaking 83-yard keeper (giving St. Mary as 14-10 lead in the third quarter).

“The first thing Laarman thought of when he saw Bolden take off was: here we go again.”

Laarman caused a fumble on his attempted stop, and Spencer came up with the ball to seal victory. The win gave East Grand Rapids its fourth consecutive championship. East Grand Rapids would win five straight Division 3 titles between 2006 and 2010.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTO: Farmington Hills Harrison scored late to edge DeWitt 28-27 in the 1989 Class B Final. (Photo courtesy of the Lansing State Journal.)