Century of School Sports: Predecessors Laid Foundation for MHSAA's Formation

By

Geoff Kimmerly

MHSAA.com senior editor

January 14, 2025

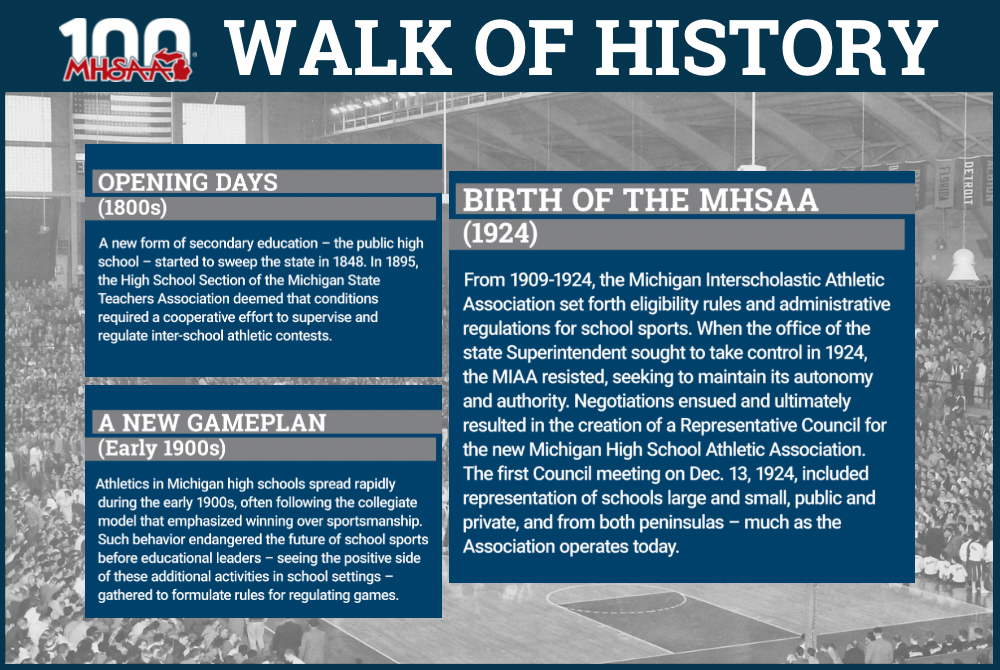

We have celebrated throughout this school year the 100th anniversary of the Michigan High School Athletic Association – our “Century of School Sports.” But the first high school sports in this state were being played more than a half-century before the MHSAA was established in December 1924 – and it’s important to recognize our predecessor organizations for their pioneering work.

To keep things very brief, it’s fair to say that high school athletics in Michigan followed the increase in number high schools across the state – especially public schools – as well as interest in sports predominantly at the college level.

In lieu of citing detail by detail, the following is based on research from “Athletics in Michigan High Schools – The First Hundred Years” by L.L. Forsythe, who served as the first president of the MHSAA Representative Council after playing a leading role in its creation as an officer of the previous Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Association. Newspaper reports of the day also contributed to what's summarized below.

It is also key to keep in mind a few things about the organizations that regulated high school athletics before the MHSAA, and to understand their relation to our work today:

- Schools at the start of organized athletics sought primarily to create competitive equity and a safe playing environment for their teams and athletes.

- Schools looked to the statewide organization to uphold and consider appeals for those rules regulating eligibility and fair play.

- Schools later asked for the statewide organization to take over sponsorship of the statewide championship events that began to crop up over the 30 years before the MHSAA formed.

According to Forsythe’s research, the first public high schools in Michigan opened during the middle of the 19th century – as of 1850, only 3-4 existed, but after the Civil War that number began to grow, and with it an interest in athletics as part of student life. Football and baseball were main draws, later to be joined by basketball and track & field – which would be among the MHSAA’s first championship offerings several years later.

The Beginning (1895-1909)

Forsythe notes that 1895 saw the first steps toward regulating high school athletics on a statewide basis. A few entities took on roles in an attempt to bring structure.

- The Michigan State Teachers Association, which in 1895 began to recruit schools to become part of an organization that would require eligible athletes to be enrolled students, succeeding academically with at least a “passing grade,” and participating in no more than five seasons or years of a sport. However, the MSTA did not have a program of activities, as those of the day were generally organized by universities.

- The University Athletic Association was formed by University of Michigan in 1898, and was the main organizer of invitational “state” championships in partnership with the MSTA.

- Another organization, the Michigan Inter-School Athletic Association, also pops up in 1895 as the host of what aspired to be an annual field day.

Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Association (1909-1924)

The Michigan Schoolmasters’ Club absorbed control of athletics from the MSTA in April 1909, forming the MIAA and immediately introducing a series of regulations including an age limit of 21 years old, an eligibility limit of four years, and a restriction on participation by athletes who had competed professionally.

The MIAA would continue to set other eligibility rules, charge dues ($1), and also write into bylaws that member schools could play only member schools. That latter detail was a big driver of growth – the revised MIAA constitution in 1921 added that regulation, and the association grow from 26 schools in 1920 to 130 in 1921, to 284 in 1922 to 305 schools in 1923.

On the event side, the MIAA conducted its first state track meet in 1912, then did so coordinating with Michigan State College. The 1921 basketball tournament saw the first mention of classes – Class B for schools with 250 or fewer students, and Class A for schools with more than 250.

It should also be noted that during the early 1920s, MIAA representatives helped form the organization (first of Midwest states) that would become the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) – which continues to write game rules for nearly all MHSAA sports.

The MIAA continued operating into its annual meeting in December 1923, when leaders were presented with an unwelcome surprise announcement – the Michigan legislature, at the close of its recent session, had transferred supervision of interscholastic athletics to the state Superintendent of Public Instruction (to the superintendent's surprise as well, Forsythe noted).

The negotiations between schools and the state over the following year resulted in the dissolution of the MIAA on Dec. 5, 1924 – and the first meeting of the MHSAA eight days later.

Previous "Century of School Sports" Spotlights

Jan. 9: MHSAA Blazes Trail Into Cyberspace - Read

Dec. 31: State's Storytellers Share Winter Memories - Read

Dec. 17: MHSAA Over Time - Read

Dec. 10: On This Day, December 13, We Will Celebrate - Read

Dec. 3: MHSAA Work Guided by Representative Council - Read

Nov. 26: Finals Provide Future Pros Early Ford Field Glory - Read

Nov. 19: Connection at Heart of Coaches Advancement Program - Read

Nov. 12: Good Sports are Winners Then, Now & Always - Read

Nov. 5: MHSAA's Home Sweet Home - Read

Oct. 29: MHSAA Summits Draw Thousands to Promote Sportsmanship - Read

Oct. 23: Cross Country Finals Among MHSAA's Longest Running - Read

Oct. 15: State's Storytellers Share Fall Memories - Read

Oct. 8: Guided by 4 S's of Educational Athletics - Read

Oct. 1: Michigan Sends 10 to National Hall of Fame - Read

Sept. 25: MHSAA Record Books Filled with 1000s of Achievements - Read

Sept. 18: Why Does the MHSAA Have These Rules? - Read

Sept. 10: Special Medals, Patches to Commemorate Special Year - Read

Sept. 4: Fall to Finish with 50th Football Championships - Read

Aug. 28: Let the Celebration Begin - Read

Specialization Not the Only Pathway

April 21, 2015

By Eric Martin

By Eric Martin

MSU Institute for the Study of Youth Sports

Specialization is not a new topic facing athletes and parents.

In a 1989 study by Hill and Simons, athletic directors indicated that the three-sport athletes of the past were being replaced by athletes who only participated in a single sport. Multiple athletic directors indicated that the decrease of multi-sport participation was a concern for all involved in the sport environment as increased emphasis on sport specialization was not in the true vision of high school sports.

Even though the distress concerning sport specialization is not a new topic, the rise of club sports and year-round travel teams have increased the number of youth athletes who are forced to make a choice between playing multiple sports or focusing their time and training efforts solely on one sport. The decision to focus solely on one sport sometimes is done by athletes (or their parents) who believe that quitting other sports is the sole way to earn a coveted college scholarship.

However, even though counter intuitive, sport specialization may be hampering their pursuit to play at the next level.

Elite level achievement in sport is rare, with statistics showing that only 0.12 percent of high school athletes in basketball and football eventually reach the professional level. To combat these odds, many in popular media including Malcolm Gladwell have forwarded Anders Ericcson’s proposal that to become an expert in a field, an individual must accumulate 10,000 hours of practice.

To achieve this aim, many parents and athletes disregard other sports believing that extra exposure to a single sport may result in accumulating these hours quicker and increase an athlete's chances of elite skill achievement. Reducing the achievement of sport excellence to solely practice hours overlooks the importance that developmental, psychosocial, and motivational factors play in the achievement of high level success in youth. Further, several research studies have found that elite athletes typically fall short of this 10,000 hour milestone.

Simply accumulating a magic number of hours does not guarantee sport success, and in fact, trying to accumulate these hours too early can lead to many different negative outcomes for youth.

Sport specialization has been shown to have a variety of negative physiological and psychological outcomes for youth athletes. Typically, athletes who specialize in one sport play that sport year-round with little or no offseason. In these cases, athletes who continually perform repetitive motions such as throwing or jumping can experience overuse injuries that can range from tendinitis to torn ligaments.

In addition to the increased risk of injury, youth who specialize and play a single sport year-round are at risk for psychological issues as well. Youth who play a single sport are less likely to allow for proper recovery and face the increased chance of burnout or decreases in motivation that may result in leaving sport entirely. Additionally, as practice time demands and multiple league involvement increases, youth may feel added pressure to succeed due to the increased time and financial costs incurred by parents.

Finally, youth who specialize early in only one sport do not develop the fundamental motor skills that help them stay active as adults, instead only developing a very narrow skill set of a single sport.

If the dangers of sport specialization do not encourage multisport participation, a majority of studies have shown that sport specialization does not increase long-term sport achievement. In fact, most studies indicate that athletes who reach the highest level of sport achievement typically played a variety of sports until after they were well into high school.

For example, a study with British athletes found that youth who played three or more sports at the ages of 11, 13, and 15 had a significantly higher likelihood of playing on a national team at ages 16 and 18. These athletes had a more rounded set of skills, were more refreshed for their chosen sport, and were more psychologically and emotionally ready to perform due to their experiences in a number of sports.

A study recently conducted by the Institute for the Study of Youth Sports with collegiate athletes showed similar results as the British athlete study. In the ISYS study, 1,036 athletes from three Division I universities were asked to report their past youth sport participation. On average, youth participated in three or more sports in elementary and middle school. The number of sports youth participated in decreased with each year of high school, but even with the decrease of participation, a larger number of individuals played more than one sport during every year of high school including senior year than those who played a single sport.

Even though a majority of athletes did play at least two sports throughout high school, several athletes did indicate that they specialized in one sport indicating that there are multiple pathways to elite sport achievement.

Athletes were also asked for their perception of how important it was to specialize in one sport in order to earn a college scholarship. On a scale of 1-9, athletes felt that specializing in one sport prior to high school was neither important nor unimportant (4.97).

Sport specialization is not a new issue, but that does not minimize the damage that can occur if athletes are overtaxed early in their development. Each athlete is unique, and each situation requires care. If an athlete does decide to play in only one sport, the decision should be made in regards to the athlete’s interest and development, not just in the pursuit of a college scholarship. Additionally, if athletes specialize in one sport, it is critical to understand that youth are developing and proper recovery is critical both physically and psychologically.

Early specialization in sport is an issue that is not going to go away, but for coaches, parents, and athletes this decision should be made with a long-term perspective and with the athletes’ long-term well-being central to the choice.

Martin is a fourth-year doctoral candidate in the Institute for the Study of Youth Sports at Michigan State University. His research interests include athlete motivation and development of passion in youth, sport specialization, and coaches’ perspectives on working with the millennial athlete. He has led many sessions of the MHSAA Captains Leadership Clinic and consulted with junior high, high school, and collegiate athletes. If you have questions or comments, contact him at [email protected].